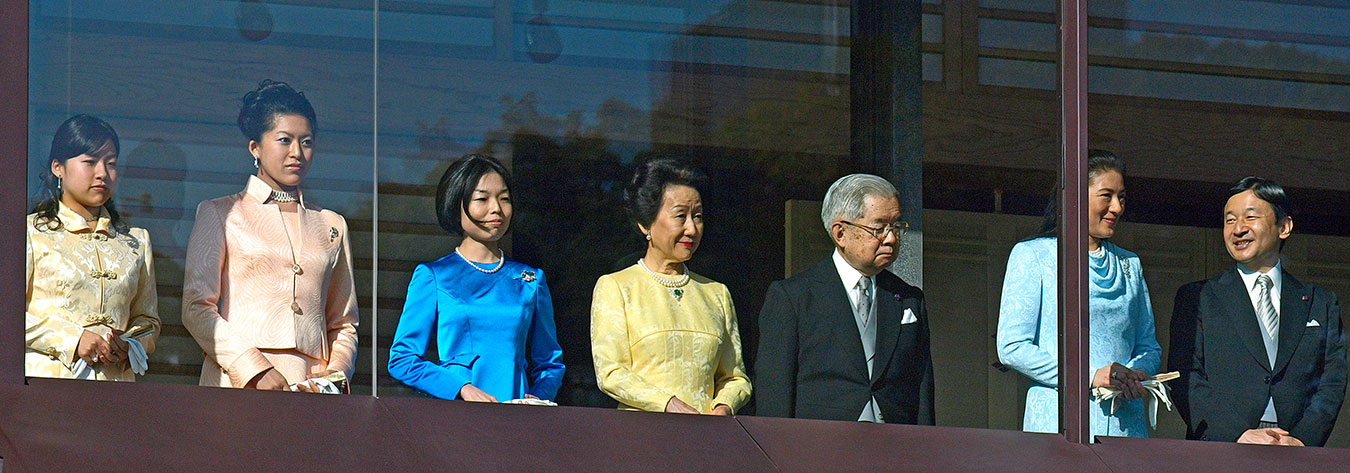

The recent death of Prince Mikasa leaves only four eligible heirs to the Chrysanthemum Throne: Crown Prince Naruhito, Prince Akishino, Prince Hisahito and Prince Hitachi. The Imperial Household Agency sees this as a major challenge and has quietly called on the government to debate ways to secure a stable succession.

This has opened up the old controversy of whether women should be allowed to ascend the throne. Currently, under the 1947 Imperial House Law only male members of the family line are eligible. However, a government panel established in September to study whether or not the present Emperor might abdicate has not been asked to debate this sensitive question. It is widely known that Prime Minister Shinzo Abe is not in favour of female succession, writing in 2012 in the Bungei Shunju that he was “clearly opposed” to having a female emperor.

Other administrations, other ideas. A decade or so ago, when Junichiro Koizumi was prime minister, there was a fierce debate on whether to revise the Imperial House Law. Koizumi gave up on submitting a bill to the Diet on the birth of Prince Akishino’s son, Prince Hisahito, in September 2006, but he still expressed concern that Imperial succession could become unsustainable.

By contrast, there are seventeen immediately eligible successors in the UK’s House of Windsor, and they include princesses as well as princes. And under current laws, the total number of heirs is estimated to be many more.

There are precedents for the throne being passed to a woman, although they are historic. During Japan’s recorded history, eight women have served as reigning empresses on 10 occasions. Two of them re-ascended the throne after abdication under different names. The first historically attested holder of the position was Empress Suiko, who reigned from 593 to 628, and the last was Empress Go-Sakuramachi, who abdicated in favour of her nephew in 1771.

Women were specifically barred from the throne for the first time in 1889 by a Prussian-influenced constitution adopted during the Meiji Restoration. The prohibition was continued by the Imperial House Act of 1947, which was enacted under Japan’s post-war constitution during the US occupation.

The 1947 law further restricts the succession to legitimate male descendants in the line of Emperor Taisho only, and excludes other male lines of the imperial dynasty, such as Fushimi, Higashikuni and so on. The law also specifically bars the emperor and other members of the imperial family from adopting children.

But in January 2005, the Japanese government announced that it would consider allowing the crown prince and princess to adopt a male child to avoid a possible crisis in the line of succession. In fact, adoption from other male line branches of the Imperial line is an age-old tradition for dynastic purposes, and was only prohibited in 1947 under Western influence. In October of the same year a government-appointed panel recommended an amendment to the imperial succession law.

However, in November 2005, it was reported that the emperor’s cousin, the late Prince Tomohito of Mikasa, had objected to the reversal of male-only succession and suggested permitting the emperor or crown prince to take a concubine, which had been permitted under the former law. The emperor has so far refrained from voicing his opinion on the issue, but has urged the government to consider the views of his two sons.

The Imperial Household Agency is known to harbour serious concerns over whether the imperial family can maintain its activities in a stable manner. In 2011, the grand steward of the agency told then-Prime Minister Yoshihiko Noda that it was a matter of urgency to enable female members of the imperial family to create family branches.

The debate has continued and will no doubt go on as the future of the current emperor increasingly becomes the focus of attention. But in 2012, a Kyodo News poll showed that 65.5% of Japanese people supported the idea of allowing female members of the imperial family to create their own branches of the family and to retain their imperial status after marriage.