How Japanese soldiers helped the British in 1944 Java conflict

A new book by a World War II veteran has shed light on a little-known postscript to the conflict in the Far East—and one that was officially denied by the UK government of the day.

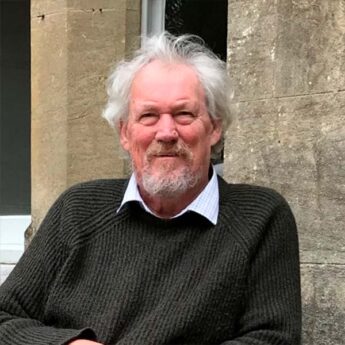

Released last June, Parachute Doctor: The Memoirs of Captain David Tibbs, MC, RAMC features photographs taken by the author. The first chapters cover his early years: growing up close to the Croydon aerodrome in south London; studying medicine at Guy’s Hospital, London; and joining the Royal Army Medical Corps as a 23-year-old doctor.

He then volunteered for parachute duty and was assigned to the 5th Parachute Brigade of the 6th Airborne Division.

Captain Tibbs was parachuted into the French region of Normandy on D-Day, 6 June 1944, and earned a Military Cross (MC) for his “untiring and devoted services to the wounded”.

He tended to those of the parachute regiment who were injured as a result of the break out from the Normandy beachhead, and was shot in the shoulder by a German sniper. He recovered and took part in repulsing the German offensive in the Battle of the Bulge, and in assisting both the massive airborne drop across the Rhine and the advance to the Baltic Sea to help prevent the Russians from moving into Denmark.

When the war in Europe was over, Captain Tibbs and his unit were ordered to the Far East, and were scheduled to take part in the parachute drop to recover Singapore from the Japanese garrison.

The plan was cancelled—to the troops’ “great relief”—after the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the Japanese surrender.

However, Captain Tibbs’ service was far from over. An armed insurrection had broken out on the island of Java, in what had been the Netherlands East Indies prior to Japanese occupation of the colonial state.

“The Japanese had occupied Java in a relatively peaceful fashion—very different from Burma and Malaya, where a violent and brutal assault was employed”, Captain Tibbs told BCCJ ACUMEN from his Oxford home. “They treated the Dutch colonialists in a comparatively benign way because the Netherlands, occupied by Germany, could offer no military opposition.

“The 5th Parachute Brigade went to [the north coast city of] Semarang, where the Dutch people said they had not suffered undue hardship.

“The Javanese, however, had a strong armed force under Sukarno, which opposed the Japanese in any way it could, so an active Japanese military force was necessary against them”, he said.

“When the Japanese war ended and the emperor ordered the Japanese to cease fighting, the Javanese insurgents turned their attacks towards preventing the return of the Dutch colonial power and commenced slaughtering Dutch people throughout Java”.

Two British officers who had recently arrived on the island were killed in the early stages of the fighting.

The Japanese forces took back military control and restored a degree of law and order until the British arrived, after realising that Dutch civilians were about to be massacred by the insurgents.

“This required some fierce fighting and caused a number of Japanese casualties, but they undoubtedly saved the lives of thousands of Dutch people”, said Captain Tibbs, now 92, and whose older brother, Lieutenant Ian Tibbs, had earned an MC for fighting the Japanese in Burma.

Captain Tibbs’ unit arrived in Semarang and immediately realised that they were not strong enough to repel the insurgents. As a result, the Japanese were brought under British command and ordered to defend a large sector of the city.

“This worked out remarkably well”, said Captain Tibbs. “The Japanese were fully armed with their own weapons, and were given extra help by artillery when needed.

“A peaceful and happy city was soon restored within a sizeable perimeter, and the Javanese insurgents were not able to cause much harm within this area”.

In contrast to the experiences of civilians in many other areas that the Imperial Japanese Army had occupied during the conflict, the Dutch who had lived through the years of Japanese control “were full of praise” for their former overseers.

“The Dutch begged us to treat the Japanese well and there was no difficulty in our doing this because the war with Japan was over and, in a way, the Japanese soldiers [in Java] were under our care and protection from the Javanese insurgents”, said Captain Tibbs.

“Moreover, there were no stories of bad behaviour by the Japanese [there] before this”, he said. “This group of soldiers was very different from the Japanese army in Burma and Malaya and, indeed, widely across the many Pacific islands”.

The attitude throughout the action was one of mutual respect and, at times, almost friendship between the two nations’ soldiers and officers, said Captain Tibbs. “They always behaved with impeccable military correctness”, he added.

“Inevitably the Japanese being, in essence, defeated troops, cannot have been delighted by our presence but never showed any hostility towards us”.

The same could not have been said about British public opinion towards the Japanese. As news filtered home about the way in which Allied prisoners of war had been treated, political expediency required the government to deny in Parliament that British troops were fighting alongside Japanese soldiers.

Captain Tibbs said the UK government’s denial was “perhaps understandable, with Japanese atrocities still so fresh in the mind”.

However, he has no ill-feelings towards those he encountered in Semarang and prefers to remember the positives of what they were able to achieve together.

As an honour and in recognition of their conduct, the Japanese were allowed to return home with their swords. Major Kido, the Japanese senior officer, presented his sword to Brigadier Darling, the British commanding officer, as a token of respect.

Captain Tibbs went on to develop a distinguished career as a surgeon.

Sabrestorm Publishing

£9.99