Business was brisk at the 15th annual Pyongyang Autumn International Trade Fair, while Asians and Europeans also kept the tourism industry busy on my recent trip to the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK)—that’s North Korea—where the rules, people and borders were remarkably open and flexible.

With 187 Chinese booths, there were 360 global exhibitors openly offering for retail or wholesale everything from luxury yachts, Lexus cars and mid-sized trucks to ginseng, massage tools, drones, “instant and perfect cures”, canned soda and coffee stamped with a London address. Electric bicycles went for $300–500—although most prices were in euros due to the dearth of American visitors. Anything with Disney characters drew a queue. I also heard haggling in Italian, East European and Southeast Asian accents near booths for electronics, machinery, metals, construction materials, transport, medicine, agriculture, artificial intelligence products, light industry, luxuries and food.

On the streets and at the main tourist spots, the 2018 book by Travis Jeppesen, See You Again in Pyongyang, came to mind when I encountered a British woman on her third visit in two years, another European on his second trip in 12 months, and a mixed Western group of about 10 enjoying their 23rd consecutive day and already planning to return.

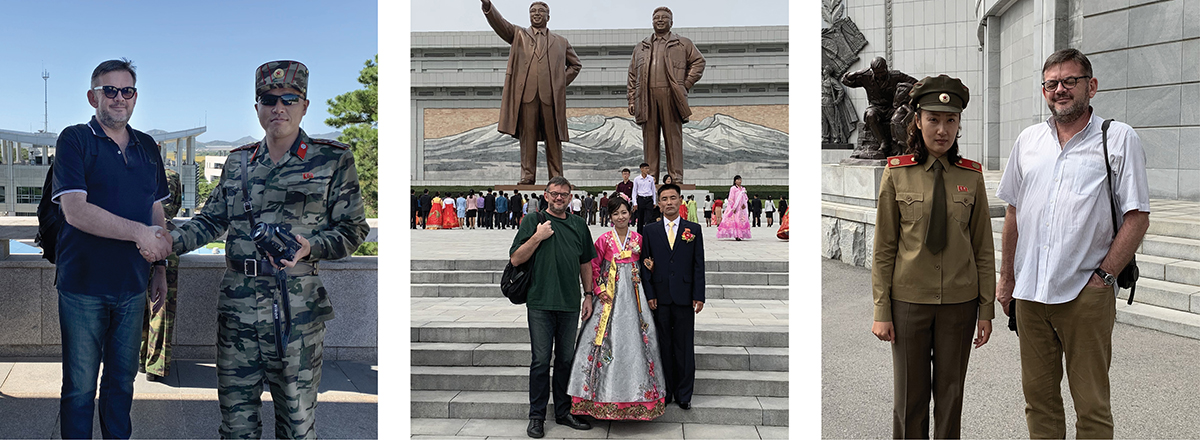

Surprisingly, I was allowed to photograph almost anyone and anywhere in public—except the most revered or sensitive spots. Contrary to reports of foreign tourists being compelled to respect certain sites, an Australian with me politely declined to view the ghoulish mausoleums of Kim Il-sung (1912–94) and his son Kim Jong-il (1942–2011) due to his Christian sensitivities. Our minders happily allowed him to stay on the bus.

We were forbidden to leave our hotel grounds unescorted, but there was no obvious security to enforce this. Accommodation was in an ageing skyscraper on an island near the Pyongyang city centre and a traditional and basic single-story ryokan-style inn, enclosed by high walls and a deep moat, near the Korean Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) at Kaesong, a three-hour drive from Pyongyang. Much of the last 48 hours, however, was spent without minders at the bustling trade fair and in a six-bunk sleeper cabin with locals on the overnight train back to Beijing.

But I was proudly dismissed with contempt when I asked about email and Wi-Fi: My minder harrumphed: “North Korea doesn’t have internet; we have intranet”.

Visitors can bring cameras, cell phones, laptops, notebooks, pens, recorders and any device (except those equipped with GPS), as long as you declare them on arrival. And hotel guests could call abroad from their room.

British, Japanese and many others are welcome, but not South Koreans. North Korea welcomes Americans, but the United States bans its citizens from going there. British and other visitors to the United States who have been in North Korea since March 2011 are ineligible for the visa-free ESTA programme available to 37 nations.

What’s on the itinerary?

What’s on the itinerary?

