In the global race to attract students and create world-class higher educational institutions, Japan has made some real progress—but a great deal more could be done. On 12 May, the British Chamber of Commerce in Japan (BCCJ) welcomed a panel that brought together academia and government at an event entitled Internationalisation of Japanese Universities. During the 90-minute virtual session, the panel discussed policy, practice and performance to see what students, employers, universities and policymakers can do to further develop the educational experience. Alison Beale, director of the University of Oxford Japan Office and BCCJ vice president moderated the event. Here are the highlights:

Tohoku University

Professor Kazuko Suematsu, special advisor to the president and deputy director of the Global Learning Center at Tohoku University, began the discussion. In her role, she helps develop international curricula and foster inclusivity within the campus community.

“When I first came to the university, about 17 years ago, my impression was that the school was academically strong but very conservative and rigid”, she said.

Fast forward to today and Tohoku University, founded in 1907 and located in Sendai, Miyagi Prefecture, has placed first in the Times Higher Education Japan University Rankings in consecutive years (2020–21). Home to more than 14,000 international students, the school was also selected as one of the first three institutions to receive designated university status from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT). Suematsu explained that this allows them to go beyond the structure of a national university and become more internationally competitive.

It’s quite a transformation since her arrival almost two decades ago. How did that change happen?

“It’s governmental planning for sure. Through the Global 30 Project, we were able to develop many international undergraduate and graduate programmes”, she explained, referring to the MEXT initiative launched in 2009 that aims to promote internationalisation of the academic environment of Japanese universities and acceptance of international students.

“We established overseas offices to recruit talented international students, and we have dorms where we intentionally mix international and domestic students on campus”, she added. “And with selection to the Go Global Japan Human Resource Development Project we were able to triple the number of outgoing students”.

Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology

In contrast is the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology (OIST).

“Internationalism was part of the design in creating OIST”, explained Graduate School Vice Dean Misaki Takabayashi. “There was a decision made to create OIST on the concept of internationalisation. And because we did not go through the growing pains of becoming international, we are, in a way, an experiment of what it would look like if every university began as an international university”.

The OIST student body comprises 45 nationalities, and when faculty and staff are included the number of countries represented is more than 50.

OIST’s standard language of business is English, and courses are delivered in English.

“Eighty percent of our students come from outside Japan, so they are, by definition, international”, Takabayashi said. “But having come from another country doesn’t make you necessarily multiculturally aware, instantly. So, swimming in the soup of our global community at OIST for five years at least gives you that training on a daily basis”.

She explained that there are two types of students at OIST:

- Those from outside Japan who would like to work here

- Japanese students who see a stepping-stone to working abroad

For the former group, a challenge arises because many do not speak Japanese—or at least not business-level Japanese—when they graduate.

For the latter group, she sees cultural aspects that must be overcome. “If I were to choose one strength that they need to gain to become international global assets for human resources, it is a shift in how they view themselves, gaining the mindset of ‘I can do this’ instead of being timid and humble—just recognising their own strengths and their own talents and their own capacity”.

Hartley Library at the University of Southampton

University of Southampton

Back in England, the University of Southampton has undergone its own global transformation in recent decades. Professor Peter G R Smith, pro-vice chancellor for international projects, explained that a push in the 1990s to internationalise UK higher education benefitted the school and today about 20% of the student body comes from abroad each year, representing more than 87 countries. And of the university’s £600mn annual turnover, some £100mn comes from international fees.

Business connections are especially important to the research-intensive school which hosts the UK’s National Oceanography Centre.

“If you look at the companies that work with universities, they tend to be the big multinationals. We’ve got very strong links with companies such as Rolls-Royce and Lloyd’s Register. Lloyd’s look after the insurance and certification of shipping. They’ve got a technical services centre within the university in Southampton and one in Singapore. So, we’re working with a lot of international organisations”.

Smith also mentioned an element not often considered by native English speakers.

“We conduct our education in English, because we’re in the UK, and I think that’s one of the big advantages that UK universities have. But there’s also a disadvantage, because most of our students don’t speak other languages. So, the incoming international students are very important to us in terms of internationalising our curriculum”.

