Hiromi T. Rogers, at the Foreign Correspondents’ Club of Japan

Settling in a new country and adapting to a foreign culture often can be arduous. Difficulty in communication, lack of familiarity with the environment and having no acquaintances are what most emigrants experience to some degree. For Hiromi T. Rogers, settling in the UK was just that. But through the legacy of William Adams, she was not only able to relate but also share his influential story with others in similar situations through a book.

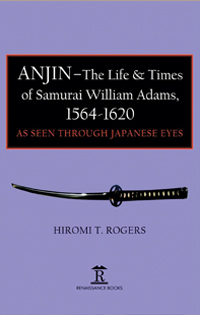

In 2016, Rogers published ANJIN: The Life and Times of Samurai William Adams, a narrative of the first British man to set foot in Japan. Although her book is not the first to be written about Adams, also known as Miura Anjin, it is the first to incorporate information from both Western and Japanese sources. In it, Rogers follows Adams in great detail on his expedition to Japan and describes how an ordinary British man climbed the strict Japanese hierarchy to eventually earn the status of a samurai.

When Rogers moved to Devon, England, she attended the University of Exeter to earn a PhD in drama. Her paternal grandmother, whose ancestors were samurai, was fascinated by films and dramas depicting the Edo period. This interest was passed on to Rogers from an early age, along with a keen interest in the culture and language of the Edo period.

At first, she had no intention of writing a book about Adams and was merely researching his life story while looking for inspiration and encouragement to survive the drastic transition from home.

Just as Adams had arrived as the sole English-man in Japan, Rogers had arrived as one of the few Japanese women in Devon. Although similar in situation, Rogers found refuge in the fact that, compared with Adams, she was in a much better situation and living in better times.

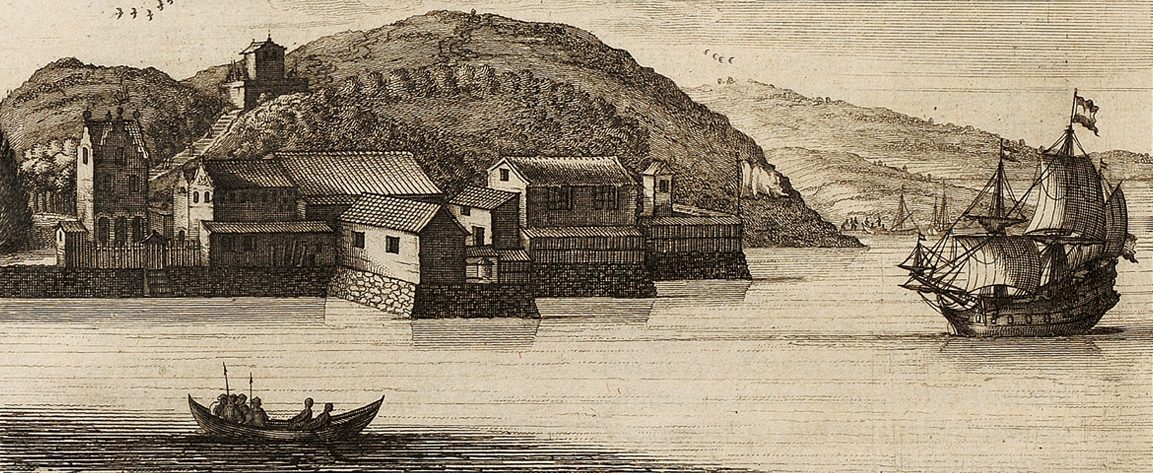

Part of Adams’ ship had been stored for centuries at Ryukoin Temple.

Extraordinary things

From the moment Adams set foot on the ship De Liefde with the Dutch East India Company, to when he arrived in Usuki, Japan, in 1600, his life had been at stake.