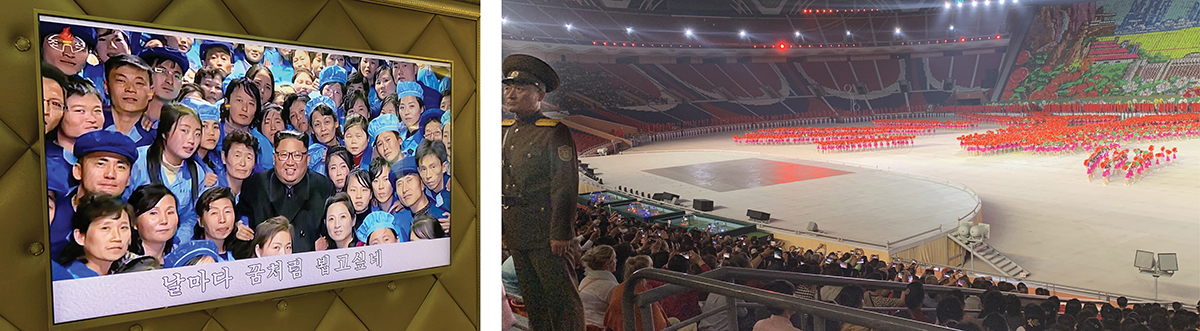

As I had been declined a visa by North Korea several years earlier, I was relieved to be quickly approved after booking online with a UK-run travel agent in Beijing. As well as the trade fair, the package featured Pyongyang’s epic Arirang Mass Games gymnastics spectacle and its 17th International Film Festival, plus visits to the contentious DMZ, UNESCO World Heritage Sites, mausoleums and “war crime” museums, as well as the atheist nation’s 14th-century Buddhist and Confucian tombs and temples.

The smooth 90-minute flight from Beijing to Pyongyang was apparently well stocked up for the trade fair, with tons more goods than passengers at check-in.

Spotless and efficient, Pyongyang International Airport officially serves only China and Russia. Friendly officers didn’t open my bags or notice the wrong passport number in my tourist card visa. After the pleasant 20-minute minibus drive along orderly streets lined with colourful flowers, we pulled up at the imposing 47-storey Yanggakdo International Hotel.

A minder kept my passport and paranoia set in as I scanned the hammer-and-sickle propaganda art on corridor walls and remembered Otto Warmbier. The American student died in 2017 of “botulism” or “torture” soon after serving hard labour for allegedly stealing art from his hotel. This hotel.

North Korea does not spy on guests, however, I was assured by industry insiders I had met in Beijing who requested anonymity. “As if the North Koreans have the time, resources and incentive to watch every guest 24/7; and what would they learn, anyway?” One British businessman who frequently visits Pyongyang told me his colleague’s bathroom ceiling once fell down and he “looked up but couldn’t see a camera”—so that’s alright then! “And everything’s been reported anyway, so who cares what foreign journalists write?”

First night fail

I was looking forward to the featured movies Run and Run, My Mother Was a Hunter and O, Youth! But the promised film festival opening ceremony tickets failed to materialise. I was treated instead to a private showing of Comrade Kim Goes Flying, a 2012 British–Belgian–North Korean romantic comedy.

At the Grand People’s Study House (central library), which “holds 30mn”, British (and other foreign) dog-eared publications and music CDs were available in minutes on written request. They included Harry Potter, Jane Eyre and Oasis.

Minders often tried to divert me to tombs and temples (there’s even a granite monolith devoted to the Dear Leader’s signature!), but they are hard sells to cynical travellers against classic draws such as these:

- A ride with friendly and curious commuters on Pyongyang’s cavernous subway of colourful murals, plunging escalators (so long and slow that some passengers squat down to nap), extravagant chandeliers, marble floors, as well as cheeky school kids who practiced English with me and a pensioner who offered me his seat.

- Posing for selfies as you stretch your legs under the actual table and sit on the actual seat in the actual room, unchanged (except for added air-conditioners) since 1953, where the Korean Armistice Agreement was signed and is displayed, at the DMZ.

