Hugh Cortazzi was born in 1924, and educated at Sedbergh School in Yorkshire, where his father was a teacher. In 1941, he won a scholarship to St Andrews University to study Modern Languages but volunteered after five terms to join the Royal Air Force (RAF), and was sent to the School of Asian and African Studies (SOAS), London University, to learn Japanese.

Hugh Cortazzi was born in 1924, and educated at Sedbergh School in Yorkshire, where his father was a teacher. In 1941, he won a scholarship to St Andrews University to study Modern Languages but volunteered after five terms to join the Royal Air Force (RAF), and was sent to the School of Asian and African Studies (SOAS), London University, to learn Japanese.

In January 1945, he was posted to India and began to take part in the interrogation of Japanese prisoners of war. Later that year, after the Japanese surrender in August, he moved to Singapore, where he joined the war crimes investigation team. He spent a year in Japan with the RAF, before returning to SOAS, where he took his degree in Japanese in 1949, the year that he joined the Foreign Office.

Hugh Cortazzi with his wife Elizabeth outside their home

He was posted first to Singapore to join the office of the Commissioner-General for South-East Asia, Malcolm MacDonald, but after a year he was sent back to Tokyo for his first tour of duty at the British Embassy Tokyo, where he was involved in negotiating the United Nations Status of Forces Agreement. He returned for a home tour to London, where among other things he was required to interpret for Prime Ministers Winston Churchill and Shigeru Yoshida on the occasion of the latter’s visit to London in October 1954.

In 1956, he married his Foreign Office colleague Elizabeth Montagu, with whom he had been serving in the Information Research Department; a posting to the British Embassy in Bonn followed, from 1958 to 1960.

Major investment

Hugh’s real diplomatic involvement with Japan began in 1961, with his second posting to the British Embassy Tokyo. He was to spend most of the 1960s in Tokyo (with a short period back in London in 1965–6).

From 1961 he was the head of the political section in the embassy. This was the period in which bilateral discussions at foreign minister level began between Lord Home and Masayoshi Ohira; the Anglo-Japanese Treaty of Commerce and Navigation was concluded in 1962; and HRH Princess Alexandra paid the first post-war royal visit to Japan.

Japan was now well set on its phenomenal period of economic growth and re-entering the international community with the 1964 Olympics. Hugh returned to Tokyo in 1966 as commercial counsellor and re-organised the trade promotion effort within the embassy. He tackled the trade barriers that were then prevalent, encouraged British firms to adopt a less condescending and protectionist approach towards Japan, and prepared for the major British Week promotion in Tokyo in 1969 that was opened by HRH Princess Margaret. As he wrote in his memoir, Japan and Back (1998), “We were able to record a significant increase in British exports in 1969 and for the first time that year our exports to Japan and our imports from Japan were in balance”.

Hugh spent the 1970s out of Japan. From 1972 to 1975 he was minister (commercial) in Washington. He returned to London as the deputy under-secretary in the Foreign & Commonwealth Office dealing with Asia, a post which of course involved contact with Japan. However, much of his time was spent on other responsibilities, not least the aftermath of the war in Vietnam, and China’s beginning to emerge from Maoism. For two years, he was also chair of the Diplomatic Service Association, the senior diplomats’ trade union.

He wondered if he would ever be able to return to Japan, but the opportunity came with the retirement of Michael Wilford in 1980, and Hugh became ambassador in October that year.

Hugh served in Tokyo for three and a half years: as was then the rule, he retired on his 60th birthday. By far the most significant part of his ambassadorship was his work to promote trade and attract Japanese inward investment, then in its infancy. He helped to pave the way for the major investment by Nissan Motor Company in Sunderland, formally announced after his ambassadorship in 1984. He had overseen, at the Tokyo end, the process by which then-President Shintaro Ishihara’s letter of intent had been transformed into a firm commitment.