What Rogers found inspiring was that, despite the risks, Adams had not only managed to be assimilated into the local community, but also to earn the trust of Japan’s lords. Adams was not an extraordinarily fearless person either. As Rogers said, “He is no different from ordinary people, he looked strong, but inside his emotions were sometimes very fragile. He wanted to give up sometimes but he has done extraordinary things.”

When Rogers shared the story with her English friends, they were fascinated and encouraged her to write short stories and articles on Adams. She then proceeded to draft a book and approached various publishers to see if they were interested.

Due to existing publications about Adams, many turned her down, but eventually she was advised to contact Renaissance Books, a British academic publisher. With some agreements reached to change the style, they decided to take on the book.

Erasmus is displayed at the Tokyo National Museum.

Rogers bases the narrative on real accounts and evidence from Japan, England, the Netherlands, Spain and Portugal and on what she calls likely scenarios. She said: “My purpose was to make Anjin better and widely known outside Japan to English-speaking readers and also generally, not only to academic readers”.

“William Adams didn’t write so much about himself in his diary. So as a researcher, I had to learn many things from people around him.”

But in the case of attaining sources from Japan, Rogers said it was a much more complicated process. Especially during Tokugawa’s rule, primary sources were commonly destroyed to avoid information finding its way into the wrong hands. Instead, information was shared orally or, for ninja, through code. Any evidence that does remain can be found in temples. Consequently, Rogers found information that other writers and historians could not, by visiting Japanese temples and hearing their stories.

Erasmus

During her research, Rogers unexpectedly came across a tie between her maternal ancestors and Adams. Her great grandfather was part of the Tsuchizawa family and was titled the Lord of Omi Castle in Sano City. This happened to be not far from Tochigi Ryukoin temple, where part of the stern of Adams’ mostly destroyed ship, De Liefde, had been stored for more than 400 years.

The part is in the form of Erasmus, a Dutch scholar, and was passed on as a gift from Adams to Tokugawa Ieyasu and, finally, to Makino Shigezumi, who brought the figure to his family temple, Tochigi Ryukoin. Today, it is displayed at the Tokyo National Museum in Ueno, with a replica in the Netherlands.

Rogers believes that her ancestor had even encountered the figure due to his acquaintance with Makino and his involvement in high-ranking meetings. She said: “It was particularly poignant for me to discover that the friendship between Makino and Lord Omi meant that my ancestor would almost certainly have been shown the prized Erasmus.” Furthermore, when Tokugawa conquered west Japan in the Battle of Sekigahara in 1600, they ordered all western lords to be executed. But because of Makino’s previous devotion to the influential lord Ikeda Terumasa in the east, he and the western lords around him, including Rogers’ ancestors, were spared their lives.

Rogers’ book is based on real accounts.

In Japan, one often hears talk of Adams, but his full story is not widely known. Even in Hirado, Nagasaki Prefecture, where Adams is believed to be buried, Rogers says that the locals do not know what really happened. “It doesn’t mean they aren’t interested. They are interested, they just didn’t know.”

Recently, Rogers said that cities in which Adams lived, such as Hirado and Yokosuka, have been making efforts to publicise Adams and hoping to promote tourism in their areas through his legacy and local monuments honouring him.

Having received a positive reaction from English readers, Rogers is looking for ways to publish a translated version of her book in Japan in time for the 400th anniversary in 2020 of Adams’ death.

Rogers hopes more people will learn about Adams and develop an interest in history. “During my time in school, my generation didn’t respect history so much. But I always found it not right, we mustn’t neglect learning history because our existence is always connected with history.” She also hopes to dramatise her book in Japan and the West, as she feels it is a story that can be enjoyed internationally.

Since writing her book, Rogers has been continuing her research. She is hoping to write a book about Matsura Shigenobu, who helped Adams during his time in Japan. She has also been doing further research on the origins of overseas trade in Japan through Kyushu, even before Adams’ arrival and hopes to put together some of Japan’s undocumented history from more than 1,000 years ago.