For parents in Japan seeking an international education for their children, Europe—the UK in particular—has been the destination of choice for decades.

But that may be changing. To find out why ACUMEN spoke with education experts and insiders to get their thoughts on recent industry trends, as well as the increasing appetite for international schools with boarding as an option in Japan and the Asia–Pacific region.

New dragons

For the first time in Japan, a European- and British-style boarding school experience for primary school children will begin in 2020.

In spring of that year, Jinseki International School (JINIS) will open in Jinseki-gun, a remote mountainside location in Hiroshima Prefecture.

Headmaster Nicholas Gunn said that the not-for-profit school will seek to raise the bar for education in Japan. The school will not only deliver a European- and British-style boarding school experience, but also take advantage of its remote countryside location.

“We will be able to look at things from a theoretical perspective in the classroom, and then take it outdoors—on camping trips, for example—so that the children can live and breathe what they learn in a textbook or on an interactive whiteboard”.

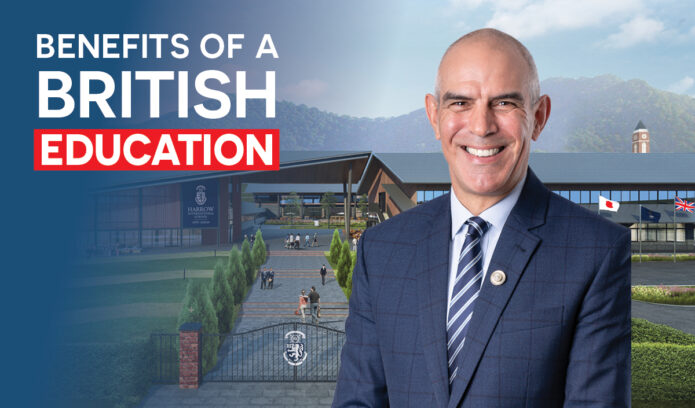

John Baugh

To achieve its goals, the school is tapping the collective wisdom of two titans of the British boarding school system: John Baugh and Michael Robert Gray.

Baugh is the former headmaster of the Dragon School, a co-educational boarding school established in Oxford in 1877.

Michael Rob Gray

Gray has been the deputy head and director of academics at Institut Le Rosey, a North American and European-style boarding school established in Rolle, Switzerland, in 1880.

Both have advised Next Education Development Environment Inc. (NEED), a subsidiary of internet advertising company News2u Holdings Inc. NEED is the parent company of JINIS.

A dual-language, English–Japanese international boarding school, JINIS will have a focus on grades one to six and will offer the UK’s national school curriculum, Gunn said.

The school will offer the same hours of education as do domestic schools, including for the study of Japanese. This is in line with its accreditation as an Article 1 school, a definition under Japan’s Basic Education Act—legislation which falls under the remit of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT).

JINIS is located in the remote mountainside of Hiroshima Prefecture.

Canadian schooling

JINIS is creating waves in the education system in Japan. But offering an international boarding school experience is not entirely new here.

Columbia International School (CIS), for instance, opened its doors way back in 1988.

Based in Saitama Prefecture, CIS offers the Ontario Curriculum, from the Canadian province of the same name. The school enrols children—from kindergarten through grade 12 and offers boarding to those in grades nine to 12.

Barrie McCliggot

When CIS opened, there was not a lot of choice for international education in Japan, Barrie McCliggot told ACUMEN. McCliggot is the principal of CIS.

“That was really how the dorm got built in the first place. And around that time —25 years ago—was when we added the junior high school”.

Thirteen years ago, CIS began offering elementary schooling. With two dozen or so students, the school has a strong sense of family and community, McCliggot said.

This means new entrants settle in quickly—even those who are not familiar with dorms or life in rural areas. Due to its proximity to Tokyo, it’s not unusual for students to visit urban areas in the metropolis.

“We’re in Matsugo, Tokurozawa, a little patch of rural Saitama, but we’re surrounded by major urban centres. Shinjuku, for example, is just 45 minutes away.

“Last weekend, our dorm supervisor took some of our students to Fujikyu amusement park in Yamanashi Prefecture”.

Anglican down under

While JINIS and CIS are spreading their footprint in Japan, schools with a similar profile are doing the same around the region—including in Australia, Malaysia and New Zealand.

Cranbrook School, for instance, is an Anglican independent day and boarding school for boys based in Sydney, Australia. The school caters to students from pre-school to year 12 and offers the International Baccalaureate (IB) qualification.

Established 101 years ago, Cranbrook has offered “a rich and distinctive education to generations of young men, providing students with a truly world-class education,” said Headmaster Nicholas Sampson.

Students are supported to develop an international outlook at Cranbrook in many ways, including immersion “in different languages and cultures through student exchange programmes”.

To this end, “Cranbrook has enjoyed an association with the Nagoya-based Nanzan School, with students from both having taken part in an annual student and staff exchange programme for the past 17 years,” Sampson added.

The school’s Director of Admission and External Relations, Meredith Stone, said, “While Cranbrook has traditionally only seen a modest intake of students from Japan, interest from families based in the country has been steadily growing in recent years”.

