Growing up in the UK in the 1950s I would, from time to time, come across the “made in Japan” label on, perhaps, a cheap tin automobile or a clockwork monkey—also tin. They were not expected, or indeed designed, to last. They were tawdry trinkets to be won at the coconut shy, destined to be relegated to the back of the toy box, and soon to be forgotten.

In those days, not many could have imagined that, in just a few decades, the words “made in Japan” would signify products that come from a country that prizes both exceptional craftsmanship and industrial perfection.

Naomi Pollock’s beautifully produced book showcases 100 new products, ranging from modest kitchen utensils to a futuristic-looking (though practical) Segway-like device aimed at wheelchair users, that demonstrate both these qualities.

Each item is impeccably photographed and accompanied by a one-page introduction to the designer (or design team) responsible for creating it. The text, crisp and to the point like the items it describes, is designed to do the job it sets out to do without superfluity.

Indeed, the book stands as an example of what is often best in Japanese design: simplicity. From the layout grid, to the endpapers and the meticulous binding, it exudes quality.

The volume is a delight to handle, a joy to dip into and—itself an objêt d’art—enhances the bookshelves. Appropriately, the foreword is written by Reiko Sudo of the NUNO shop in Roppongi’s AXIS design centre (where you’re likely to find at least some of the featured products). Like the author’s introduction that follows, it sets just the right tone for browsing the pages to come.

Shinto is the indigenous and older of Japan’s two main belief systems (the other being Buddhism, a 6th-century import). It rests on faith in kami (spirits)—although gods is the usual, though slightly misleading, translation—that are to be found in everything, from people and animals, to places and even inanimate objects such as rocks or trees.

Thus, it is a faith that is at the same time polytheistic, pantheistic and animistic, and something that is surely special. Shinto rites and practices are very much alive in today’s Japan, so much so that most Japanese take them for granted and many would be surprised if reminded that they were practising Shintoism.

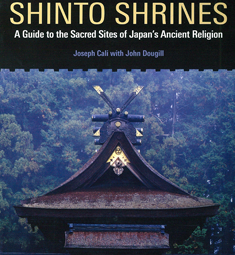

For the majority of non-Japanese, the most obvious encounter with Shinto is at the many shrines that are all around us (an estimated 80,000 nationwide). Cali and Dougill’s impressive book, presenting itself as a guide to just a select few of these, is far more than that.

The introduction is easily the clearest and most accessible explanation of Shinto that I have read. There is an immense amount of detail about the history of Shinto, the types of kami, and how this most Japanese of faiths interrelates with Buddhism, Confucianism and Christianity, among other belief systems.

There are numerous helpful illustrations, including ones of the most important features of a typical shrine, as well as of the clothing worn by priests and shrine attendants.

In addition, of great interest is the way that the authors pose the question: “What benefit might there be in visiting a shrine for someone who has grown up in another country with different cultural and religious values?” Their answers are compelling.

The authors’ enthusiasm is infectious and the depth of their knowledge, and obvious love and respect for the subject, is evident on every page. Thoroughly researched, well written and cleverly illustrated, the book should be a must-read for anyone wishing to delve into this most fascinating aspect of Japanese culture.