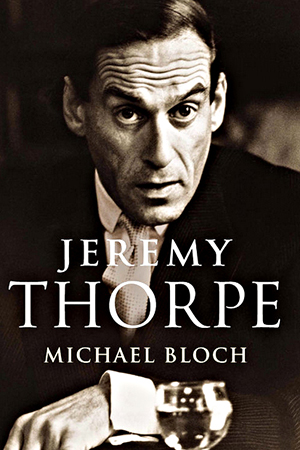

Little, Brown • £25.00

Thorpe was born into a life of privilege. The son and grandson of Conservative MPs, he turned away from their politics and embraced the values of the Liberal Party, which he led from 1967 to ’76. During this time, the Liberal Party made a number of advances and, in the general election of 1974, won some 6mn votes.

Neither the Conservatives nor Labour had a decisive majority, so Thorpe was in a very strong position. Conservative leader Edward Heath KG MBE offered him a Cabinet position if he would bring the Liberals into a coalition. But Thorpe’s price for doing so—electoral reform—was too much to swallow for Heath, who resigned in favour of a minority Labour government.

This was arguably the high point of Thorpe’s political career, for soon afterwards rumours began to spread of his involvement in a plot to kill Norman Scott, a stable boy and former model with whom he had had an ill-advised relationship in the early 1960s.

Scott boasted of what he called an “affair” with Thorpe, and claimed he was treated very badly in it. This gave rise to a situation in which Thorpe was making regular payments to Scott. Thorpe eventually entered into a bizarre plot to shut him up for good.

But the chosen assassin only managed to shoot Scott’s dog.

Gradually, as public awareness of the circumstances grew, Thorpe was obliged to resign as leader of the Liberals, and lost his North Devon parliamentary seat, which he had held since 1959. He went to trial at the Old Bailey in London, charged with conspiracy to murder. While he was acquitted on all charges, the case ended his political career.

Bloch tells this story in a gripping way, but he puts it into the much broader context of Thorpe’s life and career, highlighting the many achievements of one of the most fascinating figures in British post-war politics.

Thorpe was a showman: a flamboyant exhibitionist whose sharp wit and talent for mimicry made him many friends (and some enemies). But he was, undeniably, a successful parliamentarian. He was fiercely opposed to Ian Smith’s regime in Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe)—as he was to apartheid—and strongly in favour of human rights issues, including gay rights in the UK. He was a great believer in the Commonwealth and worked with Heath in relation to Europe, where he believed there should be integration.

As well as highlighting these aspects of his life, Bloch’s engaging biography demonstrates time and again how the urge to take risks was always there, threatening to precipitate a fall, as of course, it eventually did.