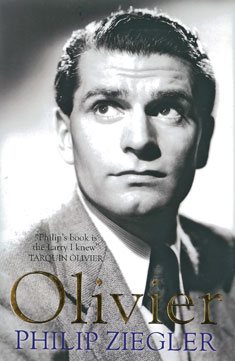

Biography of Laurence Olivier digs into actor’s personal life

As a child, Laurence Olivier (1907–89) claimed he wanted to become the “greatest actor in the world”.

For many, he fulfilled that ambition, and there are numerous biographies that bear out that contention. So many, in fact, that it is worth questioning why Philip Ziegler and his publisher thought it worthwhile turning out another.

In truth, this new biography reveals nothing that has not been discussed before when it comes to Olivier’s career. Still, it looks far more closely at his personal life and the demons that drove him.

The book is wonderfully crafted; Ziegler has a fine ear for detail and writes with great clarity and expression, making the biography a compelling read. Even at almost 500 pages, the pace does not flag and the reader is not overtaxed.

Olivier’s dazzling career is recorded in meticulous detail: the disappointments are recounted as well as the triumphs. His championing of London’s Old Vic Theatre and repertory company, and his determination to see through the establishment of the National Theatre, are soundly charted.

The latter endeavour was not by any means an easy row to hoe, and the reader is left in doubt as to the debt the nation owes. It is so easy, today, to take the South Bank for granted as a centre for theatrical excellence.

The struggle to set it up, however, and create the company that would populate it, would prove to be as challenging and dramatic as much of what would later be presented on its stages.

Olivier would have been unable to pursue so much of his stage ambition—not to mention his comfortable lifestyle—if it had not been for his lucrative film career.

This, too, Ziegler explores in some detail, including the Hollywood box-office hits as well as Olivier’s own (successful) attempts at directing some of William Shakespeare’s greatest plays.

Through this discourse we learn a good deal about Olivier’s relationships with some of the other greats of the era. Here are John Gielgud, Ralph Richardson, Michael Redgrave and Alex Guinness, all rivals to some degree and yet he worked with every one of them.

Memorably, he and Gielgud alternated the parts of Romeo and Mercutio in Shakespeare’s tale of star-crossed lovers. We can only lament that there were no means to capture such performances on film or otherwise in those days. The shows were, by contemporary accounts, outstanding.

Nevertheless, Olivier’s relationships with his peers were not always smooth; he admitted such in one exchange: “You know what a c— I can be”.

Where Ziegler’s biography truly breaks new ground is in discussing Olivier’s personal life. His first marriage to Jill Esmond resulted in a son, Tarquin. By his own admission, Olivier was a delinquent father.

He was also an inconstant husband. Throughout his life Olivier indulged in numerous affairs with his leading ladies and others, and those accounts are examined appropriately.

His second marriage to Vivien Leigh is quite rightly explored in great depth and with great sensitivity. She was extremely beautiful and very talented, but increasingly suffered from clinical depression over the years of their union.

Ziegler paints a powerful portrait of the way in which the couple sought to maintain an outward picture of domestic bliss while dealing with mutual infidelities and a deteriorating hold on reality.

Finally Olivier is rescued by his relationship with Joan Plowright—his third wife, Lady Olivier—but even then he appears unable to remain faithful.

This is—in the clichéd term—a warts-and-all biography. It serves its subject well by and large, but it is fair to say that Olivier does not emerge as a likeable man.

What is also true is that for someone who played so many roles with which people can strongly identify—Archie Rice, John Tagg and Henry V among others—we do not really get to know Olivier himself. But that should not come as a surprise; those who worked most closely with him claimed the same. He even said it of himself.

Olivier could walk down a street and not be recognised: he looked like a banker or someone from the city. And yet, when he walked into a room that mattered to him, he turned heads and electrified it.