Latest on inbound and outbound M&As in Japan

Times of uncertainty tend to witness a dampening down of economic activity in general, and riskier deals such as mergers andacquisitions (M&As) in particular. However, the post-disaster environment appears to be focusing the attentions of Japanese firms on buying abroad, even as the strong yen and challenging domestic economic landscape have not put paid to all inbound M&As.

A quick glance at the Nikkei one day at the end of July reveals the amount and diversity of activity taking place in the M&A arena.

- Osaka-based medical-equipment specialist Nipro is buying US and European medical-glass businesses, forming a Russian joint venture, and taking a majority stake in an Indian maker of medical containers.

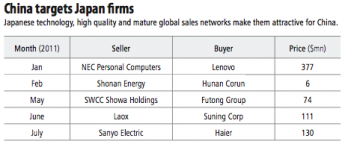

- Haier Japan Sales Co., Ltd. is taking over Sanyo Electric Co., Ltd.’s washing machine and refrigerator businesses in Japan and South-East Asia, marking the first acquisition by a Chinese firm of a major division of a Japanese manufacturer.

- A KDDI Corporation subsidiary— that last year built a strategic alliance with a Californian firm—is taking over a domestic mobile-phone advertising company and is planning to expand into the wider Asian smart-phone advertising market.

The strong yen is providing a double stimulus to outbound M&As, increasing the already considerable purchasing power of Japanese firms and making domestic production less competitive.

“Looking at deals made by Japanese firms over the past 12 months, they are getting bigger and happening more frequently; that is a reflection of the cash that they have built up over the years, and the amazing state of the currency markets”, said Yuuichiro Nakajima, managing partner at Crimson Phoenix, which acts in an advisory capacity on inbound and outbound M&As.

“Japan is at a huge disadvantage on price, particularly because of the strength of the yen”, said Nakajima, “so foreign takeovers, in which some of the production may be moved overseas, are an opportunity to change the cost structure of the firm”.

According to Kenneth Siegel, head of Tokyo operations for Morrison & Foerster, the biggest international law firm in Japan, this is the first time that Japanese firms are taking full advantage of the yen’s strength.

“For the past 10 years, when the yen has appreciated, Kenneth siegel Japanese companies have done less M&As”, said Siegel. “It was always surprising—but frankly, the Japanese firms were always more focused on the effects of the strong yen on their core business in Japan, and less focused on its positive effect on their acquisition currency”.

Just how long this window of opportunity created by the currency markets may be open is uncertain.

“Some business leaders think the yen can’t stay this strong for a long period and so those companies looking to invest outside Japan see this as a prime time to do so”, said Patrick Shearer of the M&A Transaction Services team at Deloitte Tohmatsu.

In the past, an event such as the 11 March earthquake and tsunami may have shocked Japanese firms into semi-paralysis in terms of M&As, as the strong yen once did. However, this time their response appears very different.

“We think the earthquake will encourage outbound M&As, not so much because firms will move production out of Japan—which they will do through the organic redeployment of resources—but because more companies will see more pronounced downward trends domestically, and will see a better rationale for moving abroad”, said Siegel.

Ernfred Olsen, head of Japanese operations for the Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS), also sees the weak home market as the major impetus for domestic firms ramping up overseas expansion.

“There’s been an enormous change in the past few years; Japanese companies have given up on growth domestically, so they’re exporting huge amounts of capital”, said Olsen.

“In the Nikkei you can see every day that companies are investing offshore. There’s some rebuilding in the Tohoku region due to the disaster, and some of the most sensitive technology is being kept in Japan, but everything else is going overseas”.

With the increased amount of overseas takeovers, Japanese firms are becoming more adept at types of transactions about which they have little experience at home, where aggressive acquisitions remain a rarity. The next step is for them to successfully manage and integrate their new subsidiaries.

“Japanese firms going offshore have been much more successful in recent auction bids and hostile M&As than they have been historically. In the past, Japanese firms would tend to develop a strategic relationship with a company in their own business area, then develop a preferred relationship and, ultimately, acquire the company in a one-on-one negotiation”, said Morrison & Foerster’s Siegel. “In recent years, they’ve been much more active in bid situations, and much more successful in those situations”.

“For example, we represented Astellas Pharma in its unsolicited acquisition of OSI Pharmaceutical for $4 billion last year, which was the first successful hostile takeover of a US firm by a Japanese company”. Although corporate Japan has a reputation for slow decision- making, the need to move quickly in the overseas acquisitions market has led to a streamlining of that process in recent years, according to Deloitte Tohmatsu’s Shearer.

However, Japanese firms still have a way to go in terms of internationalisation and personnel who can run foreign entities, believes Crimson Phoenix’s Nakajima.

“One of the common concerns that appear when Japanese companies think about making an overseas acquisition is whether they can actually manage the company. It’s not just a language issue, but whether they have managers who can operate in two or more languages is a big concern”, he said. “I do hear from Japanese companies that they are interested in a takeover, but don’t have the personnel to integrate the acquisition”.

