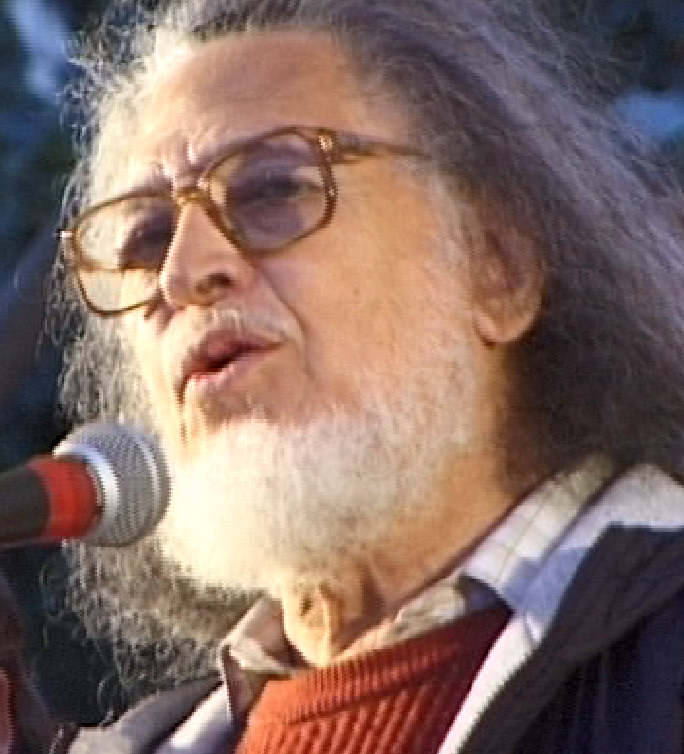

Dennis and Greg Brutus: living the legacy

With the Knights in White Lycra’s (KIWL) annual fundraising ride postponed until October, due to the coronavirus, I was looking for an interesting angle for this instalment in our regular series on the bike-riders. I didn’t have to look far. The diverse and determined do-gooders at KIWL are fertile ground for jolly eccentrics and eager raconteurs, but this time they outdid themselves by recruiting a scion of someone with serious struggle credentials and stories to tell.

KIWL founder Rob Williams and I both lived in South Africa a number of years ago, so we were honoured and fascinated when self-effacing Greg Brutus joined KIWL and I convinced him to talk about his rather famous father.

Please tell us about your dad, Dennis Brutus, the late poet and activist who was shot by South Africa’s apartheid police, hidden by your family and served prison time in a cell next to the great Nelson Mandela.

My father, Dennis, a high school English teacher, was smart, organised and energetic. His passion for fair play and equal opportunity put him on a collision course with the white minority government, arranging soccer, softball, cricket and other sporting contests between different racial groups. Seeing that only white athletes were allowed to represent the country, he wrote to international authorities to ask for equal access, or the expulsion of the whites-only teams. The crowning success of isolation came in 1971 with the expulsion of South Africa from the Olympics by the International Olympic Committee, and Dennis became public enemy number one. International cricket and rugby bans followed soon after.

Before leaving with the family into exile in England in 1966, Dennis was sentenced to 18 months in prison for his courageous battling. Most of his sentence was served in the infamous maximum-security prison on Robben Island, alongside many other liberation fighters: Govan Mbeki, Walter Sisulu, Indrus Naidoo, Neville Alexander, Nelson Mandela and countless others.

Before leaving with the family into exile in England in 1966, Dennis was sentenced to 18 months in prison for his courageous battling. Most of his sentence was served in the infamous maximum-security prison on Robben Island, alongside many other liberation fighters: Govan Mbeki, Walter Sisulu, Indrus Naidoo, Neville Alexander, Nelson Mandela and countless others.

In Mandela’s novel Long Walk to Freedom, he mentions your Dad’s arrival in prison. What was your favourite Mandela anecdote?

Probably my favourite Mandela-related anecdote can be found in the video clip “Nelson Mandela: Dennis Brutus helps hide Mandela” (youtu.be/bToRXOZmHns), in which my father talks about harbouring the fugitive Mandela at our home in Port Elizabeth. Naturally, he couldn’t go out, so instead he passed the time teaching my elder brothers how to box. As you probably know, he was quite an accomplished boxer in his early years.

