How science helps create global leaders

The programme offers a chance to tackle real-life challenges.

The future looks bright according to organisers, participants and sponsors of the UK-Japan Young Scientist Workshop Programme. This year marks the 10th anniversary of the ground-breaking initiative, which involves high school students over the age of 16 living and working together to explore scientific fields.

The brainchild of the Clifton Scientific Trust, the programme aims to enliven young people’s experiences of science and its applications by providing them with a real-life challenge that gives their schoolwork meaning and context.

In small teams under the guidance of professional scientists and engineers, participants explore an issue through research and debate. At the end of the workshops they give public presentations to outline their achievements.

The yearly programme also hopes to combat the problem of an education system that leaves students uninspired by science, and unequipped with the questioning skills required in the 21st century, according to Dr Eric Albone MBE, director of the Clifton Scientific Trust.

“Students are capable of doing far more than is often imagined”, Albone told BCCJ ACUMEN. “Young people are excited about being in the driving seat of science, being given some responsibility to think for themselves, and to work across cultures. And our approach is attractive to girls as well as boys”.

Opening a special event to celebrate the programme’s 10 years of achievements at the British Embassy Tokyo on 11 August, Ambassador to Japan Tim Hitchens CMG LVO welcomed the work.

“We believe the programme to be an extremely worthwhile initiative to strengthen the cooperation and cultural understanding between our two countries and to spark young minds’ interest in science and engineering”.

Japan and the UK have a long history of educational and scientific collaboration, dating back to about 400 years ago, when the British King, James I, sent a telescope to the country as a gift.

Participants shared their experiences at an event at the British Embassy Tokyo.

Addressing needs

As the governments of both the UK and Japan currently share serious concerns about the number of young people pursuing science-related careers, programmes such as the Young Scientist Workshop are particularly valuable.

Speaking at the embassy event, Shinichi Yamanaka, administrative vice-minister of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), congratulated the programme in making science attractive to students.

In Japan, he explained, one problem is social pressure. Teachers and parents of young people who are good at science encourage them to pursue careers in medicine rather than other scientific disciplines.

MEXT is aiming to inspire more young people to consider a science-related career through its Super Science High Schools programme.

In cooperation with universities and research institutes, and with support from the Japan Science and Technology Agency, these special schools aim to improve the quality of science and mathematics education by providing enriched teaching methods and materials.

They also offer classroom teaching in English, which is designed to prepare students for international activities.

In the UK too, the government has been working to turn around the lack of interest in science among young people.

This month, successful British entrepreneurs will launch a national media campaign for Your Life, the government’s latest scheme to ensure the country has the maths and science skills to succeed in the global economy.

The programme, targeting 14- to 16-year olds, aims to boost participation, particularly among girls, in science, technology, engineering and maths at school and beyond. Over 180 organisations have pledged their support.

In light of this work, some say the UK-Japan Young Scientist Workshop Programme was ahead of the game when the seeds of the initiative were sown over a decade ago.

Building on workshops in Bristol in the late 1990s between the Clifton Scientific Trust and its Japanese colleagues that were designed to share best practice, the programme began in 2004.

To date, workshops have been held on a number of campuses in the UK and Japan, including at the University of Cambridge, Kyoto University and Kyoto University of Education. Since the Great East Japan Earthquake and tsunami, the programme has worked with schools in the disaster-struck region.

This year, in addition to a workshop at Cambridge on 20–26 July, Tohoku University for the first time played host, on 3–9 August. A total of 58 students, 32 of whom are female, attended the Cambridge workshop, with a similar number in Tohoku.

Deputy headmaster at Rikkyo School in England, Dr Toru Okano, who has been involved in the programme since its early days, said that working with scientists of the world’s leading universities is a dream come true for students.

One of this year’s workshop participants, Barney Lewis, said the programme had made him consider research as a career path.

“I was lucky enough to work on the atomic force microscope, which is really cutting-edge research lab stuff, and it has shown me how interesting and exciting science can be when you’re on the brink of finding something new”, he said.

