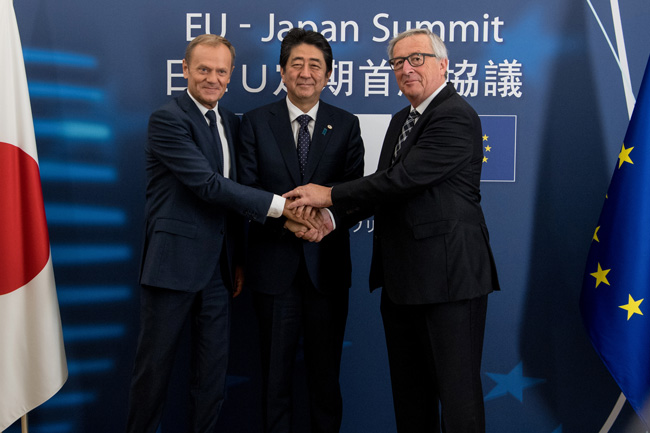

Donald Tusk (left), president of the European Council; Shinzo Abe, prime minister of Japan; and Jean-Claude Juncker, president of the European Commission, at July’s EU–Japan Summit.

In early July, the BBC reported that the European Union (EU) and Japan had formally agreed an outline of a free-trade deal. The agreement paves the way for trading in goods without tariff barriers between two of the world’s biggest economies. The BBC website gives no detailed information, but suggests that a full and workable agreement may yet take time to implement. Indeed, some suggest that transition clauses may last as long as 15 years.

What is clear, however, is that the most important sectors to be affected are Japanese automobiles going to Europe, and EU agricultural produce entering Japan. The bilateral negotiations began in 2012, but soon broke down. According to the BBC’s Damian Grammaticas, the election of Donald Trump and an increasingly inward-looking America encouraged the EU and Japan to put aside their differences and demonstrate to their domestic audiences that they are capable of promising new economic opportunities.

The potential agreement came after a meeting in Brussels between Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and President of the European Commission Jean-Claude Juncker. Some will see this as limited compensation for the collapse of the oft-touted Trans-Pacific Partnership (TTP), which US President Donald Trump scrapped in January. By contrast, the president of the European Council said that the agreement showed the EU’s commitment to world trade.

Meanwhile, the Financial Times reports that Norio Maruyama, a Japanese government spokesman, told an audience in Brussels that the trade deal had been agreed on the basis that it was with all 28 EU member countries. He said it was still “too hypothetical” to say whether any adjustments would need to be made after the UK leaves the EU, noting that, “we cannot predict at this stage what is the real effect of Brexit” on the accord.

Across the channel

So where, exactly, does that leave the UK?

For now, Japan has significant investments in the UK, and automobiles and automotive parts feature strongly. Equally, Britain’s exports to Japan remain strong, with special chemicals and automotive parts high on the list. London remains an important centre for Japan’s financial institutions, though some are reportedly looking at alternative, post-Brexit European locations. For example, Daiwa Securities Group Inc. recently announced it would be opening a subsidiary in Frankfurt, and Nomura Holdings Inc.—Japan’s biggest brokerage—has also announced it will make the German city its post-Brexit base.

Abe is keen to start informal talks on free trade before Britain leaves the EU as, according to The Guardian, he is anxious to soften the expected blow to Japanese firms headquartered in the UK. But under EU rules, formal negotiations cannot begin until after Britain last left.

Abe is reported to be concerned about Brexit because of the widely held perception that it will negatively affect Britain’s international standing. More than 1,000 Japanese firms operate in the UK and they employ something like 140,000 people. Their total investment in the country amounts to £40bn.

Japan’s major carmakers thus far have indicated that they will remain true to the UK. Toyota (GB) PLC has recently announced a £240mn investment in a car assembly plant in Derby and Nissan Motor (GB) Limited has committed to building its new Qashqai model in Sunderland.

And there are signs of confidence in other UK sectors. For example, late last year SoftBank Group mounted a £24 billion takeover of Britain’s most valuable technology firm, ARM. Some are keen to stress the advantages of the UK, such as its legal system and financial expertise. Yet Japan’s biggest business lobby, the Keidanren, has voiced concerns over post-Brexit risks to both the British and Japanese economies.

The proposed EU–Japan free-trade agreement is no doubt good news, but hopes will now be focused on a similar agreement between Japan and a post-Brexit United Kingdom.