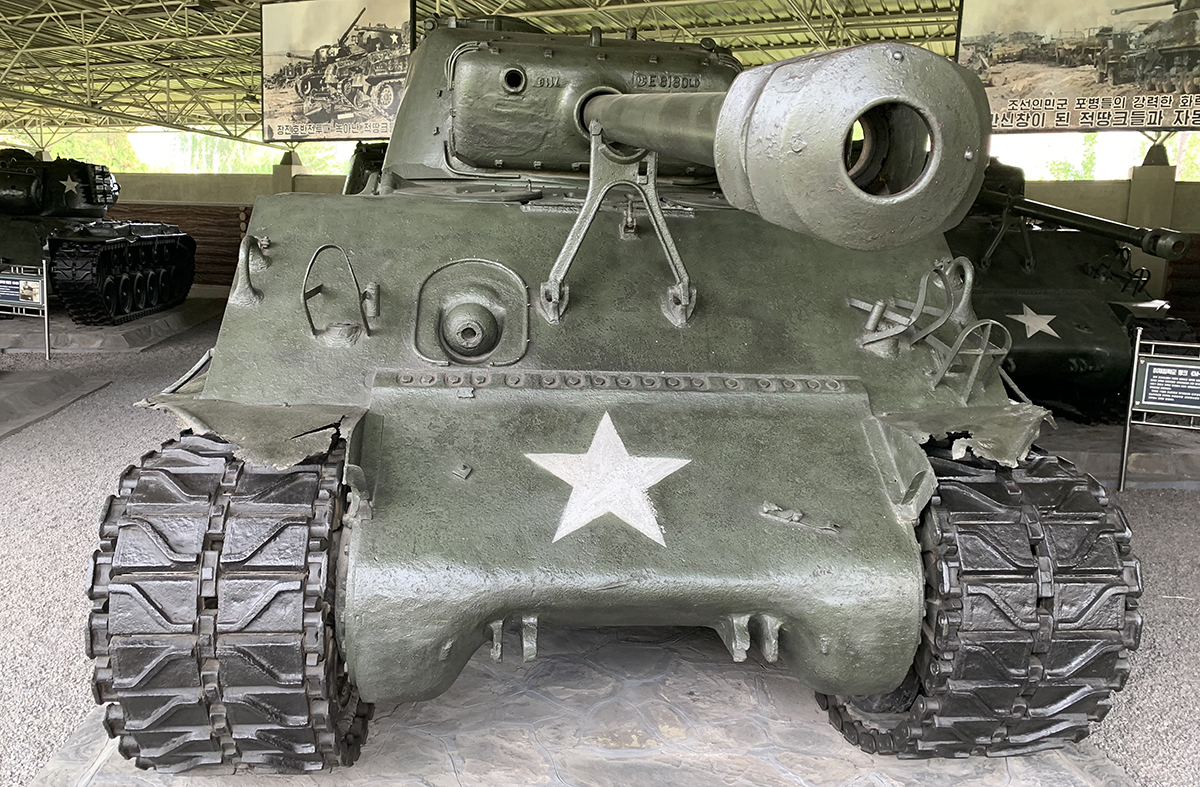

- Marvelling at the Victorious Fatherland Liberation War Museum as a revolving circular centre stage slowly glides you on a macabre 360-degree pilgrimage through a theatrical 3D battleground. The performance features gruesome sound effects, bloodied and battered mannequins with missing limbs, as well as scattered personal and military items from captured enemy in the Korean War (1950–53).

- Visiting the innocuous-sounding Kumsusan Palace of the Sun—my favourite site—which displays in transparent coffins the embalmed remains of North Korea’s designated “eternal leaders”, founder Kim Il-sung and his son Kim Jong-il.

Even if you’ve seen the mausoleums of Vladimir Lenin, Ho Chi Minh and Mao Zedong, this 10,700m2 pile is the world’s largest and most extravagant of modern times. One room alone measures a full square kilometre.

Visitors must deposit at reception any wallets, bags, electronic devices, cameras, cell phones, pens, sunglasses and thick-frame eyeglasses; written rules ban shorts, hats, T-shirts, open shoes, eating, drinking, smoking, smiling and pointing; smart wear with collar, tie, socks and laces are de rigueur.

We were transported at a steady pace under strict orders to stand ramrod straight, arms by our sides and dead still for about 1.5km along a subterranean walkway lined with portraits and landscapes. Armed men in dark suits and combat fatigues glared from behind dark glasses. We stumbled over damp shoe sole-cleaners and squeezed through 2m-high powerful arched fan-blowers—both to detect hidden devices and remove dust harmful to the sterile environment.