Southampton is also building global connections through activities abroad, such as teaching collaborations with Nanyang Technology University in Singapore and an undergraduate curriculum with a focus on engineering which mirrors that offered in the UK taught on a 600-acre campus in Johor, Malaysia.

Smith also sees internationalisation of universities as critically important to the collaboration required for research.

“A very large number of collaborative projects, often funding schemes, are collaborative, and many of my colleagues in areas around, for example, social science, work very much with developing parts of the world”, he explained. “And when you look at the way we do scholarship, then everything’s international. International conferences are very highly regarded—we would normally be travelling to those—and if I think just about my corridor, I’ve got Greeks, Russians, Indians, Italians, I mean it’s just incredible. We’ve become very used to this very internationally diverse cohort of colleagues and students”.

i-graduate Asia

Joining from Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, was Guy Perring, regional director of i-graduate Asia, which proposed this BCCJ session. He talked about the group’s signature survey, the International Student Barometer. Established in 2005, this global benchmark for the international student experience is applied in more than 1,400 institutions globally and has garnered feedback from over 3mn students in 33 countries.

“Institutions such as Oxford and Cambridge use our data annually to get benchmark insights into what makes their students happy and satisfied, and how likely will they be to recommend an institution to their peers”, Perring explained. “We know that this positive word of mouth about an institution, and indeed a country, is actually vital in ensuring international students continue to come to your shores. I’m really passionate about the student voice and ensuring student views are included in government and international strategies and initiatives.

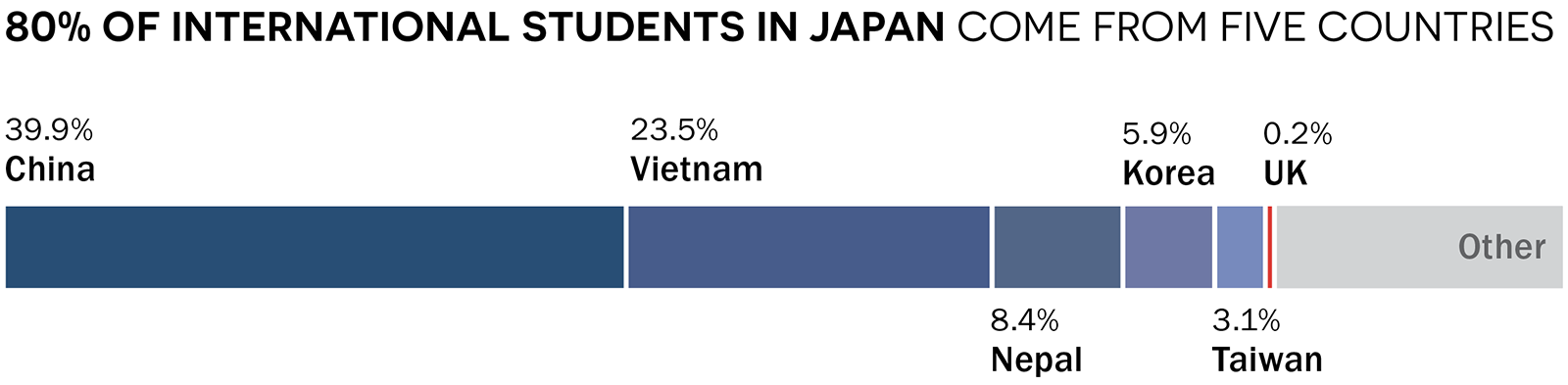

Source: Japan Student Services Organization (JASSO)

“I think all institutions need to understand why students make that very tough decision to study overseas, and also who influences that decision—be it parents, friends, teachers or a combination of them”, he continued. “I was looking at some of our global data this week in preparation for the webinar, and looking at the current international student makeup in Japan, 80% of your students are drawn from China, Vietnam, Nepal, South Korea and Taiwan. So, proximity plays a key role”.