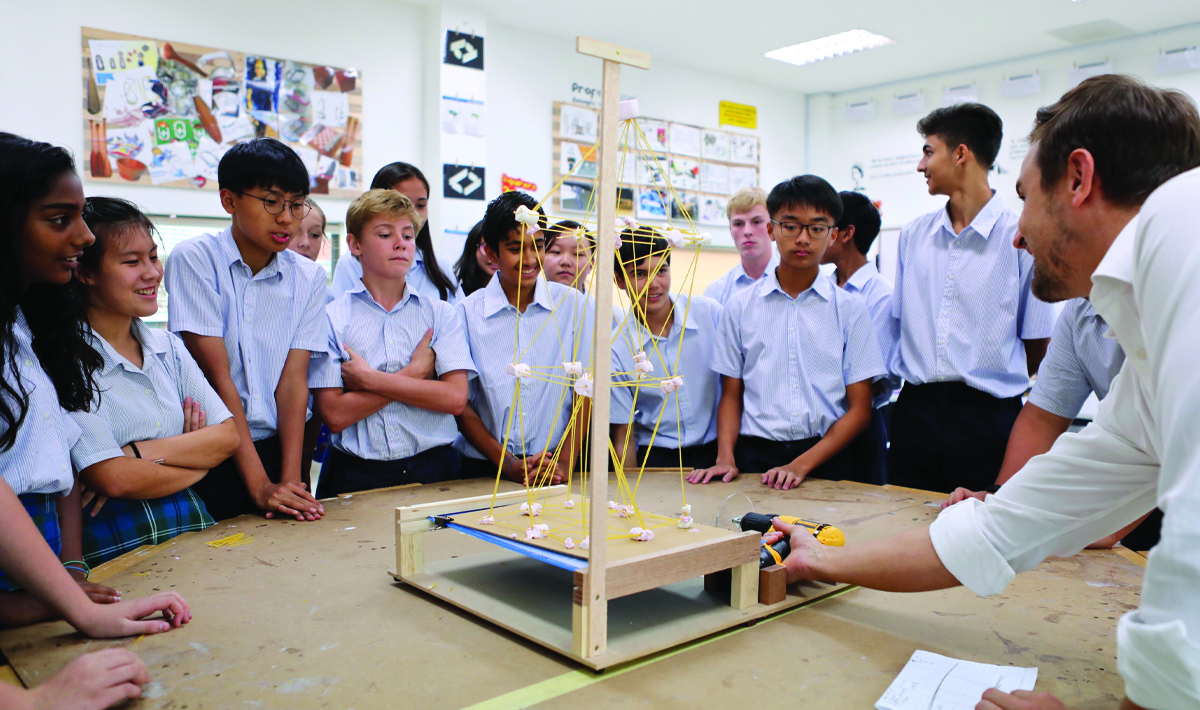

Students at Marlborough College Malaysia

Marlborough in Malaysia

As in Australia, international schools in Malaysia have, for years, offered European- or British-style boarding school options for aspirational parents in the region.

Adam Stevens

“Here at Marlborough College Malaysia, our philosophy is based closely on our sister school, Marlborough College, in the UK,” Adam Stevens, the school’s master told ACUMEN.

“In addition to the highest standards of conduct and achievement, we have a genuinely global outlook, welcoming children from over 40 nations and equipping them to attend many of the world’s most competitive universities”.

The academic and soft skills that Marlborough College Malaysia teaches—including music, drama and debating—are “further enhanced by the option to experience boarding”.

“Living together as a caring community promotes lifelong friendships and high standards. It sharpens children’s abilities to communicate and empathise,” he added.

This leads to the question: Have Japanese students boarded at the school? And, if so, how have they fared?

“We are pleased to have approximately 50 Japanese children aged three to 18,” Stevens said. “The intrinsic Japanese values of harmony, self-improvement and respect are a close match for those of Marlborough and its traditionally undemonstrative, understated British culture of honesty, courage, ambition and teamwork”, he added, saying that the experience of Japanese enrolees has been positive.

Marlborough College Malaysia welcomes students from more than 40 countries.

Passport to the UK

As Stevens and others noted, UK–Japan educational exchange and interaction—whether one is speaking about Japan, the region or Britain—is increasing across all levels of learning.

In many cases, parents based in Japan have looked to EF Academy, an international boarding school with campuses in New York and Pasadena, California, in the United States, as well as Oxford.

EF Academy has students from more than 75 countries. Five from Japan are based in Oxford, said Maiko Ozaki, the school’s head of admissions for Japan.

In the UK, where the school has had a presence since 2006, students enrol from year 10 (age 14) up to when they sit for A Levels or IB.

Ozaki explained that there are three main reasons why Japanese students choose to attend the school:

Many have a goal to attend leading universities in the UK.

Some have had difficulty fitting into the domestic school environment—where free expression of opinions, for instance, is uncommon. They see study abroad as a viable alternative. A number of experts made this point.

Others wish to improve their English language capacity, not to mention that they can choose, at A Level, a subject of their interest—something that is less likely to occur under the domestic curriculum in Japan.

Tokyo to Oxford

Ozaki may have a point. When parents and students in Japan choose an international school education, they often do so not simply to gain English skills or broaden horizons, but also with the goal of attending elite universities in Europe and North America.

Alison Beale

“For students who wish to study at the undergraduate level at Oxford, you need to have either A Levels, IB or one of the other qualifying examinations. The Japanese high school leaving exam is not one of them,” said Alison Beale, director of the University of Oxford Japan Office.

“So, most of our students at the undergraduate level who are Japanese come from either an international school or may be from a boarding school in the UK”.

For Beale, who sits on the Executive Committee of the British Chamber of Commerce in Japan, the ever-expanding landscape of international schools bodes well for Japan-originated students wishing to attend colleges such as Oxford.

“What I’m excited about regarding the rise of British- and international-style boarding schools is that, to get into universities in the UK, there are things that Japanese students find to be a big hurdle.

“One is English language. I think these schools will help because students get taken in from an early age and immersed in the language, so it will not be a problem for them”. All the experts interviewed more or less shared the same sentiment.

Miho Namatame graduated from

Miho Namatame graduated from