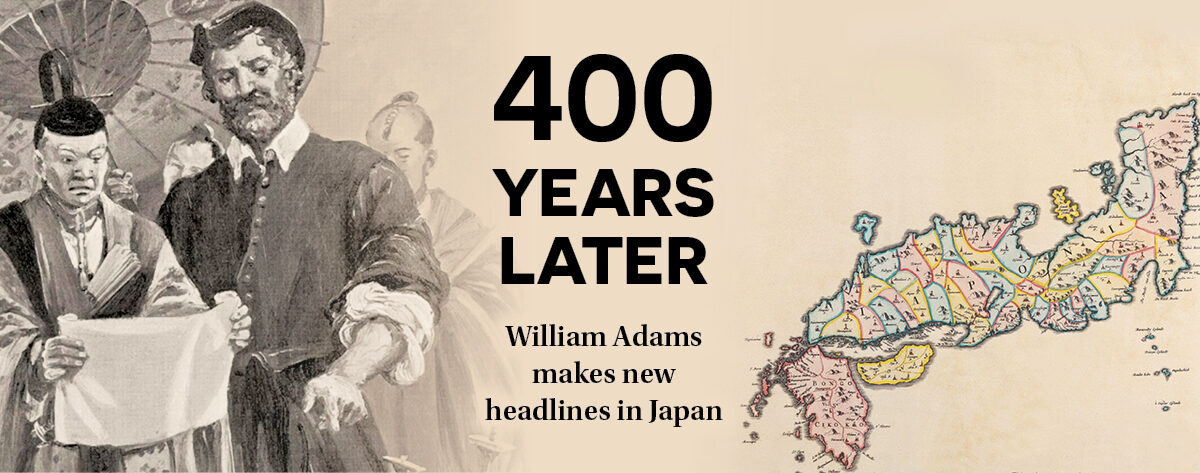

In April 1600, a Dutch ship, De Liefde, appeared off the coast of Kyushu. The pilot, William Adams (1564–1620), became the first Englishman to set foot in Japan. Until this time, Jesuit missionaries had asserted the religious and political unity of Europe. Adams’ presence proved this a lie, so he was summoned to Osaka Castle for lengthy interrogation by the most powerful lord in the land, Tokugawa Ieyasu.

Ieyasu, who became the Shogun, or hereditary military dictator, shortly after, used Adams extensively, granting him rank, a fief, and a wife—honours unprecedented for a foreigner. As his command of the language improved, the polyglot Englishman came to act as an interpreter and counsel on overseas affairs.

His life is well documented, but recently four new letters were discovered relating to his relationship with the Dutch East India Company, Ieyasu, his son Hidetada (who was to be the next Shogun), and Spain. The missives made national news in Japan, where Adams is still remembered and revered.

Below are translated extracts from a recent article published by the national daily Sankei Shimbun.

