Shut In

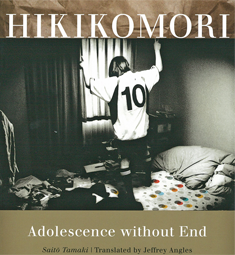

In 1998, a relatively unknown Japanese psychiatrist published a book about a phenomenon he had noticed among his patients, especially young males.

These people—known as hikikomori—withdrew from society, taking to their rooms for months or even years, and rejecting contact with the outside world.

Enabled by parents who indulged their isolation, the so-called hikikomori risked never being able to return to the workplace or to normal social interaction.

The book became an instant bestseller and propelled its author, Dr Tamaki Saito, into the limelight. Today he is one of the most high-profile commentators on Japanese youth and youth culture.

Now, thanks to the University of Minnesota Press, we have access in English to Dr Saito’s findings. The translation of the book by Jeffrey Angles (associate professor of modern Japanese literature and translation at Western Michigan University) is masterful.

Angles successfully echoes Saito’s voice and maintains the same accessible language that made the original publication such a huge success. Thus, even if one has no background in psychiatry or related studies, one is helped to understand the complexities of this condition.

Dr Saito did not coin the term hikikomori; it is acknowledged in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition—a diagnostic manual, published by the American Psychiatric Association, that is widely used around the world.

However, in the manual the condition is considered a symptom, while Dr Saito argued that it ought to be recognised as a diagnostic category in its own right.

While some have argued that withdrawal is a symptom of depression, Saito points out that not all depressives withdraw from society to the same extreme degree.

Nor do all those that withdraw display the classic signs of depression; within their own world some appear to be content with their choices.

Dr Saito estimates that something in excess of 1mn people are afflicted, although he acknowledges it is very difficult to establish an accurate figure. Individuals suffering from the disorder are reluctant to reach out for help, while their parents and siblings are often too embarrassed to seek assistance.

Shut Out

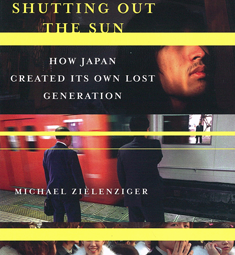

A completely different interpretation of Japan’s hikikomori shut-ins comes from Michael Zielenziger, an American journalist who spent seven years living in Japan.

Zielenziger is now a visiting scholar at the Institute of International Studies at the University of Berkley in California.

He seems to suggest in his book that the cause of the condition lies in the pathological nature of Japanese society, rather than that it is a personality issue (a notion from which Saito in Adolescence without End deliberately distances himself).

Shutting out the Sun, a product of keen research, is most readable. The book includes some engaging interviews with people whom it must have been difficult to persuade to talk with the author.

Unfortunately, his argument is weakened by the fact that he uses his own cultural values as a measure of what he perceives to be right.

Zielenziger extends his thinking on the subject to South Korea. Although this is an interesting twist, even here his arguments lack the discipline that is needed to make the case in either psychiatric or anthropological terms.

The book would be far more accessible and the arguments more convincing if the author had remained focused on the phenomenon as it affects Japan.

Nevertheless it is a worthwhile undertaking that deserves the attention it has enjoyed in the mainstream media.