Witnessing the silent rows of downcast eyes around the meeting room after your heroic call for ideas and input can be a character-building experience in Japan. You may wonder, “How did this country get to where it is, when nobody seems to have any ideas?” Or, even, “Is my leadership insufficient to the task?”

Witnessing the silent rows of downcast eyes around the meeting room after your heroic call for ideas and input can be a character-building experience in Japan. You may wonder, “How did this country get to where it is, when nobody seems to have any ideas?” Or, even, “Is my leadership insufficient to the task?”

There are solid cultural reasons for the reluctance to contribute that is displayed by many Japanese employees, despite well-meaning entreaties by management.

For me, it is a joy to fill pages or whiteboards with ideas randomly volunteered at a meeting. But, in the case of engineers, generally I have found them to be glum, lifeless and silent. They have no ideas, volunteer nothing and just look unhappy. Often I have thought that they must lack creativity, and be a pedestrian, rather hopeless lot. It took me a while to realise that engineers are not, in fact, stupid.

I discovered that, for them, the environment was not conducive to idea generation. It could be the same for your Japanese colleagues.

Although they seemed unresponsive, the engineers were carefully analysing the issue at hand and looking for the perfect solution. In their view, in front of them was a group of loud-mouthed lightweights, talking nonsense and showing their lack of insight and knowledge. From an engineer’s point of view, this on-the-fly idea generation was meaningless.

Asking Japanese people to volunteer ideas, either in English or Japanese, is counter-intuitive, since their culture puts emphasis on group decision making, harmony, self-subjugation and modesty.

Instead, it would be better to consider what environment would be better suited to idea generation, and how we might inspire our Japanese colleagues.

In 1953, Alex Osborn published Applied Imagination: Principles and Procedures of Applied Problem-solving, which launched the “brainstorming” industry. He saw group brainstorming as an adjunct to individual idea generation.

Appropriate to this day for creating an idea-generating environment, Osborn’s four rules are:

1. Focus on quantity

2. Withhold criticism

3. Welcome unusual ideas

4. Combine and improve ideas

Much research has been done on the individual, versus the group, approach to idea generation (see Diehl, M & Stroebe, W. 1987. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53, 497–509). From my reading, I discovered there to be numerous “apples” versus “oranges” comparisons in play, making it difficult to reach concrete conclusions about the individual versus group debate.

I find that including silent, individual time for idea generation before combining the group’s ideas works particularly well for Japanese colleagues. They find it easier to bring ideas to the brainstorming session than to deliver ideas after having been put on the spot. So, publicise what you are going to work on well before a get-together.

The presence of a trained facilitator at the session also makes a difference. Sensitive to group dynamics and responsible for the processes, procedures, structures, environment, roles and ground rules, a facilitator will focus the resources of the group.

Having used idea generation with Japanese teams over the past 20 years, I have found the Japanese to be brimming with creativity and good ideas. They just need the right environment and methods in order to shine.

Conrad Heraud’s 8 Techniques of Innovative Thinking programme, and his focus mapping methodology are also excellent tools for idea generation. Starting with a broad topic, one can very quickly whittle it down to concrete, practical ideas, from which can be generated practical information.

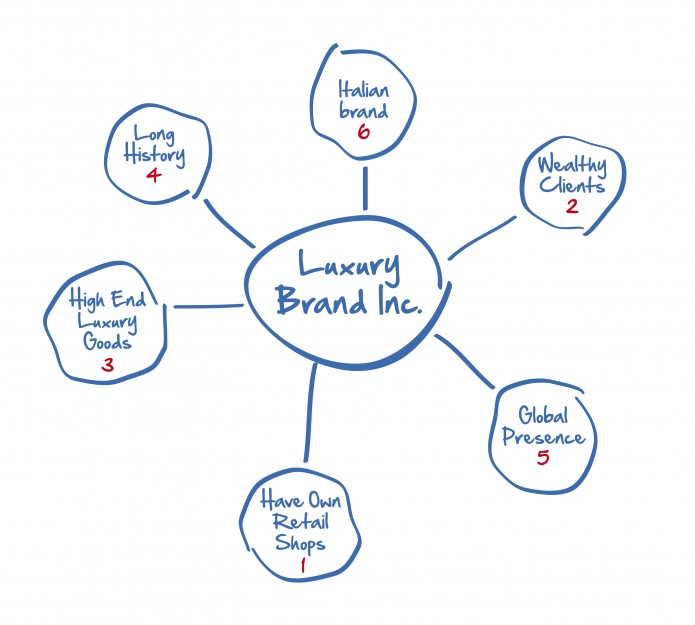

Diagram 1

In both group and individual work, it is extremely difficult to produce specific ideas directly from a broad theme. To develop concrete ideas, one must first think of the necessary information about the topic. One can’t solve a problem (or its component parts) that have not been clearly identified.

Focus mapping can best be described as a priority-cascade system, whereby a theme is written in the middle of a worksheet and then surrounded by key information. The process is very thorough and participants quickly reach the key issues regarding which concrete ideas are to be generated.

Participants should select the elements of highest priority, and continue cascading down. They should repeat the process: nominate sub-themes, suggest related information, attach priorities to the information, and proposing the next level sub-themes, until a point is reached at which ideas can be produced. This can be done with just one cascade, or three or four cascades, depending on the complexity of the theme.

