Firms in the global finance sector are keeping a close eye on developments in Hong Kong, after the Chinese government passed a controversial national security law on 30 June. The vast majority, however, are reluctant to speculate on whether they will relocate at least part of their regional headquarters’ operations elsewhere as a result of local instabilities.

But that is exactly what the Japanese government hopes many will do if Beijing’s new regulations make it increasingly difficult for firms or individuals to remain in the former British colony, which is today recognised as one of the world’s leading financial hubs.

Time to move?

Hong Kong has been racked by civil unrest in recent years as local residents protest the erosion of their rights, culminating in the passage of the national security law. In response, Britain has offered as many as 3mn Hong Kong residents the opportunity to settle in the UK and, ultimately, apply for citizenship. Australia is giving a further 10,000 Hong Kong passport holders the right to apply for permanent residency.

Beijing has angrily criticised both London and Canberra, but a poll by the Ming Pao newspaper in late June found that more than 37% of Hong Kong residents are actively looking into moving abroad.

Hong Kong is also caught squarely in the middle of the ongoing trade war between the United States and China, while US President Donald Trump signed an executive order in mid-July ending Hong Kong’s preferential trade status, ruling out special privileges and providing “no special economic treatment and no export of sensitive technologies”.

Speaking on the condition of anonymity, one senior executive of a global financial firm with its regional headquarters in Hong Kong admitted to ACUMEN: “There is serious concern over the possible unknown right now, for sure. If [the Chinese Communist Party] does not soften its approach, then there could ultimately be serious effects and businesses migrating away from Hong Kong” over the next decade or so, they said.

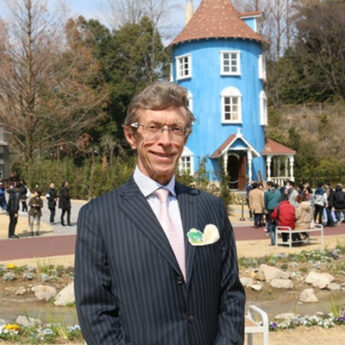

James Dodds, a partner with KPMG Tax Corporation in Tokyo and a member of the Executive Committee of the British Chamber of Commerce in Japan, points out that there are considerations beyond the political and economic implications of uncertainties in Hong Kong.

“I am not aware of any firms actively looking at moving from Hong Kong,” he said. “On the other hand, I think the Covid-19 pandemic is causing firms to look at their business models and where they locate their staff, among other issues.

“The changes in Hong Kong, and other geopolitical events, are additional factors to take into consideration,” he added. “Clearly, if there are major changes in the legal or economic environment, then firms need to consider the impact—but that does not necessarily mean they will change anything.

“Also, if there is change, it does not always need to be all or nothing. It could be a gradual movement of operations from one country to another”.

Eyeing Tokyo

Doug Tucker, the Hong Kong-based regional manager for financial advisers DeVere Group, believes it is “too early to say” what the impact of recent developments in the city will mean for international firms. But if his head office does decide to relocate its Asia–Pacific headquarters, he hopes Tokyo will be his next destination.

“Tokyo has high-quality and educated employees, it is a clean and safe city, and it has a decent legal system,” he cited as reasons it edges out Seoul and Singapore—even though that city-state has the advantage of English being widely spoken. And that will be music to Japanese authorities’ ears.

Initiatives

In June, the government unveiled a series of initiatives designed to appeal to foreign financial firms, with Prime Minister Shinzo Abe pointedly declaring that Japan would continue to welcome “foreign talent with specialised and technical abilities, including from Hong Kong”.

In the 2019 upper house election, the ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) made a point of calling for Tokyo to evolve into a global financial hub on a par with London and New York. The party set up an economic growth strategy group and drew up a list of recommendations, which include relaxing existing banking regulations, improving governance and a placing greater focus on environmental and social issues.

The proposals also include the introduction of new workstyles, such as telecommuting, as a result of the coronavirus pandemic, a fast-track and simplified system for permanent residency, tax breaks, reduced corporate rents and the adoption of 5G wireless technology.

In an interview with Bloomberg, Satsuki Katayama, the minister who heads the LDP panel on foreign labour, said: “What Japan offers that Hong Kong doesn’t is freedom. If Hong Kong becomes the kind of place where people’s Facebook likes are being checked, will they put up with that? I think people want to live somewhere normal”.

She admitted that Tokyo does have a number of disadvantages compared with other cities at present, but expressed hope that those might be ironed out fairly swiftly. One possibility is a new visa status that does not require full residency, Katayama said, along with an “offshore” zone that would be separate from Japan’s existing taxation system.

To appeal to families, more international schools will be given opportunities to set up campuses in Tokyo, while additional support will be drawn up for visas for assistant staff.

“Since the issue of attracting foreign firms to Japan has been looked at several times in the past, the government should have plenty of information on the issues, so they need to examine why it has not worked in the past, such as by speaking to regional headquarters in other locations,” said KPMG’s Dodds. “And then they need to decide whether they are willing to make the change that would make a difference this time”.