In groups of four, we were finally led in to bow deeply at the feet and sides of both bodies in separate chambers. There was total darkness except for the blood-red spotlights illuminating the ghostly pale eternal leaders. We were then whisked though two rooms of ceiling-high glass cases displaying many of their clothes and weapons as well as presents, medals, awards and certificates from governments, universities and other organisations in mostly communist countries or other dictatorships.

On the last evening, after the trade fair, I got permission to swap our group’s farewell dinner for refreshing sundowners in our hotel rooftop’s revolving restaurant—accompanied by a minder. Over Budweiser and a ¥1,200 bottle of Italian wine, we rested our tired feet to soak up the classic sunset view below of the brief rush hour and muddy Taedong River winding through the faintly lit streets and dark, distant suburbs.

My minder revealed there was a casino in the hotel basement, but only for foreigners, so we agreed I would go there alone and meet again later. In the lift down, a British woman from the travel industry based in China whispered to me as she texted that, yes, you could get free Wi-Fi in the casino. I followed her vague directions via a dusty labyrinth of dark, empty, silent corridors with low ceilings along a pungent trail of cigarette smoke and unmistakable sounds of slot machines and shouting in Chinese. After sheepishly entering one of the country’s three legal casinos, I asked for €10 (¥1,200) of chips, and the cashier also gave me the Wi-Fi password. She pointed me to the best hotspot where I sat to exchange instant LINE and email texts with startled friends and colleagues in Tokyo and London; one was convinced I had been kidnapped or my phone had been stolen or hacked.

My minder revealed there was a casino in the hotel basement, but only for foreigners, so we agreed I would go there alone and meet again later. In the lift down, a British woman from the travel industry based in China whispered to me as she texted that, yes, you could get free Wi-Fi in the casino. I followed her vague directions via a dusty labyrinth of dark, empty, silent corridors with low ceilings along a pungent trail of cigarette smoke and unmistakable sounds of slot machines and shouting in Chinese. After sheepishly entering one of the country’s three legal casinos, I asked for €10 (¥1,200) of chips, and the cashier also gave me the Wi-Fi password. She pointed me to the best hotspot where I sat to exchange instant LINE and email texts with startled friends and colleagues in Tokyo and London; one was convinced I had been kidnapped or my phone had been stolen or hacked.

After a week of online silence, I also enjoyed the BBC, Japan News and extensive googling to catch up on five days of missed news. I recalled with a smirk: “North Korea doesn’t have internet; we have intranet”.

Perhaps it was good that I hadn’t discovered this hack on my first night.

Finally, I unwound at the end of the trip on the optional 23-hour Pyongyang-Beijing express to freely mingle with locals without minders and buy late souvenirs on frequent stops at station platforms.

North Koreans don’t like it if you:

- Offer to buy the Kim badges compulsory for adults to wear in public; they are very hard to replace and illegal for foreigners to possess

- Fold, point at or place upside down images of living, deceased, supreme or eternal leaders

- Sit on anything in public except a seat

- Display too much bare skin

- Ask political or personal questions

- Ask for North Korean currency

But why visit North Korea?

The Kumsusan Palace of the Sun

To view the preserved remains of Kim Il-sung and Kim Jong-il lying in state, bathed in blood-red light inside their transparent crystal sarcophagi.

Pyongyang International Trade Fair

From practical to luxury, the annual autumn and spring trade fairs defy various United Nations, EU and countries’ sanctions.

Stalls offer products for import and export that are made locally, regionally and globally, such as electric bicycles, small yachts and tractors.

Korean Demilitarized Zone and the original Korean Armistice Agreement established to end hostilities

To sit where it was signed in 1953, and to endure loud lectures on “American imperialism.” Located an uneventful three-hour drive from Pyongyang, with farmers and builders toiling alongside the pothole-scarred road to Kaesong—our only rural view of the week.

Pyongyang’s marbled subway

Claims the world’s longest murals, deepest escalators, and cheapest tickets.

Victorious Fatherland Liberation War Museum

An eerie monument to perceived injustices and victories. You are taken, seated, on a moving 360-degree journey around a movie-set-like bloody battleground, and graphic exhibits of captured enemies’ personal and military items.

The 23-hour Pyongyang-Beijing train

To freely mingle with locals without minders; enjoy brief souvenir stops and a cozy restaurant car.

The UK Foreign & Commonwealth Office advises against all but essential travel to North Korea: www.gov.uk/foreign-travel-advice/north-korea