What a trade pact means to Britain, Japan and the EU

After years of tough negotiations, the European Union and Japan at last agreed in Brussels on 28 May to discuss a free-trade deal that would link the world’s largest market with the third-biggest economy.

The deal—whether it’s called a free trade agreement (FTA), economic integration agreement (EIA) or economic partnership agreement (EPA)—could bring more than €54bn into Europe from Japan, and an estimated €43bn in extra trade to Japan from the EU, with a significant proportion of that coming from the UK, where bilateral trade with Japan was worth about £18 billion in 2009.

British Ambassador David Warren told ACUMEN that the agreement is “excellent news”.

“The opportunities on offer from an EIA would be really significant, not just for Japanese business gaining better access to the enormous EU market, but for European business, too.

“Tackling non-tariff barriers as part of the negotiations would open up to more EU firms important markets in Japan, such as life sciences and government procurement”.

On a visit to Tokyo, Secretary of State for Business, Innovation and Skills Vince Cable said: “An EIA will offer major opportunities for Japanese business in the EU, but some change will be needed here as well, to make the Japanese regulatory environment more open”.

A British embassy spokesperson said: “The prime minister, at the March meeting of the European Council, made it clear that we are in favour of an FTA and we think the possible benefits are considerable. We look forward to the next stage in reaching this ‘deep and comprehensive free trade agreement’—including tackling some of the outstanding issues, such as non-tariff barriers”.

Nikolaos Zaimis

EU Ambassador Hans Dietmar Schweisgut told ACUMEN: “The summit was probably the most important one we have seen. Concrete areas of cooperation—from nuclear safety to renewable energy and research—will be reinforced by the political commitment to work towards a comprehensive EPA. We now have to make full use of the scoping exercise to define our joint vision for an ambitious and balanced agreement”.

The previous EU-Japan Summit, held in Tokyo in April 2010, entrusted a joint High-Level Group with identifying the options for strengthening all aspects of the bilateral relationship and defining the framework for implementing those improvements. Based on the reports from the group, the EU and Japan announced in Brussels that they believe the time is right to put into action the process for parallel negotiations on achieving two outcomes.

The first would be a “deep and comprehensive” FTA, EIA or EPA that addresses all issues of shared interest on both sides, including tariffs, non-tariff barriers, services, investment, intellectual property rights, competition and public procurement.

The second outcome would be a binding agreement covering political, global and other sector-specific cooperation. It would be “underpinned by their shared commitment to fundamental values and principles”, the leaders said.

In their joint statement, the two sides committed themselves to launching preparatory discussions “at the earliest possible time”. When the EU and Japan have reached agreement on the specific fields that will be covered by the envisaged trade deal negotiations in the preparatory talks—which the EU refers to as a “scoping exercise”—formal talks will commence.

The understanding reached in Brussels is only the start of what will be a highly exacting and painstaking process, but Nikolaos Zaimis, first counsellor and head of the trade section at the Delegation of the European Union to Japan, told ACUMEN that the situation has moved on “enormously” since last year.

“The start of that process was the EU entering into an FTA with South Korea that comes into effect in July”, he said. “That created the momentum on the Japanese side because they probably feel some pressure in the electronics and cars sectors”.

The FTA with Seoul will gradually eliminate all tariffs—which were previously 10% on cars and 14% on electronics—on imports from South Korea. Those two sectors are also of vital interest to Japanese industry and they fear competitive disadvantages, Zaimis said.

The 13th EU-Japan Business Round Table, entitled “EU-Japan Business Cooperation: Growth for the Future”, was held in Rome on 28-29 April.

“One big issue that Japan very clearly wants is to eliminate tariffs and level the playing field with South Korea, but it was not clear what we would get in return”, said Zaimis. “The EU was not really worried about Japanese tariffs as most of our issues with Japan concern non-tariff and regulatory issues. The thinking process in Brussels was: How would it be possible to bring the two different ideas together?”

The EU is using the South Korean FTA as a model for future trade deals and wants the agreement with Japan to cover a wider range of economic issues—services, procurement, the environment, customs issues and so on—but added to the mix here is the Joint Action Plan of 2001, which has served as a framework for cooperation and dialogue.

With that deal due to expire this year, the EU wants to combine the two agreements and take the relationship “to a new level”. A similar model is being applied by the EU in discussions on ties with Canada and, it is hoped, will in the future be applied to talks with India.