He believes that there is some progress being made on this front, with more Japanese firms appointing foreign directors to their boards, and even chief executives, such as at Sony Corporation, Olympus Corporation and Nippon Sheet glass Co., Ltd.

“The proof of the pudding—the success of the recent overseas buying spree by Japanese companies—lies in whether they can make those acquisitions work”, said Nakajima.

“Foreign companies buying in Japan face the same challenge—whether they can be represented effectively and efficiently on the board of their acquisitions”.

“I believe that, so far, Western firms buying Japanese companies have been better at bridging that gap than the other way around.

Collectively, the average UK or US company has greater experience in overseas acquisitions than the average Japanese company”.

However, with a strong currency making Japanese acquisitions expensive, a stagnant domestic economy and residual cultural resistance to being taken over by outsiders, many would question why foreign firms would target enterprises here. And yet such deals are conducted.

“What foreign acquirers may be looking at in thinking about Japanese targets now, in a market with a shrinking population and a catastrophic political environment, is access to new markets through key customer relationships, as well as technology and skills”, said Nakajima. “For companies looking for those things, there are plenty of potential targets”.

“There’s more inbound than I would have thought. There is a big reshuffling/ restructuring by firms such as the Japanese trading companies, which are selling off bits of their empires as they refocus their strategic efforts”, added Olsen from RBS.

“I ask our international clients why they are looking at acquiring in Japan, with almost no prospect of growth in domestic markets and an incredibly strong yen—and likely to get stronger— which makes acquisitions very expensive”, he added.

Their rationale, according to Olsen, is that: “So many service companies are so undermanaged that, if they can get to 75% of global KPI [key performance indicators] they can make returns. These aren’t the huge headline-grabbing deals, but they can bring value to companies here”.

Retail, in particular, remains an area in which high margins, at the luxury end of the market at least, can be protected more successfully than they can in other territories. “Japan is still, however you measure it, a very wealthy society, so the consumer sector remains attractive”, pointed out Shearer.

Olsen believes that, like the service sector, “the financial sector is also full of inefficiency, but there haven’t been many happy stories from takeovers in that area”.

Other sectors with appeal for overseas investors include life sciences/pharma and electronics manufacturing, “two sectors, with too many small companies, which should see further consolidation,” according to Peter Wesp of Ernst & Young’s Transaction Advisory Services division.

While there are now few regulatory hurdles for inbound M&As, cultural resistance does remain an issue.

“There are hardly any legal barriers for foreign investors buying businesses in Japan”, said Wesp. “Language and cultural barriers exist, but they exist in many other countries, too, and they can be overcome”.

Traditionally in Japan, maximizing shareholder value has been way down the list of priorities for corporations, although that, too, may be starting to change.

“The emergence of private equity funds over the past ten years or so has definitely changed the mindset of people, from thinking of companies merely as a community of inside interests or internal stakeholders, to a thinking that gives more respect to outside capital providers”, suggested Nakajima.

“People have realised that these outside capital providers may be able to add value in terms of solving problems of succession, currency strength and cost restructuring”.

Foreign private equity has had a famously tough time in Japan, though there are signs it hasn’t given up the ghost quite yet.

“There is still some of the anti-foreign- takeover sentiment that scared off most of the global private equity firms, or they just got tired of it and headed for greener pastures”, said Nakajima. “However, after each deal, people get more used to it”.

Siegel believes that global private equity may stage something of a comeback. “They had always struggled against domestic private equity because of their expectations for return. With domestic firms now less active, there could be more opportunity for them”.

Many of the major private equity players still have offices in Tokyo, points out Deloitte Tohmatsu’s Shearer. “Bain, Blackstone, KKR, TPG, Carlyle, Permira and CVC, they are here and looking to do deals”, he noted. While the strength of the yen is a major factor for private equity, for companies expanding operations in Japan through M&As, it may be less of a burden.

“Very few companies come and buy a business as a market entry strategy. Most will already have set up some kind of operations in Japan, and so have local currency revenue”, suggested Nakajima. “So, while they may have to borrow to finance the acquisition, if they’re expanding an existing business, the strong yen shouldn’t worry them too much”.

The biggest barrier to acquisitions in Japan, though, is a lack of firms interested in being taken over. Entrenched conservatism on the boards of many Japanese firms remains strong, but that may be beginning to change.

“Many salaried employees sit as board members—with low salaries and big retirement benefits—serving in the interests of the company rather than its shareholders”, said Ernst & Young’s Wesp, “with little incentive or upside to taking any risks”. Some, however, do see a shift occurring. “The evolution of management thinking in Japan is on a trend that will be hard to stop. Unless you are a company that is completely contained in Japan and focused solely on the domestic market, M&A is now a part of life”, said Nakajima. “Corporate Japan is slow to change but, once it starts, it moves at a fairly smart pace”.