Radical Shakespeare rework reflects modern Japan and its problems

- Adaptation set on stunning Sado Island

- Noh masks, dramatic scenery, sheer cliffs, primal forest

- Big-screen debut held in Shibuya

Welsh filmmaker John Williams has taken one of William Shakespeare’s most well-known plays, turned it upside down, inserted a Japanese rock-and-roll band, and set it 30 years in the future and on remote Sado Island in Niigata Prefecture.

The film is such a radical departure from the Bard’s work that it is not at all certain that he himself would recognise it as an adaptation of The Tempest.

“It has taken a long time to turn the original idea into the rather strange beast that it has become”, Williams admitted at a discussion of Sado Tempest the day before the film’s big-screen debut on 16 February at Shibuya’s Eurospace cinema.

The Japanese-language film—which has English subtitles—is set entirely on Sado Island, and weaves into the storyline the traditional culture of the former place of exile. As well as incorporating oni-daiko—a traditional religious masked dance-drama of the island that is believed to ward off devils as well as be a prayer for a bountiful harvest—together with Noh masks and lyrics, the film makes the most of the isle’s dramatic scenery, from the ruins of a gold mine to the sheer sea cliffs, the primal forest at the heart of the island and the abandoned Sensoji temple.

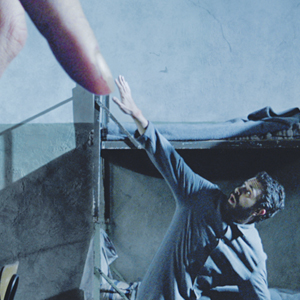

However, the story begins far removed from the island. The always-angry frontman (Juntoku) of a four-piece punk band (Jitterbug) collapses on stage and all are transported to the island for crimes against the state.

Imprisoned and forced to pan for gold by the warden, they are told they can never escape their exile. The storyline takes a turn with the arrival of a mad woman (Miranda), who repeats lines from Noh plays. She is the daughter of a scientist (Omuro), who had previously come to the island to carry out experiments, but who had doomed the island to permanent winter after a storm had destroyed his secret genetic laboratory.

Juntoku escapes from the prison, begins to put Miranda’s poetry to music, and roams the forest in the heart of the island, meeting cannibals and demons along the way, and even Omuro. But there is a final twist in the tale.

The parallels between Shakespeare’s version of events and the film that Williams has produced are clear, although the differences are stark.

Invited by the local film commission to set a film on the island, Williams said he was stunned by the “astonishingly beautiful” scenery but baulked at the idea of making a promotional film that revolved around the crested ibis that are slowly being returned to the wild.

Instead, Williams said, he was far more interested in the island’s history as a penal colony and, in particular, Emperor Juntoku (1197–1242)—who shares his name with the lead character in the film and was banished to Sado in the 13th century for plotting to overthrow the Kamakura shogunate.

“I was very interested in his story, about his exile there in 1242 and his death at the age of 46, although it is said that he achieved enlightenment before dying”, Williams said. Thus, the tale of an exiled artist was applied to a rock band similarly detached from mainstream society.

The Noh lyrics were inspired by another of the island’s famous exiles, the Noh playwright Zeami Motokiyo, who did his best work during the early 1400s.

“There were a lot of hurdles in terms of the material. I went to Sado about 20 times over three years before we were able to start filming in March 2011”, said Williams, who has lived in Japan since 1988 and teaches film and translation at Tokyo’s Sophia University.

“I loved all the cultural history that had been left [on Sado Island], and that it was different from the rest of Japan. There was a palpable sense of being different and, in some ways, odd”, he said. “It was the thorny otherness of the island that I liked”.

Williams, who won critical acclaim for his first two Japanese-language feature films, Firefly Dreams (2001) and Starfish Hotel (2007), admitted that he had problems, at times, superimposing elements of the original Tempest with his own interpretation, but he is satisfied with the final outcome.

“I had wanted to turn [the story] on its head and ask a lot of ‘what-ifs’”, he said. “The outcome is something of a hybrid film, an odd hybrid creature, but I’m happy with that.

“This is a film about Japan now, not just a Tempest adaptation. It is also a reflection of what is going on in Japan today, and some of the problems that we have here at the moment”.