Another success story is Mariko Takahara, a participant at the 2008 workshop at Surrey University who now is reading bio chemistry at Kyoto University.

“I can clearly remember those wonderful days. The programme was so exciting and it changed me a lot”, she said. “I thought how lucky I was to have a chance to study what we do not learn in a Japanese high school”.

As a registered charity, it is only with more funding that the trust can continue its work, explained Albone.

“Money is needed because we have none ourselves, but we want to have support of all sorts and encouragement of ideas”, he said.

Haruhiko Tsuyukubo of Rolls-Royce plc and Kentaro Kiso, of investment bank Barclays, two of the firms that sponsor the programme agree.

“We can still change the future by investing in young talent, Kiso said. “No matter how advanced our modern-day technology becomes, we know that nothing can beat face-to-face physical exchanges”.

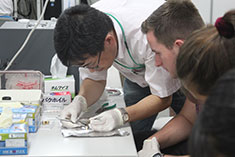

Professional scientists guide the young people in their research.

Cultural bridge

Champions of the programme are keen to point out that it is designed not only to make young people passionate about science, but also to help them see their own lives in a global perspective through cross-cultural communication.

It is this personal dimension for which students have been particularly vocal in expressing their appreciation.

“Each of us has our own background, and we worked on problems from every perspective, which stimulated my eagerness and broadened my view”, said Fukushima High School student Tetsuri Takami, a participant of one of this year’s workshops at Tohoku University.

“In order to solve various problems on a global scale, it seems indispensable to cross borders and to work together.”

Another participant, Matthew Lawson of Thomas Hardye Academy in Dorset, explained how the programme had influenced more than simply his views about science.

“We come to everything with a fixed perspective, but what I guess I learned from this experience is to throw that out of the window and just come in and really be open-minded”, he told BCCJ ACUMEN.

During the programme students live together, take part in social and cultural activities, and visit local sites of interest. This year young people from the schools of the Tohoku region took their British counterparts to visit places that are still recovering from the impact of the Great East Japan Earthquake and tsunami.

Speaking of the experience, Lawson said “What I found about Britain and Japan is a universal sense of empathy”.

Other UK participants explained that they were inspired by having witnessed, firsthand, both recovery efforts and the communal spirit that was making them successful. Japanese students, meanwhile, reported they were proud to have been able to convey the spirit of the region’s recovery, in doing so helping to restore Tohoku’s vibrant image.

Looking to the future

Given that in Japan, globalisation is being heralded as a means of improving the economy, Katsuji Jibiki, a spokesperson for workshop sponsor Mitsubishi Electric Corporation, believes the programme has a part to play.

“Internationalisation means to understand the cultural differences between one country and other countries, and to respect those cultural differences. So, this UK-Japan Young Scientist Workshop is the ideal programme to develop future leaders—not only in the science field but also in the global corporate field.”

Through the programme, participants reported that they were able to make friends, appreciate each other’s differences, and learn from each other.

“What surprised me most in working with [the British students] is that they always had their own opinions and expressed them clearly. They had confidence in themselves, and I thought I should be more confident and express my opinion”, said Takahara of her experience.

Fatima Taha, a 2014 participant from UCL Academy London, found much in common with her Japanese counterparts. “It seems that we, as students, all share the same goals—of personal development and of ways to improve society”, she said.

The programme was recognised in both the 2008 European Union Sixth Framework Programme “Form It”, and the subsequent report, as an excellent example of international collaboration to bridge the gap between research and science education.

Those who have witnessed the programme’s impact are confident it will leave a lasting impression on participants, long after they have returned home.

London’s Seven Kings High School biology teacher Lizzy Murdock, who accompanied the students, said the programme had developed their skills and confidence.

“As teachers, we have seen our students grow in a really short period of time”, she said. “I think it will be nice to see them go back to our schools and talk about [the programme] and inspire other students”.

With participants citing an interest in further study of the other country’s culture and language, as well as overseas in that country, the programme will no doubt also result in a further deepening of UK–Japan relations.