Sanctions are always a tricky subject in business and politics, and I understand Dennis had strong feelings about this.

The United States has, for a long time, imposed economic sanctions against Cuba, Russia and North Korea—with few or, at best, mixed results. Sanctions against South Africa came in three waves and were effective because the pariah state had few friends: Israel, Taiwan and Iran.

The “No Arms for Apartheid” movement started in 1963 because military weapons were used against an impoverished civilian uprising for civil rights. Dennis was much more involved with the disinvestment of university and trade union investment funds, pulling out their significant holdings in firms and corporations that did business with South Africa. This grew across campuses, involving student strikes, teach-ins and occupation of key administration buildings. There are repercussions to this day, with shareholders seeking “ethical investment” that shuns profits made from the exploitation of people and the environment.

Dennis was particularly active in the “Cultural Boycott,” where celebrities, high profile artists, musicians and athletes, such as Arthur Ashe, cancelled tours of the racist republic. British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and President Ronald Reagan famously said that black South Africans would suffer most from sanctions, but Dennis and others, notably Archbishop Desmond Tutu, refuted those arguments. Sanctions worked because of twin pressures: internal resistance and international condemnation.

Nelson Mandela with May Brutus, Greg’s late mother

Dennis lived in exile in the United States in the 1970s and 1980s, but you ended up in Britain and Hong Kong. How did that happen?

I’m the seventh of eight children (four boys and four girls). Initially, we all moved to the UK as exiles in 1966. In the 1970s, my father got a job teaching at Northwestern University near Chicago, Illinois, so the family moved to the United States. But after two years, my mother returned to the UK and brought four of us younger children back with her. The rest remained behind with my dad.

I completed my studies in the UK, and my first job in 1986 was for a Japanese company, Komatsu, in the north-east of England. I like to think of my being in Japan now as a sort of “full-circle” story; I started out with a Japanese company and here I am more than 30 years later—in the twilight of my career—working in Japan.

In the intervening years, I had an incredible time backpacking around Southeast Asia with some friends, in 1992, and fell in love with Asia. I ended up settling in Hong Kong, where I met my wife and raised our two sons for the past 28 years. I spent much of my career working for AT&T as the head of corporate communications in the Asia–Pacific region.

After apartheid ended, Dennis became more involved in environmental issues. Please share with us his fight against the oil industry and global corporations.

After apartheid ended, Dennis became more involved in environmental issues. Please share with us his fight against the oil industry and global corporations.

Being an activist for social justice, Dennis observed that the same industrial giants exploiting people were also polluting the environment. Human rights could never be enjoyed in a choking, smoking, tarnished world where rivers turn into sewers of waste. Dennis joined many climate protests, for example at the Rio+10 Conference, in 2002, when the United Nations held its sustainable development summit in the Brazilian city to measure progress on Agenda 21 and the Kyoto Protocol. The street clashes were documented by filmmaker Riyadh Desai, and even featured in The New York Times!

Near the end of his life, Dennis was honoured with the Pete Seeger Peace Award for his environmental activism, and he received the award from his sick bed, adding a performance of his poetry, which can be found on the UKZN Centre for Civil Society website: ccs.ukzn.ac.za

Finally, how has his legacy affected you?

In two ways. First, I’ve been a passionate sportsman my whole life, and I’m delighted that my sons have also followed suit, both studying sport science and coaching at university in the UK. They continue to keep active. I took part in several team sports when I was younger, and now that I’m on the back nine, so to speak, I just try to keep fit and active with regular runs, bike rides, tennis and swimming.

Second, I’ve tried to help those less able to help themselves—especially in the area of education. I’ve been on the board of a charity called the Christina Noble Children’s Foundation (www.cncf.org) for more than a decade, supporting underprivileged and at-risk children in Vietnam and Mongolia. And now that I’m in Japan, I’m delighted to be supporting YouMeWe through the Knights in White Lycra. I’m really excited about the 500km charity ride that’s been rescheduled for October, due to the coronavirus. The ride will allow me to combine two of my passions—sport and fundraising—to help the underprivileged.