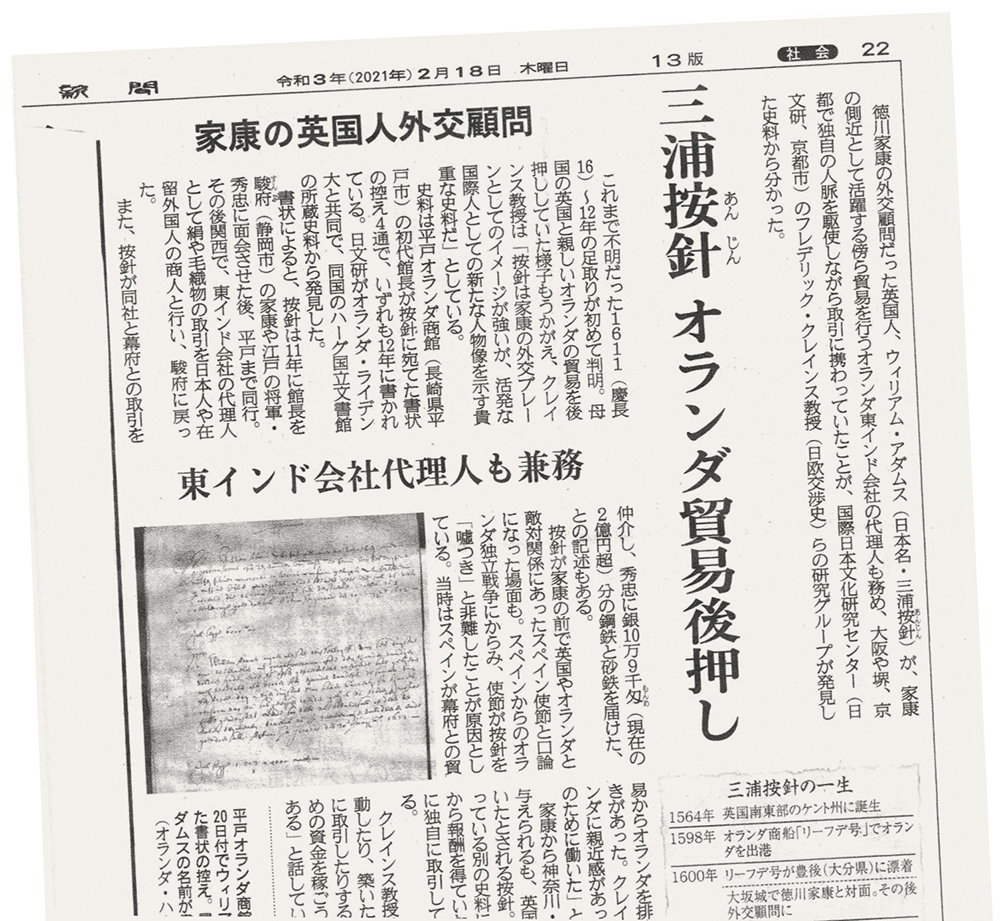

Ieyasu’s British Diplomatic Adviser

Sankei Shimbun 18 February

“Four letters have been discovered by Professor Frederick Cryns of the International Research Center for Japanese Studies, Kyoto, and members of his team, working in collaboration with scholars from the University of Leyden. The letters clarify a largely unknown part of Adams’ life, during 1611 and 1612.

“The letters reveal that Adams accompanied the chief Dutch merchant to meet Ieyasu at Sunpu (now Shizuoka City), and also to meet the Shogun, Hidetada, at Edo (now Tokyo), before taking him on to Hirado [now in Nagasaki Prefecture and where the Dutch trading post was located]. Adams then undertook work as a company agent for silk and woollen cloth in the Kamigata (now Kansai) region, before returning to Sunpu.

“The relations that England and the Dutch Republic had with Spain were tense, and the letters say that in Ieyasu’s presence, Adams argued acrimoniously with the Spanish ambassador after having been accused of lying about the Dutch struggle for independence fromSpain. At the time, the Spanish were trying to have the shogunate ban the Dutch from trade. In the view of Professor Cryns, “Adams was favourably disposed toward the Dutch and worked to promote their commerce with Japan”.

“The relations that England and the Dutch Republic had with Spain were tense, and the letters say that in Ieyasu’s presence, Adams argued acrimoniously with the Spanish ambassador after having been accused of lying about the Dutch struggle for independence fromSpain. At the time, the Spanish were trying to have the shogunate ban the Dutch from trade. In the view of Professor Cryns, “Adams was favourably disposed toward the Dutch and worked to promote their commerce with Japan”.

Dutch presence

The letters show just how involved Adams was in facilitating Dutch trade, and also how much he was favoured by Ieyasu, who seemed to have ignored the argument with a foreign ambassador in his presence—a normally unforgiveable breach of etiquette.

The legacy of Adams’ actions, as detailed in these letters, stretches down through the centuries. The Dutch East India Company factors were eventually the only Europeans permitted to reside in Japan throughout the years during which maritime restrictions were imposed on trade—the sakoku period—which ran from 1633 until 1868. The Dutch presence fostered extensive mutual transfers of technology, culture and general knowledge, with ramifications that have lasted until this very day.

In 1641, the Dutch East India Company was compulsorily relocated from Hirado to the manmade island of Dejima, in Nagasaki Bay, and there it remained for more than 200 years.

It is important that Adams arrived in Japan aboard a Dutch ship, and spoke Dutch, too. Soon, he also learnt to speak Japanese. It is not surprising, therefore, that he was enthusiastically employed by the Dutch as a polyglot business consultant.

English arrival

When the English arrived in 1613 and established the East India Company trading post at Hirado, they naturally turned to Adams for informed guidance. But Adams died in 1620 at Hirado. Inexplicably, after having operated for 10 years, the business was closed down in 1623, with the clear plan of returning later when better trading conditions prevailed.

However, when the firm attempted this, the sakoku period was well underway, and the original trading privileges were not restored by the Shogunate. Had the influential and experienced Adams survived beyond his 56 years, he doubtless would have prevented this calamitous mistake. Indeed, it is reasonable to assume that the Dutch and English would have been treated equally, as had been the case in the past.

So, what happened clearly changed the course of history in Japan, leaving just the Dutch as the informational filter between Japan and Europe. Had it been otherwise, the evolving UK could have contributed different values and perspectives for more than 200 years.

Had Adams lived longer, Japan these days would surely be different, if not even better than now.