Reflecting on the dramatic changes in the global economy over recent years, Lord Patten, chancellor of the University of Oxford, recently gave a status report on the world’s major players and hinted at what might be expected from them in the future.

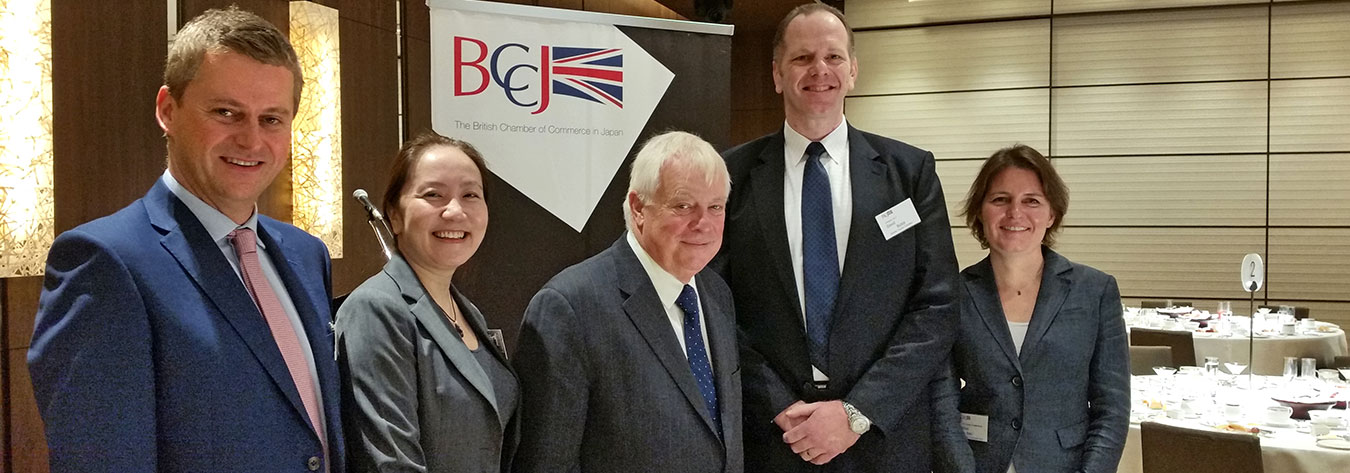

With insights gained from a long career in politics, including 13 years as an MP, as well as his position as last governor of Hong Kong and former chairman of the BBC, Patten was the guest speaker at the British Chamber of Commerce in Japan event, “Who will win in the 21st century?”, on 20 October.

“It’s very difficult to think of a single global problem that we could solve without either American leadership or at least without America making a major contribution”, he told the audience at the Grand Hyatt Tokyo. Yet, he said, “America is no longer able on its own to simply lay out terms for solving international problems”.

He pointed out some of that country’s characteristics: its defence expenditure is equal to that of the next 10 spenders combined; it is home to 42 of the world’s 50 best universities; and its approach to immigration is very open.

While over the next 30–40 years, the population of Europe is expected to fall 20%, the population of the US is expected to increase substantially. In fact, it is the only developed country that can expect to see this trend.

The US has “an extraordinary capacity for self-renewal and a terrible political system: increasingly excessively partisan, with more checks than balances”, he added.

Meanwhile, according to Patten, Europe requires reform for it to become competitive on the global stage, as it once was.

“In the 19th century, one of the reasons for Europe’s success was that our share of the world population went up from a fifth to a quarter. Europe was growing very rapidly—and exporting people—but above all, creating prosperity through that demographic”.

Not enough money is spent on research and development, he said, adding that Harvard University receives 80% of its research income from the government. This is double the percentage that the University of Oxford receives—a trend that can be seen across Europe.

Also with a key part to play globally are the countries that have turned into emerging markets and joined the world economy.

“When China or India, for example, start to play catch-up on the rest of the world, the consequences are, of course, extraordinary”, he said.

In 1965, the US was responsible for 37–38% of world income. Now, the total is 22%. This can be seen as an example of American decline. But it also shows that, while emerging markets are behind Europe, Japan and the US in terms of capital growth and capital income, they are making a big difference in aggregate on a world scale.

China’s economy has grown by more than 8% a year in all but eight of the past 35 years. By the 2040s, in terms of population, India’s is expected to be very young, economically active and the world’s largest, followed by that of China.

“China is moving from labour surplus to labour shortage more rapidly than any society in human history”, he said.

Yet, there are problems. These include air pollution, water shortages and concerns about the political system. Even the last Chinese prime minister, said Patten, declared that the Chinese model is unsustainable for demographic and environmental reasons.

“The secret of growth over the last century and a half or two centuries has been found in those countries that have managed to produce inclusive political systems, which have meant that you have them sustained by incomes of economic systems”, he said.

He added that the future lies with those who can manage the balance between inclusive political and inclusive economic systems, in the way the US, Japan and Europe have done.

Speaking of UK–Japan ties in the future, Patten said that “shared values will be a very important element in any political diplomatic relationship”.