Gaming could be here in two years, despite social fears

• Create jobs and provide skills

• Help finance quake rebuilding

• Attract wealthy tourists

• Boost ailing economy

At a packed press conference in Miyazaki on 3 April, Hajime Satomi, chairman and president of Sega Sammy Holdings Inc., added his considerable weight to a debate that has been bubbling for more than a decade. But the deliberation has acquired added significance as the enormous cost of rebuilding the Tohoku region has become apparent.

Announcing the completion of his firm’s ¥400mn purchase of Pheonix Resort KK, operator of the Seagaia water park and resort, Satomi was asked whether his plans for the facility include a casino.

With a nod and a smile, he agreed that Seagaia “must have a casino because it will attract lots of visitors from Asia and create jobs”.

“As a matter of course, we would like to bear in mind the possibility”, he said. But he did point out that there is one major stumbling block preventing roulette wheels from spinning and poker hands from being dealt: casinos are illegal in Japan.

With Satomi’s confirmation, the head of one of Japan’s largest amusement and entertainment firms sided with gaming tycoon Kazuo Okada, whose pachinko company Universal Entertainment Corp. in January started work on a $2bn casino and hotel complex in the Philippines’ capital of Manila.

International casino operators—including British firms—have given hope to the millions of Japanese who enjoy a flutter at the tables and foreign visitors who might feel likewise.

Most significantly, those pushing for laws banning casinos to be rescinded have the support of 150 Diet members from six parties across the political spectrum. The group, headed by Issei Koga of the Democratic Party of Japan, had hoped to have the legislation enacted in the previous session of the Diet, but time ran out. Rewriting the rules will not happen overnight, they caution, but the process could be under way in as little as two years.

The pro-casino group warn that failure to seize this opportunity could prove a serious blow to Japan’s already ailing tourism industry and fundamentally affect the national economy.

“Neighbouring areas are contemplating similar plans, so if we do not hurry we may miss a major opportunity”, Takeshi Iwaya, a member of the opposition Liberal Democratic Party and key supporter of the campaign to legalise casinos, was quoted as saying by media in late February.

Nicole Fall says the future is already here—with online gaming.

“It would be an engine for fiscal revival and job creation that would not depend on raising taxes”, he told Bloomberg.

Tax hikes and rebuilding the shattered north-east of Japan have been, arguably, the biggest issues with which the government of Prime Minister Yoshihiko Noda has had to grapple since the Great East Japan Earthquake.

Estimates of the cost of rebuilding have been as high as the yen equivalent of £158bn and, with Japan still struggling to emerge from an economic slump that has dragged on since the early 1990s, there have been few realistic proposals of ways in which to fund the recovery. Further, this comes on top of underlying problems related to a shrinking working population, decreasing tax contributions, and a growing elderly population that is consuming the state’s income in the form of pensions and healthcare costs.

The government has submitted a proposal to the Diet to raise the consumption tax in two phases, from the present 5% to 8% in April 2014, and then to 10% in October 2015.

Predictably, the backlash against the plan has been swift and strong: polls indicate that more than 70% of the electorate oppose the increases; the opposition parties have condemned the proposal; and there are dangerous rumblings of discontent within the ruling party.

And while they might not be an immediate panacea for all Japan’s ills, supporters of a change in gambling legislation here believe that casinos offer more positives than negatives.

According to a 2009 study by Ryosaku Sawa, a professor of economics at Osaka University of Commerce, a domestic casino industry could rake in ¥3.4trn a year, as well as a healthy injection of tax revenues for both local authorities and the national government.

And as a simple indicator of the potential demand for casinos here, Japan is already home to 12,000 pachinko halls with some 5mn slot machines—five out of eight slot machines in the world.

Reportedly, intense behind-the-scenes lobbying is underway by domestic and international gaming firms. In addition, Sheldon Adelson—the Las Vegas gambling mogul behind the hugely popular Marina Bay Sands resort in Singapore—recently visited Japan and South Korea to state his case for a relaxation of the rules.

Reportedly worth $26.8bn, the 78-year-old Adelson told a conference in Tokyo that Japan “would benefit” from casinos modelled on his Singapore operations.

The evidence would seem to bear out that conviction, at least on the financial side.

The Marina Bay Sands opened in April 2010, two months after Genting’s Resorts World Sentosa welcomed its first gamblers, and the two casinos reported combined revenues of $6bn in 2011. For the government, that translates into serious tax revenues.