Any of the priority elements nominated at any stage, can be selected as the next starting point.

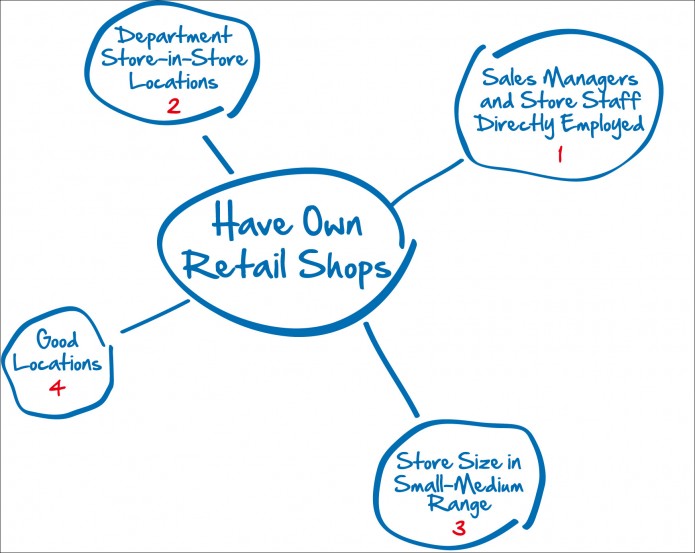

Diagram 2

Step one

Write the central theme in the centre of a piece of paper, draw a circle around it and have the participants list key information that relates to it. Many elements will come to mind, so collect as many as possible (see Diagram 1). The details and facts around the theme represent broad sub-topics in the first cascade.

Step Two

The participants should decide which Step One points have the highest-priority, and number them using a different colour (see Diagram 2).

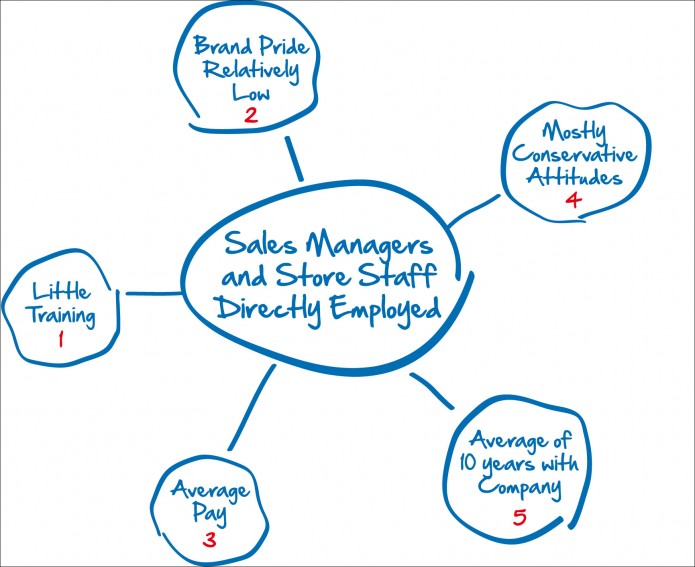

Diagram 3

Step Three

The process should be repeated on the next worksheet, using the highest-priority item and collecting as much information as possible (see Diagram 3).

Step Four

The participants may need to produce more information points depending on the subject, but usually they quickly achieve a level of detail that allows them to generate concrete ideas.

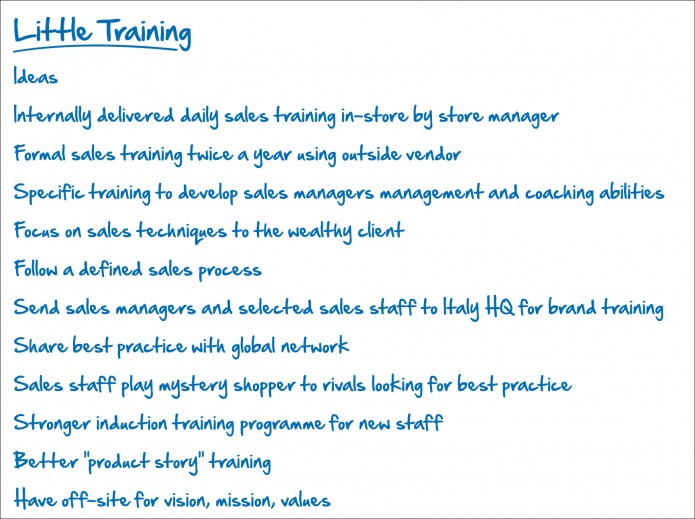

Write the highest priority point as the next worksheet’s heading. Participants should note down ideas related to the sub-theme (see Diagram 4), after which evaluating and prioritising should commence.

Step Five

Return to any of the selected priority items and repeat the process. This might be from the first page or a couple of steps into the cascade process.

The focus mapping process enables participants to quickly derive concrete data about a topic, and becomes the basis for considering practical, creative ideas. Pinpointing the priority items lends a comprehensive breadth to the process.

Diagram 4

Try it and you’ll be surprised by what your colleagues produce—even the engineers! All they need is the right environment.