The short life and tragic death of 10-year old Mia Kurihara horrified the nation in 2019. While others wrung their hands at the killing of a child aged 10 by her own father and the failure of a system that is meant to protect the most vulnerable in society, Caitlin Puzzar set about trying to tackle the problem of abuse in Japan.

App inspiration

Originally from the Mossley Hill district of Liverpool, 26-year-old Puzzar is an assistant language teacher with the JET Programme. She has been based in Kumamoto City since arriving in Japan in July 2016. Very soon after entering the Japanese education system, she began to notice serious deficiencies in how data on problems that children are experiencing—from bullying to neglect—was being collected and stored, as well as the people who had access to the sensitive information.

Originally from the Mossley Hill district of Liverpool, 26-year-old Puzzar is an assistant language teacher with the JET Programme. She has been based in Kumamoto City since arriving in Japan in July 2016. Very soon after entering the Japanese education system, she began to notice serious deficiencies in how data on problems that children are experiencing—from bullying to neglect—was being collected and stored, as well as the people who had access to the sensitive information.

“I was in the staff room in one of the schools where I teach and I noticed that a stack of the written questionnaires that the children have to do now had just been left in a pile on a desk and were there for anyone to see”, she said. “Information like that is extremely sensitive and private and should not be so easily accessible”.

Puzzar, who has a degree in criminology from Keele University, England, subsequently took part in a two-day course organised by the Japan Institute for Social Innovation and Entrepreneurship and Kumamoto Prefecture for people who had an idea for a project that could help society, but lacked the knowledge and contacts to turn that idea into a product or service.

Building on a concept put forward by Puzzar, her team developed an app that children could use to safely inform authorities that they were being abused. The app would also protect their identities from school officials who did not need to have access to the data and, critically, conceal answers from parents and other possible abusers.

Grounds for action

The death of Mia Kurihara served to crystalise the need for such a system.

On repeated occasions, Mia had filled in questionnaires at school—that she believed were confidential—in which she stated she was being abused by her father over an extended period of time. Child services in Chiba Prefecture took her into protective care, but handed her back to her parents one month later. Officials at her school also gave in to her father and provided him with a copy of Mia’s questionnaire.

She died in January 2019 after being denied food and sleep and forced to take repeated cold showers at the family home. Her father, Yuichiro Kurihara, 43, was found guilty of causing her death and sentenced to a 16-year prison term in March 2020. An appeal against the sentence, on the grounds that it was too severe, was rejected in March.

Nine months after Mia’s death, Puzzar travelled to Tokyo to explain her idea to an angel investor, who immediately saw the potential and snapped it up.

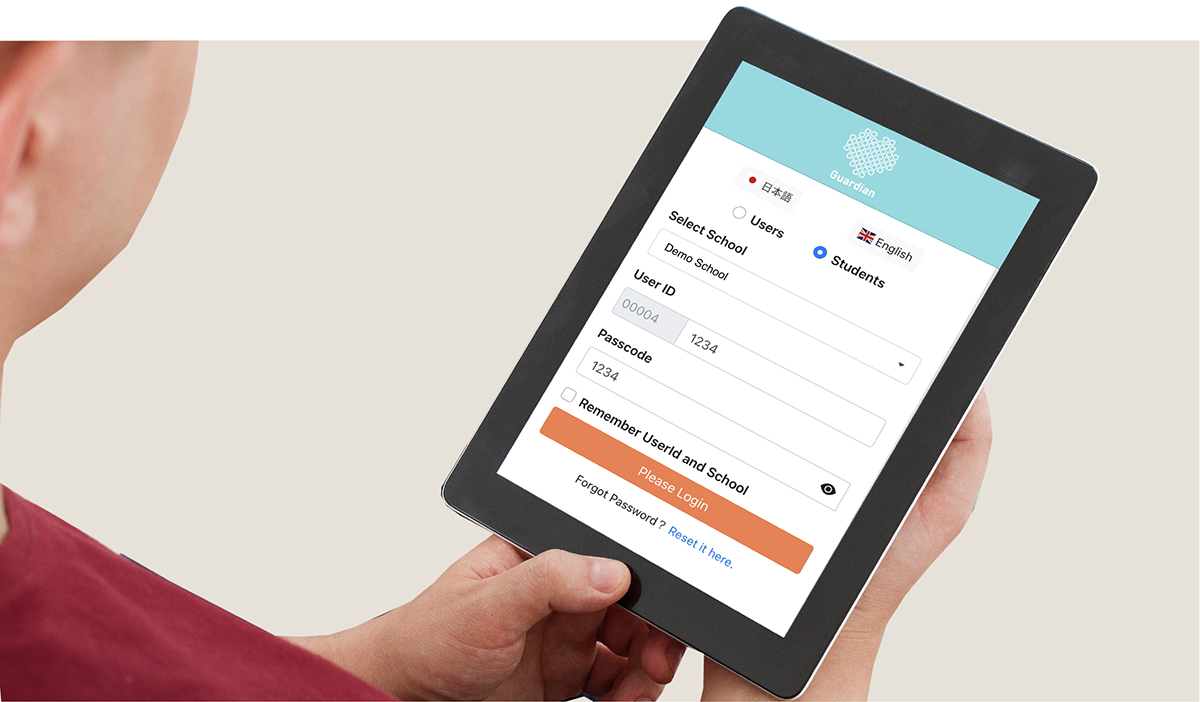

She worked with software developers in the early part of last year before requesting permission from the Kumamoto City Board of Education to test the app, named Guardian, in the three schools where she works. At present, about 1,000 students in a junior high school and two elementary schools are putting the system through its paces.

How it works

Pupils are assigned randomly generated individual IDs and passwords to log in and complete questionnaires on a daily, weekly and monthly basis. At the most basic level, the app inquires how a child is feeling and whether he or she has eaten breakfast that morning, had a bath and seeks replies to some other questions about basic care.

The more in-depth monthly questionnaire is designed to elicit responses that indicate whether a child is the victim of abuse. The app also uses a colour-coded scale, with a yellow, orange or red alert displayed for any child that needs protection.

The information is carefully protected, with only senior school officials and school healthcare workers able to access all the details. The system also incorporates an SOS button for a child to press for immediate assistance.

Push back

Puzzar admits that she has come up against a degree of resistance from fellow teachers on the grounds that the app suggests that they are not doing their job properly, but the city board of education has been supportive.

Most importantly, she said, children appear to be using the app and it has already identified potential cases of previously unknown issues and abuse, enabling authorities to step in.

The original idea has already undergone a number of modifications and updates, with Puzzar expressing hope that the local education authority will approve its deployment in about 40 junior high schools and 90 elementary schools across Kumamoto City from the start of the new year in April.

Puzzar hopes to continue to refine the app and, potentially, take it to the rest of Japan and even other countries. When her JET placement comes to an end, she hopes to work for a child-focused organisation such as Save the Children. But ultimately Puzzar would like to be involved in child protection work in the UK for the National Crime Agency.

“I’m really pleased with how it is working out, and if the app only helps a few children in difficult situations, then it will have been worth it”, she said.