- Perring said that i-graduate Asia’s global data shows that the key motivations to study overseas are:

- Impact of the qualification on a future career

- Reputation of the institution and the country’s educational system

- Personal safety and security

“I do think institutions across Japan, and indeed globally, need to build future employability into everything they do—and I would argue that it’s even more important now, given the current situation”.

Perring recommends:

- Career advice from academics who are actually teaching the students

- A careers office that caters to international as well as local students

- Relevant, up-to-date curricula for a future global career

- Building a range of internship opportunities for international students

“We also know from the data that the ability for students to work part time while studying, and having the opportunity to work post-graduation, is a key motivation for certain nationalities”, he added. “This is, to a large extent, dependent on government policy. But certainly, the UK has benefitted enormously from clear rules about post-graduation work opportunities and I’ve been urging governments across Asia who are looking to increase international student numbers to change some of their laws to allow this”.

Student perspective

After discussion of how universities approach international students and build communities, Elizabeth Gamarra, a PhD candidate at the International Christian University (ICU) in the west Tokyo city of Mitaka, shared her own experiences.

Born in Peru and raised in the United States, Gamarra had the opportunity to come to Japan through the Rotary International Peace Fellowship. ICU hosts the only peace centre for graduate studies in Asia. She now continues her studies in Japan as a MEXT fellow.

“For me, internationalism goes hand in hand with diversity, but it’s also the university’s willingness to hold this space for students”, Gamarra said. “Before coming to Japan, I thought it was homogeneous—and you could argue that it is in some ways—but after arriving in this particular space, you realise the diversity in Japan”.

She explained the many nationalities represented at ICU, as well as the many returnees—Japanese students who have lived abroad and have come back—and those who are half-Japanese. “I’ve been able to tap into groups that are very strong with the Hispanic and Latino communities, as well as the South Asian community, but also have that Japanese perspective to them. I feel very privileged to call them my friends and I think that embodies internationalism”.

MEXT steps

To share the Japanese government’s aspirations and strategies, Kuniaki Sato, director of the Office for International Planning at MEXT, joined the panel.

“We have been thinking in Japan that internationalisation is a very key and very important factor for our Japanese institutions of higher education, for our future”, he said. “As we all know, no country can live alone without linkage with international society. And talking about Japan itself, we are facing an ageing society. To maintain not only economic activities but also the activities in our society, we really need to be connected with international society”.

To promote internationalisation, higher education plays a very important role, he said, because not only do they deliver education, but they also conduct much of the country’s research. “For institutions of higher education, being more harmonised with international society and getting used to internationalisation itself is quite important”.

Sato explained the steps that MEXT has been taking to transform Japan’s system, starting with the Global 30 Project, which Tohoku University’s Suematsu mentioned.

“Global 30 focused on inbound—students coming to Japan—but it was only a five-year subsidy programme. Selected universities did a great job in terms of the acceptance of international students, but these efforts were limited”, he said. “Then we started our Top Global University Project. This is for 10 years, and we are now in the seventh year. We’ve been not only promoting the acceptance of international students, but actually changing the system internally so that universities get used to international ways”.

For the Top Global University Project, MEXT selected 37 universities which collectively account for 20% of university students and 20% of faculty members and staff in Japan. “This means we have a kind of critical mass”, Sato said, “so we really hope that these 37 select universities are going to play a very important role to lead the internationalisation of Japan’s higher education system”.

Kuniaki Sato

Kuniaki Sato

Director of the Office for International Planning

Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology

Misaki Takabayashi

Misaki Takabayashi

Vice dean of the Graduate School

Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology

Kazuko Suematsu

Kazuko Suematsu

Special advisor to the president

Tohoku University

Professor Peter G R Smith

Professor Peter G R Smith

Pro-vice chancellor for international projects

University of Southampton

Guy Perring

Guy Perring

Regional director

i-graduate Asia

Elizabeth Gamarra

Elizabeth Gamarra

PhD candidate

International Christian University

Alison Beale (Moderator)

Alison Beale (Moderator)

Director

University of Oxford Japan Office

BCCJ vice president