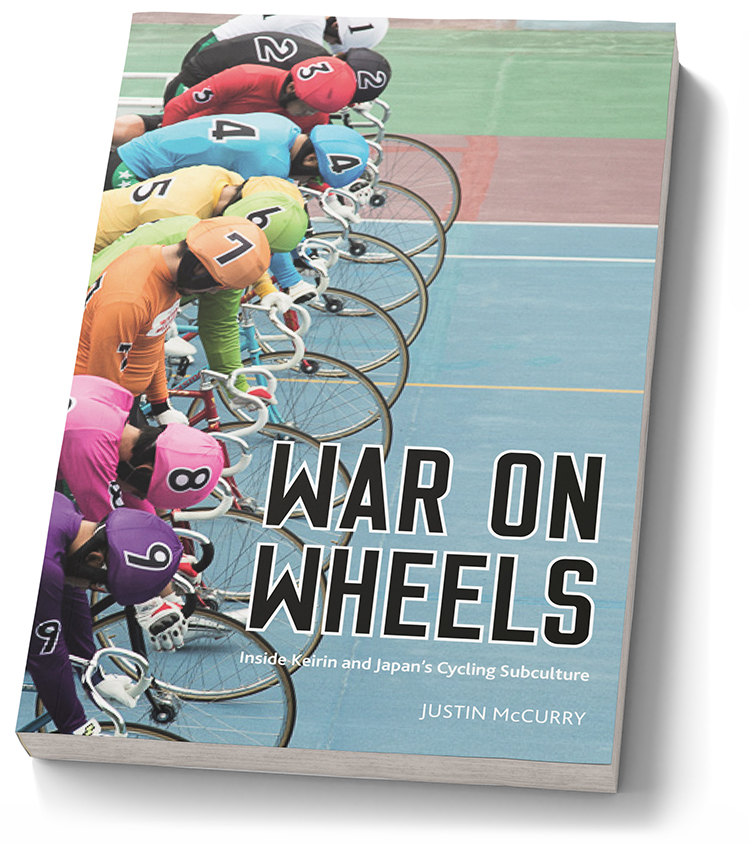

War on Wheels, the new book by Japan correspondent for The Guardian and Observer Justin McCurry about the uniquely Japanese version of the sport of keirin (bicycle sprint racing on a steeply banked circuit track just a few hundred metres long), is a tour de force that is as fast-moving and powerful as the highly trained riders it describes.

Throughout the book, the author brilliantly interweaves his description of one climactic end-of-season Grand Prix race—for a million-dollar first-place prize—into a fascinating survey of modern Japanese history. He places the development of the sport (and cycling in general) in Japan within the context of the nation’s tumultuous development over the past 150 years.

ACUMEN has two signed copies of War on Wheels to give away.

To apply, please send an email to: publisher@custom-media.com

The winners will be picked at random.

Japanese history

Bicycles first appeared in Japan in the early years following the Meiji Restoration in 1868, as the nation emerged from feudalism and quickly modernised to become an industrial and military powerhouse. When World War I curtailed European imports, the fledgling Japanese bicycle manufacturing industry swiftly adapted to meet growing demand.

Amid the urban devastation in the aftermath of World War II, keirin was conceived as a means of philanthropically raising money to aid destitute survivors. It also enabled municipalities to raise much-needed funds for rebuilding local communities by making use of proceeds from gambling receipts at the tracks. Despite initial opposition—and a rocky start that saw occasional crowd violence—the idea soon proved its worth after legislation had quickly been enacted to circumvent Japan’s official legal prohibition on gambling. Velodromes were soon constructed throughout the country, and blue-collar fans flocked to the new venues.

Contact sport

Due to its association with gambling, however, and the concomitant suspicion of yakuza (organised crime) involvement, the sport has long suffered in terms of public perception. It has never attained the widespread respect and acceptance accorded to baseball, football, sumo wrestling, or even universal approval in government circles.

