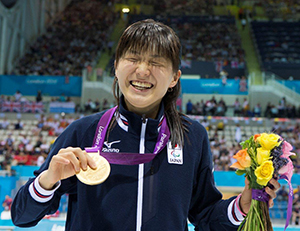

Rina Akiyama won a gold medal in the 100m backstroke at the 2012 Paralympics.

Attitudes to physically impaired people have improved as a result of the London 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games. That is according to 68% of 10,000 individuals surveyed by the UK’s Department for Work & Pensions in 2014.

At the time, Mike Penning, then-minister of state for disabled people, said the Games had “helped lead to a transformation in the representation of, and attitudes towards, people with disabilities in Britain. It challenged mind-sets and left a positive lasting legacy”.

Paralympic equestrian Sophie Christiansen is among the athletes who agree. “London 2012 not only inspired a generation”, she said, “it challenged the ideas of a generation about what disabled people [are] capable of”.

So why was London 2012 successful in creating such a positive legacy of social change?

According to Manami Yuasa, head of arts at the British Council Japan, it wasn’t coincidental. Aside from a physical legacy of improved transport, facilities and services for all members of society, the organisers of London 2012 wanted to integrate the two Games.

Central to the delivery of the Paralympics, in particular, was the goal of transforming people’s attitudes to disability, thereby boosting the confidence of people with physical impairments.

Yuasa was speaking at a British Chamber of Commerce in Japan event on 25 March, along with three Paralympians currently working for GlaxoSmithKline K.K. (GSK). The athletes attributed London’s success to the fact that its Paralympic Games were about ability rather than disability.

“The Paralympics was accepted as a sports event—and the Paralympians as athletes”, said Rina Akiyama, who won gold in the 100m backstroke in London. “There was real interest. Sometimes the tickets to the Paralympic events sold out before the Olympic ones”.

Moreover, while the Japanese media tends to cover disabled athletes primarily in terms of success stories of people who have overcome a physical condition, the coverage of the London Paralympics had sports as its core; the Paralympians were not given special treatment.

Ice sledge hockey Paralympian Daisuke Uehara

Daisuke Uehara, who took a silver medal in ice sledge hockey at the Vancouver 2010 Paralympic Games, agreed, adding that the principle applies to the population, too. He said spectators should “be moved by people winning in sports, not by them overcoming a disability”.

People used to tell snowboarder Hisano Tezuka—who competed in the last two Deaflympic Games in 2011 and 2015—that it was dangerous for her to participate in sport because she cannot hear. But, since London 2012, she said that attitude has changed.

A key message from the panellists was that individuals with physical impairments are like anyone else; they should be thought of as differently abled, rather than disabled. “Only our consciousness is needed to change negatives into positives”, Uehara said.

Akiyama said that children often set the best example. When she began swimming lessons at a young age, her coach told the other children in the class to take care of her by taking her hand while walking to the pool and telling her she was nearing the pool wall before she swam into it.

“I saw that children learn and adapt; they know how to provide support and can judge to what extent it is needed”, she said. “They created a comfortable environment for me”.

While the athletes suggested people’s behaviour towards the physically impaired is probably partly rooted in a desire to protect them, they said engagement is preferred.

“Don’t decide on your own that someone in a wheelchair, or who is blind or deaf, can’t do something. Ask that person”, said Uehara. He believes children who have physical disabilities need to be given more freedom and opportunities to build their confidence.

A Paralympic Games can bring these issues and more into the spotlight through not only sport, but also culture. As part of the 2012 Cultural Olympiad, Unlimited—a programme to promote deaf and disabled artists from the UK—was delivered by London 2012, Arts Council England, Creative Scotland, Arts Council of Wales, Arts Council of Northern Ireland and the British Council. It commissioned 29 pieces of work to support new art, provide mentoring and build ties between artists in the UK and abroad.

“It was an opportunity to build the artists’ confidence”, Yuasa said. “Before the project, artists didn’t have equal opportunities to apply for public funding but, since 2012, the number of grant applicants is increasing. People now know of these wonderful artists. The audience’s perspective of disability changed”.

Unlimited generated interest nationally and internationally. The British Council supported five collaborations with artists across four continents. Such was the programme’s success that it was extended three years beyond its allocated duration, with work to include a festival at the Southbank Centre in London later this year.

Though undoubtedly successful, Yuasa said projects such as these alone cannot change society. Instead, they may act as a springboard or catalyst—and building on any improvement achieved is vital. Uehara agreed, explaining that 2020 should “be the start, not the goal”.

The panellists applauded the use and development of integrated facilities for Olympic and Paralympic athletes. Akiyama said that training in the pool alongside Olympic athletes had been an inspiration, as they told her she had been to them.

For the general public, too, integration was favoured, as well as greater availability of activities in which people of any ability can take part, such as blind soccer or wheelchair basketball. This would improve interaction, understanding and, ultimately, inclusion.

Deaflympian Hisano Tezuka got a government award.

Tezuka recalled the 16 years she had spent at a workplace without access to an interpreter, and unable to understand what was going on. She called on the audience to make their places of work comfortable for people of all abilities, as she tries to do. People may then naturally apply this attitude to other public spaces, too.

“Create an environment in which people can move easily, without assistance and with peace of mind”, she said. “Tokyo 2020 visitors may then also have that experience.

In terms of infrastructure, Japan is more advanced than other countries in its provision of barrier-free services for blind people, according to Akiyama. She pointed out the tactile paving strips marking the way at stations, and the voice announcements in lifts.

However, in her experience, Japanese people are reluctant to offer help unless they believe a blind person is in danger. She was pleasantly surprised by the assistance she has received overseas, despite the poorer infrastructure.

“Japanese people are very reserved sometimes; I think their barrier is in the mind”, she said.

Uehara said Japan needs to consider the purpose and usability of each facility. “There may be a ramp at an entrance, but it is so steep that no one can use it”, he said, adding that “in Japan, the important thing is that there is a ramp”.

Matt Burney, director of the British Council Japan, said firms have a responsibility to carry out audits of their premises to ensure they are accessible. In addition, any events they organise should be able to accommodate people with physical impairments.

Addressing firms interested in supporting Tokyo 2020, he said, “it is important for companies not to see the Paralympics, in particular, as part of a corporate social responsibility agenda, because I think that speaks to the charity model of disability”.

Similarly, Jim Fox of GSK said that, rather than viewing the Paralympics as part of its CSR work, the firm considers it “an opportunity to engage and motivate our employees all over Japan, to source volunteers and to raise awareness”.

Audience members and speakers called for firms and individuals to share ideas and best practice in relation to work for Tokyo 2020. The takeaway was that much needs to be done for the Games to promote diversity and inclusion—and London 2012 can be a useful model.