British researcher Warren A. Stanislaus first visited Japan in 2006. An alumnus of the International Christian University in Tokyo,

where he graduated with a Bachelor of Arts in liberal arts, Stanislaus is currently a PhD candidate at the University of Oxford.

Previously he gained a Master of Philosophy (MPhil) in Japanese from the University of Oxford’s Nissan Institute of Japanese Studies, before returning to Japan and working at the British Council’s Tokyo office for a year. Stanislaus was also a researcher at the Asia Pacific Institute of Research, a Tokyo-based think tank.

In a wide-ranging interview with BCCJ ACUMEN, the academic-turned-social commentator speaks about his first impressions of living in the Japanese countryside as a young man, Black History Month and UK–Japan relations.

How did you end up in Japan?

My first route to Japan was on a gap year programme in 2006. Just after I had graduated from secondary school, my goal was to go to a university in the UK to do Japanese studies, but I had deferred that. I thought, ‘Look, before I go to university, I should spend some time in Japan and try to pick up the language.’

I spent six months living and volunteering in a care home for the elderly in Aichi Prefecture for half of the week, and the other half I was volunteering in a kindergarten. Due to the nature of the work, I got exposed to Japan as it is for children and for people in the twilight years. It was a really cool first experience of Japan.

It was from those experiences—being in the kindergarten, for example, and seeing how the kids were learning the Japanese language and culture— that I started to realise that, if I’m going to pursue Japanese studies, then it’s much better to be here, because there’s so much more to it than just the language: there is also the tacit communication and the different cultural aspects that you pick up by just being here.

Please tell us about your first experiences in Japan.

It was in Aichi Prefecture, in a city called Nishio. The city itself has a population of around 100,000 in 2006, so it’s not that small. But, coming from London, it felt like the countryside—there were fields everywhere. That shaped my first impressions of Japan.

Surprisingly, I actually found Japan to be quite diverse. In the school where I volunteered—and thinking about Aichi Prefecture and the firms there, such as Toyota and its related businesses—there were lots of Brazilians of Japanese heritage with children in the kindergarten. There were also a lot of Southeast Asian kids in there as well.

This was not something I had expected. I was quite surprised that I was first exposed to Japan as being a diverse place with lots of cultures … So that was a fascinating first experience for me.

More broadly, those first six months made me want to stay on longer. People were so friendly in terms of how they treated me and the other gap year volunteers. They treated us as their guests and they took us around to experience their culture and food.

The last thing I’ll say about my first impression of Japan is that, I think it was also shaped by the content to which I had been exposed while in the UK. For example, there was this TV show called Japanorama, with Jonathan Ross. It was about Jonathan Ross going around Japan to maid cafés, seeing cosplay in the streets, and all the stereotypical images of a wacky or futuristic Japan.

So, you come to Japan with those expectations, and you’re looking for that. Obviously, some of those things may have happened in the late-1980s or mid-90s, but coming here in the latter years of the 2000s, there wasn’t much of that going on.

Especially being in the countryside, life was rather mundane. It was very quotidian and there was not a lot going on. That was quite a shock, for me … but it allowed me to develop new interests in Japan.

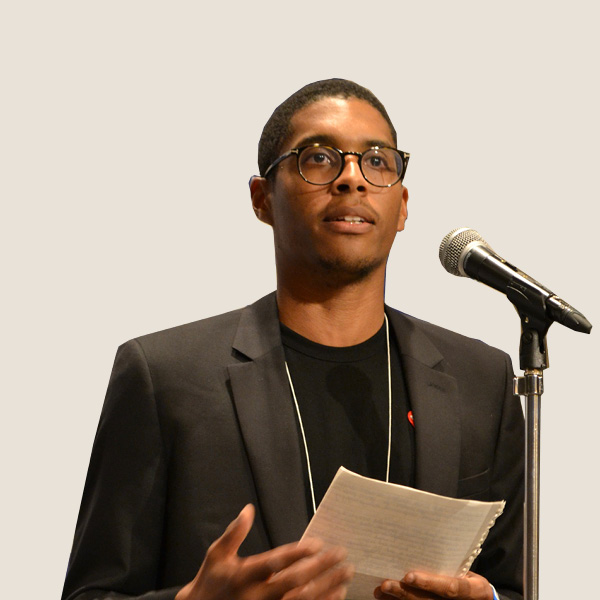

Stanislaus while studying at ICU

What can you tell us about being a foreigner here?

I think that some of the experiences will be quite similar to those that other foreigners mention about their time in Japan. For example, the challenges of renting an apartment, and being questioned about what nationality you are.

And then there are the times when people are hesitant about sitting next to you on the train. Or generally being treated like an oddity in some way— and that can be a positive thing.

It also goes back to the point about Japanese hospitality, and people treating you in a special way.

For example, my simply saying I’m from the UK means I can get certain privileges, and be treated in a good way. On the other hand, being an outsider can be negative, for various reasons.

I think those are some of the similarities experienced by many foreigners, regardless of nationality. I find that quite levelling, that you share these commonalities with non-Japanese people in Japan, regardless of race or background. That means you can connect with other people with whom you perhaps wouldn’t have shared commonalities had you just stayed in the UK.

Stanislaus was named third in the 2019 Rare Rising Stars awards for the top ten Black students in the UK.

Can you talk about your experiences here as a Black person?