The figures are equally eye-popping in Macau, which has 34 casinos and earns the government an estimated $13bn a year.

Aware of the pulling power of Asia’s equivalent of the Las Vegas strip and the vast pool of newly rich Chinese, Adelson’s latest venture, the 279-m2 casino at Macau’s Cotai Central resort opens in April, with 6,000 hotel rooms and waterfalls cascading through the lobby.

The UK may lack a city as synonymous with gambling as Macau or Las Vegas, but a number of firms with operations in the UK are also monitoring developments in Japan—although they are playing their cards very close to the chest about specific plans.

Among the best-known names in the industry in Britain is the Rank Group, which operates 35 clubs in the UK and reported revenues of £238.6mn in December 2010, up more than £18mn on the previous year.

The Hard Rock group operate a casino in London, while the Las Vegas-based Caesars Entertainment have a foot in the door of the UK market, and Malaysia’s Genting Group operate 45 casinos in Britain—from Edinburgh to Plymouth and including Crockfords, the world’s oldest private members gaming club, located in Mayfair.

None of the firms contacted for this article would comment on their firms’ potential interest in the Japanese market, but a spokesperson for the National Casino Industry Forum told BCCJ ACUMEN that, “All these companies have a close eye on every potential new market”.

As well as these firms, areas that might host the first casinos are jostling for position.

Tokyo Governor Shintaro Ishihara has been a strong supporter of a change in the legislation, with a spokesman for the metropolitan government telling BCCJ ACUMEN: “Tokyo believes that casinos can be a resource to attract more people to the city, help the economy of the city and create more jobs. That is the effect we are hoping to achieve”.

Okinawa has been proposed as another potential location for gaming facilities.

“The national government is stepping forward finally to consider changing the law, and Okinawa would be interested in finding out more about the possibilities”, according to Shigenobu Asato, chairman of the Okinawa Convention and Visitors Bureau. “We are open to all ideas and opportunities, although we do have to take into account the feelings of local people about this sort of plan”.

The authorities are also acutely aware of the need to keep Japan’s organised crime groups well away from the industry—one that they would immediately recognise as being potentially lucrative—and there are also other concerns.

“In Singapore and Hong Kong, the casinos are primarily a tourist attraction”, said Roy Larke, a professor of Japanese business and international marketing at Rikkyo University. “I don’t have the figures, but my guess is that the majority of visitors to Tokyo—even to Tokyo Disneyland—are domestic.

“A casino business, to be really successful, would need a very high proportion of international—notably Chinese—tourists”, he said. With Macau on their doorsteps and able to gamble in their own language, Chinese gaming tourists would probably opt for somewhere closer to home.

“If this problem were not solved, then the casino business would probably simply end up as little more than a new off-shoot of the pachinko parlour industry, catering entirely to locals in a shady, legally accepted but grey area”, he said. “In that case, I don’t personally see the point”.

Another issue is the availability of online gaming, says Nicole Fall, the British founder and trend director at Tokyo-based Five by Fifty, an Asian consumer trend and strategic research agency.

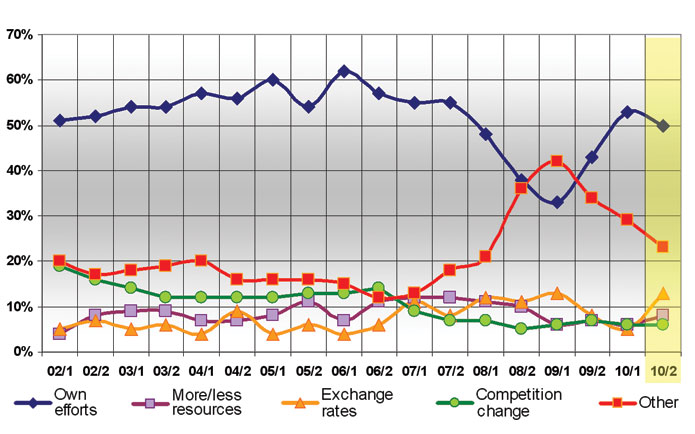

“I don’t feel the future is physical casinos per se”, she said. “In fact, the future is already here in terms of gambling. Social gaming in Japan was worth upwards of $1.43bn in 2010, with 37% of all gamers having spent money on a game.

“Who needs a physical space when most consumers are already digitally connected and want to consume, entertain themselves and connect online?”

Still, supporters of new legislation are clearly gaining momentum and the government cannot help but be enticed by the potential windfall.

The smart money is riding on when—rather than if—Japan will legalise casinos.