When Prime Minister Shinzo Abe called for new carbon emissions targets at the 21st United Nations Climate Change Conference in Paris earlier this month, he may not have been aware that, back in Tokyo, one of the world’s biggest firms was already leading by example.

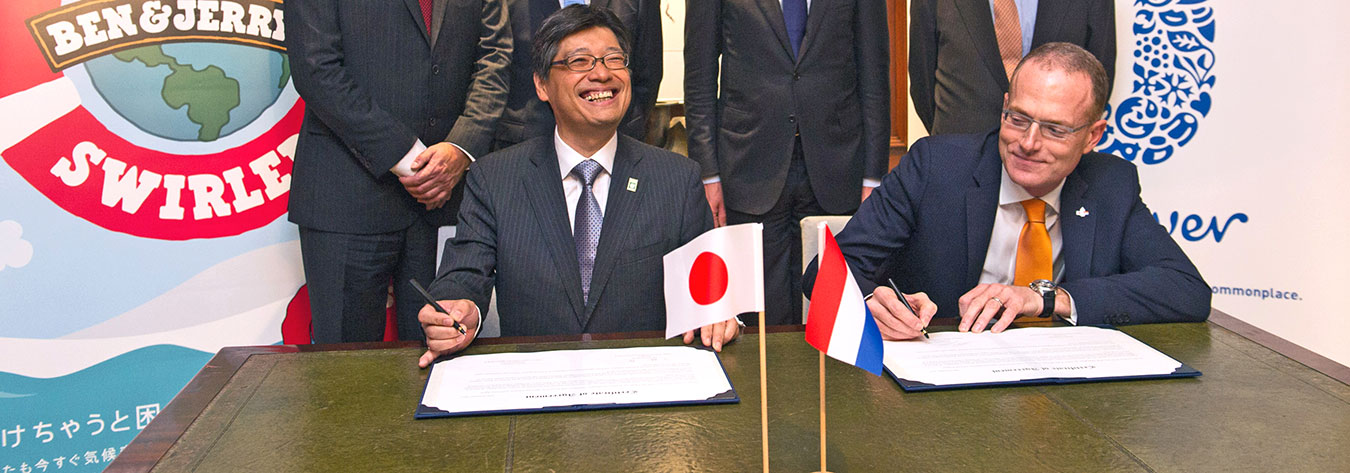

On 1 November, the Japan division of Unilever, the Anglo–Dutch multinational consumer goods company, became completely carbon-neutral in its domestic operations. It now replaces its domestic energy consumption in Japan with equivalent investments in local renewable sources.

Unilever first had to calculate the carbon footprint of its Japanese operations. These include the head office in Nakameguro, five sales offices across the country, two factories (in Shizuoka and Kanagawa prefectures), two Lipton tea shops in Kyoto and Ginza, four Ben & Jerry’s ice cream parlours, and every ice-cream freezer of the brand in Japan. The combined energy use amounts to 3,600 tonnes of carbon per annum.

The firm then matched this total with an equivalent amount of renewable energy that it feeds back into the national grid. This is done via the Japan Natural Energy Company Limited (JNEC), which buys power from a range of domestic sustainable suppliers.

“We’re still taking electricity from the same power lines supplied by Tepco and Chubu Electric, but the feed into those power lines is coming from a natural source”, said Andrew Bowers, Unilever Japan’s supply chain director. “There’s an energy farm that’s inputting renewable energy at the same rate that we’re consuming it”.

Unilever is one of the first firms in Japan to make its domestic business completely carbon-neutral, Bowers believes. “We know that other corporations have similar schemes, but we couldn’t find anyone else who is using renewable energy for their entire domestic operations”, he said.

The scheme builds on an earlier commitment, also achieved this year, to recycle all Unilever’s non-hazardous waste. Now, none goes to landfill.

“This is not a global off-setting scheme”, Bowers added. “We are investing in infrastructure in Japan that directly feeds what we consume from. We are also actively working to reduce our consumption of energy to ensure more people have access to renewables and that overall grid capacity is not reduced”.

Japan’s commitment to climate change targets has been under strain since the 2011 Fukushima disaster, when its entire nuclear industry was shut down and nuclear energy was replaced by fossil fuels. Despite this, environment ministry data shows a 3% fall in Japan’s greenhouse gas emissions for the financial year that ended on 31 March, 2014. This was thanks to a national energy-saving campaign.

In Paris, Abe committed Japan to developing “revolutionary technologies” for storing and generating renewable energy, with the details to be outlined in a new energy and environment innovation strategy in the spring.

In November, Paul Polman, Unilever’s global chief executive, announced that, by 2030, the firm would source all its energy worldwide from renewable grid sources. Bowers said that the Japan operations are “15 years ahead of Unilever’s global aspirations”.

From next year, all Unilever Japan products manufactured in-house will carry JNEC’s green power logo. However, this only accounts for 32% of Unilever items sold in Japan, as the rest are imported or contracted to other factories. These third-party suppliers are Bowers’ next target. If the extended supply chain can be brought to comply, 90% of Unilever’s products sold in Japan will be carbon-free. The firm hopes the remaining balance of imported items will catch up through its global commitments.

“It’s a small cost for a large investment in the world”, Bowers told BCCJ ACUMEN.

Eventually, he wants to work with the wider industry and hopes Unilever’s efforts will prove contagious. “I don’t want to use this as a competitive angle”, he said. “I want it to be a catalyst for change”.