Tired of waiting to secure a place for your child in one of Tokyo’s top international schools? Fortunately, year-long waiting lists could be a thing of the past as new entrants bring greater choice to expatriates and locals alike, amid a global boom in international schools that shows no sign of slowing.

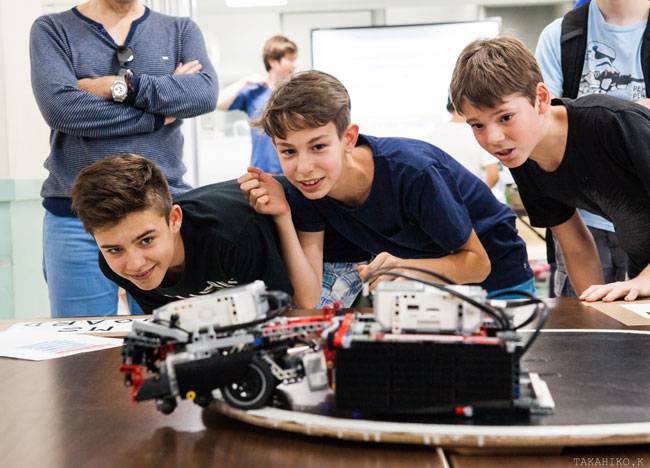

Originally created to cater solely for expatriates, international schools have surged in popularity worldwide as parents seek that edge they believe a Western education provides. From around 1,000 English-language international schools globally some 20 years ago, there are now an estimated 9,200, with the number expected to reach 16,000 within a decade, according to UK-based ISC Research.

Rather than being expatriate enclaves, some 80% of international school students are from the school’s host country.

In Japan, the number of students at English-language international schools now exceeds 12,400, up 27% from five years ago.

“There are lots of positives in being bilingual—English is one of the major international languages and going to an international school helps expand your perspective”, said Nozomi Yamazaki, a former Osaka International School (OIS) student.

Growing demand

Tokyo is listed, among other major international cities, by ISC as having at least 50 English-speaking international schools. And with new schools opening up, including Chiyoda International School Tokyo (CHIST) in April 2018 and potentially also an offshoot of London’s Harrow School, the competition is escalating for the established operators.

While schools have kept up with the increasing demand by securing staff from the UK, United States and other English-speaking nations, ISC says competition for suitable staff could intensify. The number of teachers working in international schools is expected to grow from more than 426,000 in December 2016 to 581,000 by 2021, putting pressure on recruitment.

However, if Tokyo’s existing international schools are feeling the pressure, they are not showing it, even pointing to the need for new entrants.

“We do have wait lists and we don’t want to turn people away”, said Lowly Norgate, communications manager at the British School in Tokyo (BST). “Physical space is a challenge in densely populated Tokyo, and for new international schools that are opening, the process has many required levels of approval”.

Norgate also pointed to the difficulty for new schools in securing land and even items as simple as school uniforms. However, the BST is yet to see any difficulty in securing teachers, despite its preference for teachers from the UK or other highly rated British international schools.

“Schools have to offer an attractive package for anyone coming from overseas”, she added. “We feel very strongly about getting the best teachers … we insist on seeing them teach in their own schools before confirming any appointment”.

Japan’s oldest international school, Yokohama’s Saint Maur International School, also says recruiting teachers to Japan is not a challenge, given the nation’s attractive global reputation.

“We don’t have any problems attracting high-quality teachers to our school”, said secondary school principal, Timothy Matsumoto. “When I talk to people about why they chose Japan, they talk about safety. It’s a very safe country, people are very polite as well, and there’s a certain sense of timeliness that is unmatched”.

New kids on the block

Another British-style school is Clarence International School in Minato Ward, which was founded in 2016 based on the English early years foundation stage framework.

Co-founder Fei-Fei Hu said recruiting teachers was not a challenge for the art-focused nursery, which has developed its teaching materials in collaboration with Children & The Arts, a charity established by Charles, the Prince of Wales.

“When we opened [in 2016], we received more than 500 applications for our teaching positions”, Hu said. “Going forward, we would like to recruit senior teachers from the UK, with the help of our partner, The Prince’s Foundation”.

Hu and his wife Ayahi have bigger plans for the institution, however. They include expanding the school premises and developing a “Clarence Lab” in Tokyo and London to broaden the school’s curriculum.

In July, Hu was appointed Japan strategy adviser for the prestigious Harrow School, which already has international schools in Bangkok, Beijing, Hong Kong and Shanghai.

Michael Farley, headmaster of Harrow Bangkok and leader of Harrow’s Japan project, said Harrow was “currently investigating a number of possible sites in both the Kanto and Kansai regions, though would still be receptive to other opportunities”.

Another new entrant, CHIST, says it plans to “apply Buddhist ideals to the cultivation of well-educated, internationally minded and engaged individuals”. Located in Chiyoda Ward, the co-educational school, operated by the Musashino University Educational Foundation, plans to offer “an advanced primary and secondary educational curriculum”.

CHIST’s primary school is expected to open in April, followed by a middle school and high school in April next year.

Keeping ahead

Perhaps with an eye on the new competitors, Saint Maur is planning new investments this year in sporting facilities, something that has even greater impetus given the upcoming Tokyo 2020 Olympic and Paralympic Games and 2019 Rugby World Cup. And in any case, those events are driving demand even higher.

“We’ve seen more enquiries from people connected with the Rugby World Cup and the Olympics—not just those in sport, but also administrators, legal teams and other staff”, Norgate said.

The recent move by the Tokyo Metropolitan Board of Education to make English-speaking tests mandatory for high school entrance exams could see even more demand for English-language education from Japanese parents. This is even though they are legally required to send their children to Japanese schools regulated by the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology.

For Tokyo’s international schools, the city’s increasing population of non-Japanese residents together with local demand should point to a bright future, with events such as the Olympics highlighting the need for an English-language education.

“Because of the Tokyo Olympics, the Japanese people will finally realise that they need to have more people speaking English in Japan”, said Yamazaki, the former OIS student. “I grew up in a bilingual environment and I’m 100% sure I want my kids to be the same”.