Although the sport is not unique to Japan, having originated in Denmark, the Japanese version has several distinct characteristics that distinguish it from the international version:

- Competitors ride fixed-wheel (single-gear), steel-framed bikes with no brakes

- Within the nine-man race field, riders form ad-hoc 2-to-4 member teams, or “lines” (usually based on regional affiliation) and collaborate in the initial stages, before going it alone over the final lap and a half

- There is a strict hierarchy consisting of six classes of rider, with promotion and demotion determined by performance during the season

- For ease of identification, riders wear uniform jerseys in prescribed and vividly contrasting colours, with insignia on their shorts denoting the rider’s status within the sport

- Keirin’s funding and very existence are dependent on gambling, with proceeds helping to fund public works and relief programs

- There is often significant physical contact, even head-butting, between riders jockeying for position late in the race, such that star Australian competitor Shane Perkins (one of very few foreign riders invited to compete in Japan) has dubbed Japanese keirin “boxing on bikes”.

Tellingly, in Japan the name of the international version of the sport is written in nondescript katakana ケイリン, while the kanji 競輪 (implying intense competition on two wheels) are used to denote the Japanese version.

Keirin race on the Omiya Velodrome in Tokyo

Highs and lows

The author brilliantly ties in the fluctuating fortunes and development of the sport with key periods and events in Japan’s post-war evolution: economic reconstruction; the bubble era of the latter half of the 1980s; the subsequent lost decades of economic stagnation; the aftermath of the 2011 earthquake, tsunami and nuclear meltdown at the Fukushima Daiichi power plant; and the demographic time bomb facing Japan with its shrinking and ageing population.

This meticulously researched book features interviews with key figures, including top competitors past and present, leading coaches, and revered bicycle-building craftsmen. The author peppers his writing with astute observations on Japanese mores and society, throws in illuminating comparisons to Western frames of reference, such as football and gangster movies, and includes such humorous trivia as the fact that keirin legend and 10-times world champion Koichi Nakano, whom he interviews in-depth, once featured in a 1990s TV commercial for men’s wigs.

Describing the official keirin riders’ school at Shuzenji, Shizuoka Prefecture, McCurry paints a vivid picture of the spartan 11-month training period that Japanese would-be riders must undergo to obtain their keirin licence, in an austere and gruelling environment more akin to that of a traditional martial arts school.

Indeed, the description of keirin serves as an allegory for Japanese society overall. Its more noble aspects exemplified by the sacrifices younger riders make to help more established senior teammates in the line, while the pointed sexism regarding women’s involvement in keirin and resistance to encroachment by foreign riders underscore less palatable aspects of the Japanese condition.

Like Japan itself, the sport of keirin faces a highly uncertain future. Can it adapt, re-invent itself and thrive—or will it sink into irrelevance and terminal decline, a shadow of its glorious former self?

If you love Japan, cycling, sport in general, or modern history, you will certainly enjoy this highly informative and vastly entertaining book.

Phil Robertson is a keen cyclist and regularly participates in the annual Knights in White Lycra fundraising event: a four-day, 500km cycle ride ending up in northeastern Japan. This year, 43 amateur cyclists of all ages and abilities, from 13 countries, will participate to raise funds and awareness for the non-profit organisation YouMeWe.

Phil Robertson is a keen cyclist and regularly participates in the annual Knights in White Lycra fundraising event: a four-day, 500km cycle ride ending up in northeastern Japan. This year, 43 amateur cyclists of all ages and abilities, from 13 countries, will participate to raise funds and awareness for the non-profit organisation YouMeWe.

The charity helps marginalised children living in institutional care to learn essential career skills, such as creative problem-solving through coding and design challenges, all well suited to working in the digital age. Together with their employable skills, they also gain new levels of confidence.

The ride was cancelled in 2020 due to the coronavirus, and this year there are plans for the ride—which usually takes place in June—to be held in October, if the pandemic permits.

Social distancing measures would be employed, with the riders split into small groups, and each participant required to show a negative PCR test before the event.