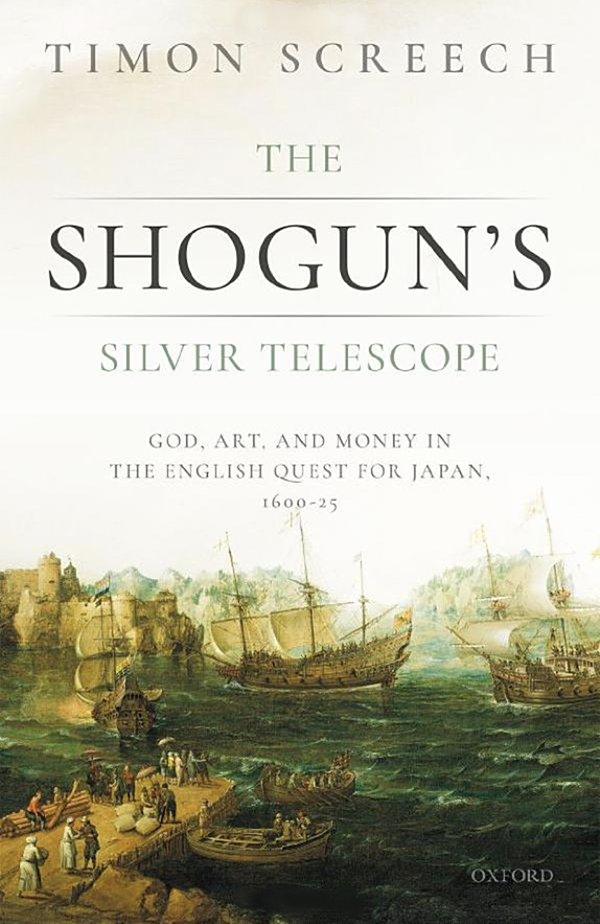

The Shogun’s Silver Telescope by Timon Screech (right), professor of the history of art at SOAS University of London, is a rip-roaring, fact-packed ride back in time to the world of Tokugawa Ieyasu and King James I—an era when the globe was shrinking at a sails’ pace.

The Shogun’s Silver Telescope by Timon Screech (right), professor of the history of art at SOAS University of London, is a rip-roaring, fact-packed ride back in time to the world of Tokugawa Ieyasu and King James I—an era when the globe was shrinking at a sails’ pace.

To counter relative commercial and religious isolation from much of the European continent, protestant England had long sought out new trading partners. Screech holds that Japan, a country of legendary riches (that most Japanese people today would have had trouble recognising), was the ultimate prize. Achieving the island of Cathay would open a river of silver to rival England’s Catholic enemies’ fast-flowing New World plunder.

Japan, for its part, coming to the end of more than a century of internecine warfare, was determined to impose a peace to end all peaces to build a stable and prosperous future.

Japan, for its part, coming to the end of more than a century of internecine warfare, was determined to impose a peace to end all peaces to build a stable and prosperous future.

The new shogun, Tokugawa Ieyasu, a visionary whose life work had been that final peace, was becoming increasingly disturbed by Catholic missionary shenanigans and the potential for a fifth column of subjects loyal to an outside power (i.e., King Philip of Spain and Portugal—coincidentally also England’s greatest foe). Ieyasu had furthermore come to trust an English castaway by the name of William Adams (page 31) whom he appointed a minor nobleman, and whose council he sought on maritime and ballistic matters. After nine years of no contact with his home country, Adams managed to get a letter out on a Dutch ship.

When the English realised that they had a man at court, and any trade deal should only be a minor formality, the newly formed East India Company redoubled its navigational efforts. Eventually, in 1613, Clove under the command of John Saris hove to in the lee of a mountainous bay on the western Japanese island of Hirado.

Screech’s story builds up to this moment, for Saris carried rich gifts as well as a letter of greeting from King James. Prime among the tribute was a silver-gilt telescope—cutting-edge technology only patented in 1608—the first to ever leave Europe and the first to be presented to a ruler as a gift. Ieyasu was delighted and arranged for the English to be granted extensive trading rights. A trading house, or factory, was promptly established in Hirado, with a network of sub-factories in major cities—a privilege that no other European nation enjoyed.

The English chief factor, Richard Cocks, who had an extensive anti-Catholic intelligence background, then set about ensuring that Ieyasu and his son, Hidetada, were fully aware of England’s prohibition of the Jesuits and the missionaries’ predilection for regicide (killing a monarch). Screech shows how the day after he heard this information, a deeply disturbed Shogun expelled all missionaries and forbade propagation of the Christian faith. History changed forever and, arguably, the events echo even today.

Screech’s solid scholarship and light writing style introduces this world in great detail, but, unlike many academic books, keeps the narrative going at the pace of a novel. He somehow manages to weave in stories as varied as England’s first shopping emporia, erotica, the genealogies of the great and good of both Japan and England, Indian art and the abductions and acculturising of unsuspecting Africans with espionage, conflict and adventure on the high seas. This is a highly recommended read for anyone with any interest whatsoever in Japanese or English history.