How bilateral cooperation can bring stability

- Planning needed for a more efficient and secure world order

- Failing states pose a threat to regional and global stability

- Lessons in risk management can be learned from recent crises

Our world is becoming “ever more perilous”, and a great deal of responsibility rests on the shoulders of the UK and Japan, according to Sir John Major KG CH, former British prime minister.

Both countries need to ensure that global society is able to negotiate the challenges that we face now, and those that are to come in the future, he explained.

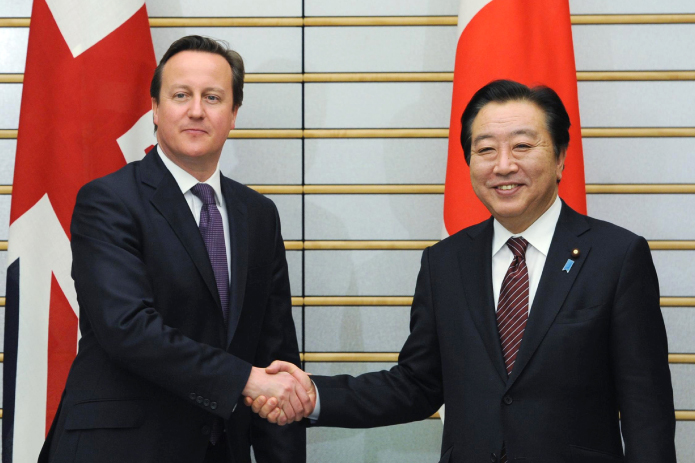

Major was speaking in early October at a two-day UK–Japan Global Seminar in Tokyo, held in partnership with Chatham House, the Royal Institute of International Affairs, the Great Britain Sasakawa Foundation, and the Nippon Foundation.

“One only has to think of the mayhem in Syria, Iraq and much of the Middle East, the fighting in Crimea, the military and political conflicts in Asia, and the democratic deficit in parts of Africa to see where problems lie”, he said.

“This list is far from inclusive”, he added. “A good dose of enduring optimism, and a firm belief in a more prosperous and secure world for all, are prerequisites for the world leaders of today as they confront the critical issues before them”.

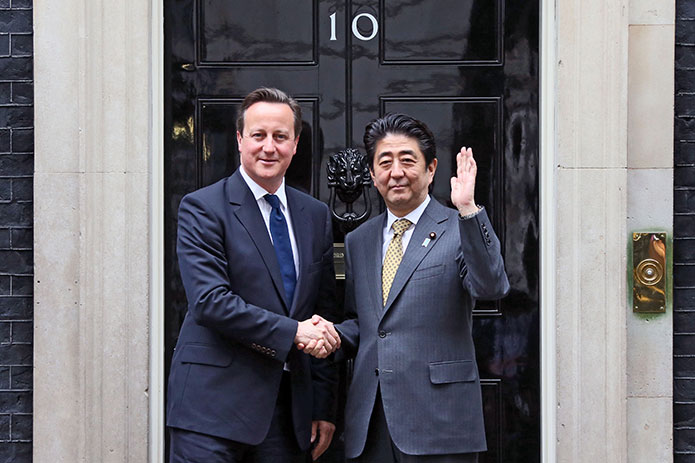

Major praised the leadership of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe for his commitment to the idea of Japan playing a more proactive role in international affairs, but pointed out that security tensions in Asia “must not be ignored”.

At the top of that list of concerns is China, he said.

“I have spoken often enough about welcoming China’s emergence as an economic power”, he said. “I do that most genuinely. Less welcome is that China is expanding her maritime presence in the East and South China Seas and, in so doing, is creating tensions with—among others—Japan, the Philippines and Vietnam.

“The reason for concern is clear: China is acting in a fashion that potentially challenges the international order which, if she miscalculates, may provoke a response”, he said. “This may never happen, but is a risk, nonetheless. To recognise that risk is the first step in reducing it”.

More concerns revolve around North Korea, including the country’s development of nuclear weapons, and popular nationalism that evolves into anti-foreigner sentiment.

The relative weakness of Asia’s institutions—demonstrated by the inability of the six-party talks in North Korea to find a solution to the country’s nuclear weapons programme—rivalries for access to natural resources and energy, as well as emerging separatist movements are also cause for concern.

“I passionately believe that, if we work and plan for a more efficient—and better—world order, we can build a more prosperous and secure future for all”, he said. “But we dare not be complacent about security in Asia.

“The seeds of conflict are there. The risks are real and not phantoms. They may come in many guises, and be related not only to new security challenges, but to governance in the economic, social and energy spheres.

“As we identify these threats, we must seek to head them off. And by ‘we’, I mean everyone who can contribute. I repeat: in our global world, Asian problems impact far beyond Asia, and we all have a stake in the solution”.

Following Major’s speech, delegates examined many of the issues that he had touched on in a series of focused sessions.

The question of failing states was addressed in a discussion chaired by Robin Niblett, director of Chatham House. The conversation considered the threat failing states pose to regional and global security, and the ways in which the international community might respond to such threats.

Also considered was the track record of the UK and Japan in addressing such challenges, including in the Ukraine, the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan and the State of Libya.

The remaining two sessions of the first day looked at disaster management, including the lessons that can be learned from recent crises regarding risk reduction and preparation. There followed an airing of the issue of democracy in transition, and the importance of external intervention in shaping such transitions.

The final day of the conference homed in on the situations in the Syrian Arab Republic and the Republic of the Union of Myanmar, examining the issue of how Japan and the UK might help in both nations.

The remaining session was chaired by Sir David Warren KCMG, former British ambassador to Japan, and chairman of the Japan Society in London.

He asked why Japan has reversed its “zero nuclear” goals three years after the disaster at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant, whether public concerns can be allayed, and went on to explore broader security concerns over Japan’s plutonium stockpile.