Despite wanting the trade deal, Japan has been hesitant about the political alliance that Europe proposed.

“There was some concern, on the Japanese side, about this idea, because they do not have such political agreements”, said Zaimis. “We explained that we share the same values; we are both democracies and support human rights, labour rights and so on; and that this could all be put in the document. Since we are strategic partners, moreover, we should not focus solely on trade issues”.

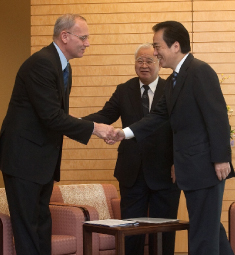

EU-Japan Business Round Table co-chairs Jean-Yves Le Gall and Hiromasa Yonekura meet Prime Minister Naoto Kan in January.

Previously, four pilot projects had been launched to test whether it would be easy to deal with regulatory issues in Japan. The outcome was not as good as had been anticipated.

“After one year of discussions, we saw that changing regulatory issues is not that easy, and not as fast as had been expected”, said Zaimis. “The positions of EU member states and businesses are very important. At first, many were very reluctant because changing regulations was not at all [straightforward] and they feared they would get little out of the deal or that the talks would never end”.

Some sectors were completely opposed—notably the auto industry—as it would mean Europe would give up its tariff protection for Japanese imports, but had little to gain from a declining Japanese market. The same concerns were expressed during the discussions on the FTA with South Korea, which resulted in a safeguard mechanism being included in the final agreement that will not permit a surge in imports of South Korean cars. A similar clause is likely to be included in the Japanese agreement.

The sectors that said they were in favour of the deal with Japan were the food industry, agriculture and semi-processed products, and pharmaceuticals. More worrying to Brussels was the vast majority who were silent on the issue.

“A lot of industries are more interested in emerging markets and have little time to spend on Japan because of the perception that Japan is a difficult market”, said Zaimis, adding that as some of the issues are regulatory, firms are asking whether it is worth the time, money and effort when they could go to China, which has fewer problems and where they can make more money.

“But over the past 12 months, some firms have become more favourably inclined to an FTA with Japan”.

“What has changed more dramatically is the position of some member states,” he said. “Some were very sceptical, but now they have very clearly come out in favour of an FTA with Japan, because this is too important a request to turn down and Japan is too important a partner to ignore.

“Not all member states are in favour, but some of the key ones are”, he added.

But, perhaps, most important is the fact that the change in Japan shows the way it has done business in the past cannot be relied on for the future development of the nation.

“This has come about because there has been a lot of change in Japan and globally, with a lot more trade strength in the multi-polar world,” a spokesman for the British Embassy Tokyo said. “It makes a lot of economic sense in Japan to underline how important it is for countries to trade freely with each other.

“What is striking is how Japan has suddenly seen this as important, rather than just assuming the country can go on as it has been doing”, he added. “It reflects a change in Japan and about where its future lies. Japan can’t just rely on the old model any longer, and this will benefit Japanese firms as well”.

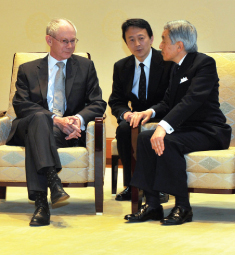

European Commission President Jose Manuel Barroso and European Council President Herman van Rompuy met Emperor Akihito on a visit to Tokyo for a summit in April 2010.

“This is a severe barrier not just for European businesses wanting to sell their medicines in Japan, but also for Japanese firms, for which numerous approval processes make new medicines more expensive than they need be, reducing their ability to compete overseas”.

In 2009, Japanese exports to the UK were valued at about £10 billion, while the UK sold Japan goods or services worth more than £8 billion.

There will inevitably be bumps in the road to completing the EU-Japan trade agreement, but the decision to proceed taken in Brussels is a very positive step forward, as Europe would not have agreed to make that undertaking if there had been a chance that the FTA would get bogged down in discussions, as are talks on trade deals between Japan and both South Korea and Australia.

“FTAs with developed countries have to be well prepared to avoid a situation in which they get stuck in a couple of years”, said Zaimis. “We want to avoid that situation.

“Also, it would send a bad image to the rest of the world if the two biggest economies cannot reach a trade agreement”, he added. “The future of trade policy and liberalisation in the world would be at risk and we have some responsibility, as members of the [World Trade Organization], to be successful”.