Many other investments were made during that period, not least that in 1983 by NEC, which invested in a factory in Livingston, Scotland, that was opened by the Queen. Japanese firms that opened plants include Maxell Holdings, Ltd.; Ricoh Company, Ltd.; Sharp Corporation; Brother Industries, Ltd.; GS Yuasa Corporation; Yamazaki Mazak Corporation; Hitachi, Ltd. after the break-up of their GEC joint venture; and the ICL–Fujitsu relationship. Discussions also began with Honda Motor Company, Ltd. and Toyota Motor Corporation.

Trade promotion efforts continued to intensify, as did attempts to get the Japanese to remove trade barriers and bureaucratic obstacles. Hugh was as frustrated by the difficulty of overcoming Japanese bureaucratic rigidity as he was by British firms not always using the breathing space afforded by the voluntary arrangements that were negotiated to improve their productivity and competitiveness.

Scholar and writer

It was not the easiest time politically. The British efforts to develop closer political cooperation did not secure the Japanese government’s support during the 1982 Falklands War. A pro-Argentine lobby in the Diet was able to influence opinion because of fears over the impact of a pro-UK stance on Japanese communities and trade in South America.

A visit to Japan by Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher in September 1982 was difficult: she attacked Hugh and other officials at considerable length for not taking an even more aggressive line against Japan over trade restrictions, he refused to back down, and eventually everyone went to bed, with Hugh telling his wife that he would probably have to resign the next day. “In fact”, as he later wrote, “it all worked out quite satisfactorily in the end and she stuck to her brief”.

Hugh Cortazzi seated on then-Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s left at Fujitsu Fanuc Ltd. in 1982.

Hugh retired from Tokyo and the Diplomatic Service in May 1984. Having been created KCMG in 1980, he was advanced to GCMG on his departure from Japan. Thirty five years as a diplomat were to be followed by an astonishingly productive 34 years of notional retirement, as a scholar and writer about Japan. He also took on a number of non-executive roles, including with Austin Rover, Hill Samuel, and later some Japanese firms, including NEC, the Daiichi Kangyo Bank, the Bank of Kyoto and department store Mitsukoshi. He chaired the Japan Society from 1985 to 1995, and was an important participant in the preparations for the Japan Festival (chaired by Sir Peter Parker) in 1991, which marked the society’s centenary. He attended meetings of the UK-Japan 2000 Group (now the 21st Century Group) and was an instigator of the UK-Japan High Technology Forum.

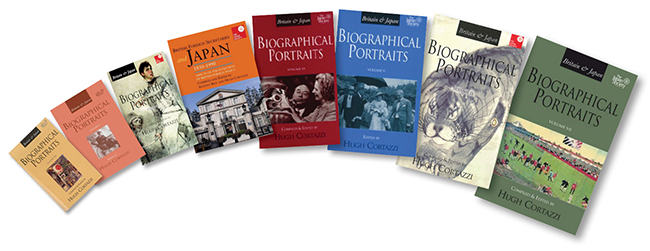

A selection of Hugh’s books

On top of all this activity, he produced book after book on Britain and Japan—biographies; monographs; general studies of modern Japan, Japanese culture and history—and contributed to and co-edited collections of essays about the historical links between the two countries. The 10-volume series, Britain & Japan: Biographical Portraits, much of which he edited personally, is a formidable achievement. He launched his most recent book, co-edited with Antony Best, British Foreign Secretaries and Japan 1850-1990, only a few weeks ago, at the AGM of the Japan Society in London. A volume on royal and imperial links, on which he was still working at the time of his death, will be published in 2019.

Hugh Cortazzi with Crown Prince Naruhito (centre) in 1985.

Many tributes have been paid to Hugh since his death, both in Britain and Japan. He was the foremost Japan specialist of his generation in the Foreign Office. He was an inspiration to many others, both as a diplomat and as a scholar. He epitomised the virtues of both diplomacy and scholarship—industry, expertise, objectivity, truthfulness—and he never stopped working, writing, learning, and pushing for a better bilateral understanding. We mourn him for all those reasons. But many of us also mourn him as a friend, and our thoughts are with his wife, children and grandchildren.