I’ll compare them to my experiences in the UK. For example, when I was in Oxford fairly recently, at the start of my PhD, there was a student who, as we sat at a table during one of the welcome weeks and doing introductions, I was explaining how I had lived in Japan for a long time and that I was there doing Japanese history.

Five minutes later, he comes to me and says, “Oh, are you doing African studies like those guys as well?”—and by “those guys” he meant some Black students nearby. But they weren’t doing African studies either: one of them was doing Latin American studies and the other one was doing diplomatic studies. So, whatever I said, it’s as though the Blackness is what’s being understood; the Blackness speaks loudest and holds more meaning.

But in Japan, despite initial stereotypes—such as, “Oh, you can dance well, You’re good at sport”, or, “You have long legs”, all those types of things— when you start to talk to people, whatever you say to them takes precedence, and informs their opinion of you, rather than your skin colour. That’s one big difference in terms of Japan in comparison with some of the negative experiences I have had in the UK.

What has been your connection to Black History Month?

What has been your connection to Black History Month?

It became more urgent, especially in the wake of the mainstreaming of the Black Lives Matter movement last year and the death of George Floyd. That was a moment when people’s ears were more open to listening to discussions about, for example, Black History Month.

So, it was a good opportunity for me to reach out to the British Embassy Tokyo, and they were very happy to organise something around that. We produced [an article and video] in Japanese, and one of my focuses was to say, “We’re not talking about racism or Black Lives Matter here. We’re here to celebrate the achievements and contributions of Black Britons and Black British culture—whether that’s from the Caribbean, Africa or wherever— in the UK”.

I also thought that we should not just focus on sportspeople and musicians, but other people like the writer and broadcaster Afua Hirsh, and the historian, writer and broadcaster David Olusoga, and other authors and politicians—the diversity of Blackness within the UK. That’s how I’ve been trying to get involved with Black History Month in Japan—by showing that there is a diverse Black presence in the UK.

What can you tell us about the history of Black people in Japan?

Beginning with the present day: first, when you look at media articles, especially in international media, and talking about Black people or mixed Black- Japanese people, there’s often a focus on issues around racism and how they are ostracised—or this constant problematising of Blackness. One thing that it leads to is a perception of constant distance between Black people or Blackness and Japan.

Whereas, I think, when looking at the histories of Black people in Japan, there’s a lot more solidarity or imagined solidarity. Whether that’s going back to the 16th century and the recently popular discus- sions about Yasuke the Samurai—a Black samurai who was accepted into Oda Nobunaga’s clan and participated in that period of history. That’s one form of connectivity or solidarity.

Or, fast-forwarding into the 19th century and early 20th century, when you have people like W. E. B Du Bois and other African American intellectuals talking about Japan in a very positive light, as being the champions of the “darker races”.

Even in the post-war period, where you have African American soldiers stationed in Tokyo, Okinawa and different places forming personal or romantic relationships—in Japan, usually with Japanese women. Okinawans, for example, felt like they’re not Japanese and so there was that opposition to the mainland.

Again, we see this solidarity, whether it’s real or imagined; there was some sort of solidarity because both Black people and Okinawans felt “othered” in some way. And so, there are all these forms of Black and Japanese connectivity, when you look into history, beyond this present day narrative of distance between Black people and Japanese people.

Going forward, and I think I can contribute to this in some way, it will be important to illuminate some of the stories of Black British and Japanese connectivity. That’s something that I’m looking forward to doing in the future.

How do UK–Japan relations tie into Black History Month?

Well, they tie into what we did with the British Embassy—speaking to a Japanese audience.

The whole time I’ve been in Japan, it gets a bit boring having to answer the question, “Where are you from?” I usually answer: “Can you guess where I’m from?” And every single time the guess starts off with America; then it’s Africa somewhere; then it’s France, Canada or Brazil. They go through every other region or country, and never get to the UK.

I think that’s really telling. It shows that, in terms of UK–Japan relations, “There’s no black in the Union Jack”, to quote sociologist Paul Gilroy’s book on the subject. That’s true whether it’s historical alliances, stories of the Brit William Adams arriving in the 16th century, Japanese leaders in the Meiji period going to the UK, or trade deals today.

And that’s Japan’s image of the UK: it has no Black life. There is no Blackness in Japan’s image of the UK, whether it’s Downton Abbey or Abbey Road; Harry Potter or Beatrix Potter; the Queen or Queen. Black Britain is hidden from Japan’s sight.

I think this speaks to that broader challenge of the UK’s public and cultural diplomacy. Britain’s diversity was celebrated at the Olympics, and there is this internal discussion about the promotion of diversity and inclusion, and yet, when it comes to outward facing activities in terms of public diplomacy, there is little focus on how we can show this multiculturalism in Britain. I think that is one of the challenges of UK–Japan relations.

And lecturing at Rikkyo University

What are your current and future plans?

I’m working on my PhD, looking at political satire in 19th century Japan. I’m also doing part-time lecturing at Rikkyo University.

One project that I hope to spend more time on after my PhD is based on a course that I developed last year, called Afro–Japanese Encounters.

For a whole term, we explored a lot of the things that we’re talking about today: the past and present, and imagining the future of Afro–Japanese and Afro–Asian connectivity. We’re looking at that with my students across different aspects: music, art and fashion. In the future, I hope to build that as my own research project.