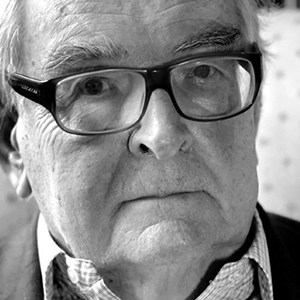

Dorothy Britton, Lady Bouchier MBE, was a bilingual poet, composer and translator. Bridging the cultures of Japan and the UK, she was so in tune with the latter that one of her mother’s friends described her as “Japanese wearing a Western skin”.

Britton, who died on 25 February aged 93, was born on 14 February 1922. She had been due to visit London in March to make a presentation to the Japan Society of the UK on her newly published memoir, Rhythms, Rites and Rituals (see page 50).

She lived in a seaside cottage in Hayama, Kanagawa Prefecture, not far from a summer villa used by the Emperor and Empress of Japan. One day, many years ago at the British Embassy Tokyo, the Empress, on learning where Britton lived, said: “So we are neighbours!”

Thereafter, from time to time the Empress would come to have tea. On one visit, the Emperor said how nice it was to hear the sound of the sea. Unfortunately, at their own villa, the thickness of the walls meant that they could not hear the waves.

Early years

Britton was born in Yokohama; the only child of Frank Britton, an English businessman, and his American wife Alice Hillier.

She was 16 months old when Yokohama was struck by the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923, surviving because her nanny sheltered her under the bed. In the aftermath, her father managed to get her and her mother on a ship to Kobe.

When she was 12, he died of a heart attack and she was sent to Claremont School in Surrey. She missed her life in Japan, saying her “happiest times … were some free periods in which I continued my study of written Japanese”.

Her mother then took her to Boston where she went to a private school and started to write poetry. After graduation they went to Bermuda to relax and, when World War II began, she was recruited by the censorship department there to work on postcards written in Japanese.

From 1943 to 1945 she studied at Mills College in California where, thanks to her proficiency in French, she was introduced to French composer Darius Milhaud, from whom she learned about musical composition.

When the war ended, she went to New York with her mother and then to London, where she remained until 1949. She was employed by the BBC and worked in the Japanese service under its head, Trevor Leggett, who was also a leading figure in British judo.

Return home

Britton and her mother got permission to return to Japan, where they regained possession of their house. Dorothy was employed in the information section of the British Embassy Tokyo, then the UK liaison mission to General Douglas MacArthur.

She was particularly amazed by the way nobody talked about the war, saying: “Everyone seemed far too busy looking towards the future to dwell on what was the past”.

She met Sir Cecil “Boy” Bouchier KBE CB DFC, who had commanded the air contingent for the British Commonwealth Occupation Force in Western Japan, and later married him.

Boy and his son Derek then moved to her cottage. In his old age, they moved to Worthing, Sussex, where Boy died in 1979. Britton immediately returned to Japan with Derek.

Creative work

Despite her peripatetic life, she found time not only to compose music, but also to write poetry and articles about Japan, also translating from Japanese to English.

Among other works, she wrote Prince and Princess Chichibu and the text for The Japanese Crane by Tsuneo Hayashida. She translated A Haiku Journey by the famous poet Matsuo Basho, and Tetsuko Kuroyanagi’s memoir Totto-chan: The Little Girl at the Window.

Her musical compositions include various suites and songs including Chinoiserie: Histoire d’un Amour Oriental for mezzo-soprano and string quartet.

Britton taught an English course for NHK and was an active member of both The Asiatic Society of Japan and the Japan–British Society, becoming a founding member of the ladies branch, the Elizabeth-kai.

For her services to Anglo-Japanese relations she was awarded an MBE in 2011.

She is survived by her stepson Derek, to whom she was devoted.