Personal search for a role

I have had the honour and pleasure of meeting Charles, The Prince of Wales, on a number of occasions in both the UK and in Japan. I find him an interesting and interested interlocutor.

I have had the honour and pleasure of meeting Charles, The Prince of Wales, on a number of occasions in both the UK and in Japan. I find him an interesting and interested interlocutor.

Though we obviously come from extremely different backgrounds, there is a sense in which I identify with him. We are the same age—he is just a week or so older than me—and, as a small child, I was dressed as closely as possible in likeness to the young prince, though my parents could never have afforded the designer styles of today sported by young Prince George. Post-war British austerity and rationing played their part, of course, but camelhair topcoats did feature.

As a boy, I read stories of the prince’s time at Gordonstoun, the somewhat spartan public school in Moray, Scotland, where cold baths and punishing routines were thought to build character. And I felt for him: how I would have hated it!

It turns out those were bleak years for the prince himself and yet he has built much of the Gordonstoun philosophy into the various schemes that make up the UK charity he founded: the Prince’s Trust. Notably, however, he has not subjected his sons to the same educational fate.

It is well known that the prince has struggled to find a role for himself as he waits to inherit the throne; that inheritance a poisoned chalice as it almost certainly means the demise of his mother, whom he loves and reveres. In the volume under review, the prince reveals that he is devastated at the thought of his parents’ passing, just as he grieved greatly the passing of his grandmother, the Queen Mother.

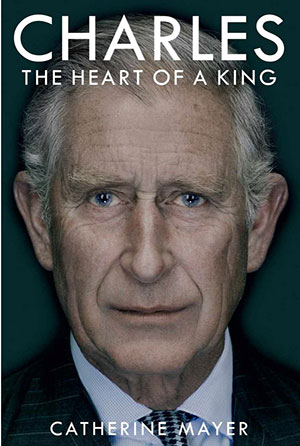

Catherine Mayer’s book explores this dilemma in sensitive and affecting detail. Throughout, she quotes the prince’s closest friends and his courtiers in telling his story. “The Firm”—a nickname by which the British Royal Family is collectively known—has been quick to point out that this is neither an official nor an authorised biography. Nevertheless, it has a ring of authenticity about it.

Mayer, who is editor at large for Time presents a balanced, well-written account of a life that has attracted most intense scrutiny. There is nothing “sensational” about the book; she does not attempt to shed new light on the Diana years, for example, but, equally, her approach is not in the least bit sycophantic. On the contrary, she is highly professional in her approach, her research is meticulous and she writes with a fluency that is easy to read.

As author of an earlier book on the prince, Born to Be King, it is hard to escape the thought that Mayer is somewhat fixated on him as a subject for exploration. While I have not read the earlier volume and cannot compare the two, just how much differentiation can there be?

That said, the prince is a complex man, and one who is much misunderstood. Books such as the one under review go a long way to help us understand the man who will be king.