Despite strong bilateral alliance, ties may be weakening

The British Council has released a research report entitled “The Cultural Relationship between the UK and Japan”, which is one of a series from around the world. The research is based on a mixture of statistical indicators, an on-line survey, and in-depth interviews with key individuals involved in the bilateral relationship.

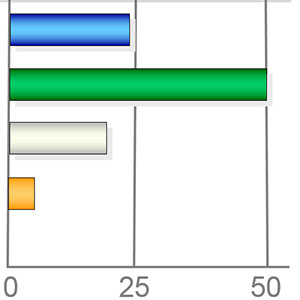

The report’s conclusion is that the UK-Japan cultural relationship is, for the most part, in good shape. Just under two-thirds of Japanese respondents ranked the UK among the top five countries in terms of benefits for Japan of closer engagement, while 27% put it in the top three. Bilateral political and diplomatic links are strong, and there are very few issues about which Tokyo and London strongly disagree. There is a notably high level of collaboration in the arts, with a strong appetite for close cooperation in other sectors, including education and civil society.

The report’s conclusion is that the UK-Japan cultural relationship is, for the most part, in good shape. Just under two-thirds of Japanese respondents ranked the UK among the top five countries in terms of benefits for Japan of closer engagement, while 27% put it in the top three. Bilateral political and diplomatic links are strong, and there are very few issues about which Tokyo and London strongly disagree. There is a notably high level of collaboration in the arts, with a strong appetite for close cooperation in other sectors, including education and civil society.

Opportunities for grass-roots exchange, however, are limited by the sheer distance and expense of travelling between the two countries, as well as the language barrier, which serves as a significant constraint on closer engagement.

Meanwhile, there are worrying signs that the relationship may be weakening. The often-noted “inward-looking” tendency of young Japanese people is affecting relationships with all countries, of course, not just the UK. The number of Japanese students going overseas, for instance, is falling — and much more sharply than the decline in the population of student age. Although this fall is also likely to be due in part to the weaker economy, one interviewee put it: “In [Japan], everybody’s talking about globalisation. But the actual trend is the reverse”.

Japan and the UK are natural friends and partners and the cultural relationship between the two countries is a good one.

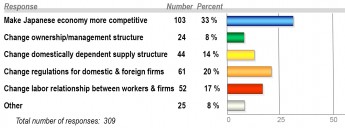

Another factor behind the perceived weakening of the UK-Japan relationship is Japan’s increased focus on neighbouring countries such as China and South Korea. This is a trend affecting the business sector, among other areas. One Japanese comment was: “We are putting more emphasis on relationships with Asian countries. The interest in Japan among business people in Europe is declining.”

The UK is also being criticised: its commitment to Japan has been reduced. However, during his visit to Japan in July, Foreign Secretary William Hague expressed a clear determination to reverse this situation.

The growing perception of the EU as a political entity is ambiguous in its implications for the UK. One comment was: “Given that Europe is in the process of becoming a joint entity in the form of the EU, I don’t think there is much benefit from a political and diplomatic point of view in strengthening relations just with the UK”.

On the other hand, the UK is seen by some as the ideal intermediary between Japan and Europe. “Whenever we think of Europe, we think of the UK, which is ironic as the UK doesn’t always think of itself as being in the EU. We feel that within the EU, the UK is the one that understands our issues the best”. So there is perhaps scope for the UK to play a more active role in Europe, and indeed in the cultural sphere; the British Council plans to do so, having recently taken over the chair of the EU National Institutes of Culture (EUNIC), the umbrella body of European cultural institutions in Japan.

While overall, the report suggests a friendly and constructive relationship between the two countries, it urges us not to be complacent. It concludes: “Japan and the UK are natural friends and partners and the cultural relationship between the two countries is a good one. But we must be careful that we don’t take this friendly relationship for granted. It needs working on”.