- UK–Japan trade deal should be top-four priority

- EU–Japan deal complicates trade talks

- Productivity growth remains key for UK economy

Lord Green of Hurstpierpoint at the British Embassy Tokyo

But those flows are now being reconfigured, with the UK’s vote to leave the European Union (EU) last year casting uncertainty over its relationship with major trade partners. During a visit to Tokyo in March in his capacity as chairman of the Natural History Museum’s board of trustees for the launch of the museum’s Treasures of the Natural World exhibition, Green sat down with BCCJ ACUMEN to discuss his personal views on Brexit’s implications.

Look east

Many arguments in favour of Brexit were predicated on the notion that the UK should be more active in pursuing trade with emerging economies, such as India and China, and existing Commonwealth partners, something that Brexit proponents claimed was hamstrung by EU membership. While Green acknowledged the economic size and clout of the aforementioned Asian giants, he pointed out that Japan ranks alongside them in terms of potential trade and investment opportunities for the UK.

“I think that sometimes people forget to remind themselves of the fact that Japan is the third-largest economy in the world”, said Green. “It may not have been growing very rapidly in the last three decades, but [the economy is still that big]—it’s not only the third largest, it is of course one of the most sophisticated economies in the world and a big investor in Britain”.

Although Lord Green does not think there will be any “particular sticking points”, the terms of a post-Brexit trade deal with Japan won’t be straightforward, and again the EU plays a significant role.

“Life is complicated by the fact that the EU is in the process of negotiating a deal with Japan, and what the British government will have to do in its negotiation is to think carefully about the implications of a possible EU–Japan deal”, he said.

That is because any EU–Japan deal that eliminates or minimises tariffs will change the calculations and trade-offs for Japanese investors using the UK as a base for exporting to the single market. That, in turn, will affect the kind of deal that will be appealing to the UK and Japan when it comes to their own deal.

“If that sounds complicated, it is”, he added.

One of the other issues facing the UK, Green went on to explain, is its capacity to negotiate several trade deals at once, with the administrative and political capital needed to pass such agreements meaning that some will have to be prioritised over others. But he was clear on where Japan fits into this hierarchy.

“Japan is clearly within the top three or four highest priorities”, he said.

Right skills

But trade isn’t just about striking agreements—you also need the goods and services that people want to buy. To bolster the British economy, Prime Minister Theresa May has resurrected the concept of an industrial strategy. It’s an approach with which Green agrees.

“I do think industrial strategy matters”, he said. “What exactly is in an industrial strategy? There’s plenty of scope for debate about that and time will tell. What I think is commonly agreed—and I certainly believe to be true—is that Britain needs to invest very strongly in its skills base.”

Analyses of Brexit typically identify one of the causes as being a feeling by part of the population of being economically left behind, something that Lord Green feels would be alleviated by proper training.

“The development of a much more proactive policy framework for investing in apprenticeship systems, in technical education, vocational training—so that there are clear pathways to the skilled jobs that the manufacturing sector needs—is a high priority for Britain, because frankly for the last 30 to 40 years … we’ve neglected this and we’ve paid the price for that in terms of a decline in the manufacturing industry as a percentage of the British economy, which is steeper than has been seen in all of our obvious competitor or analogous countries”.

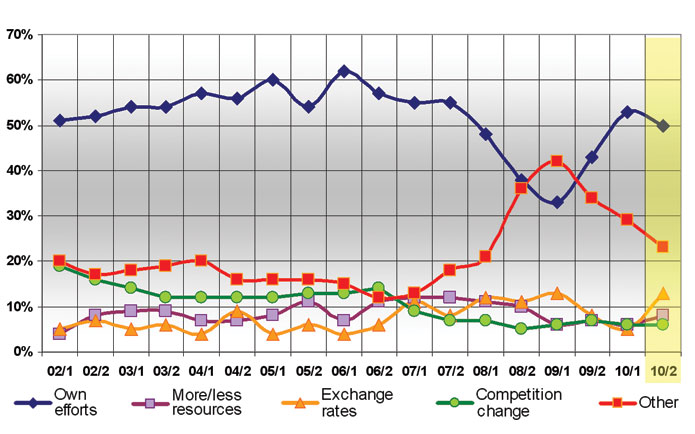

All of this links into productivity, which has seen little growth in the UK since the financial crisis. According to the Office of National Statistics, productivity increased 0.4% from the second to the third quarter of 2016, well below the pre-financial crisis average of 2.1%.

“That’s the sign of a non-inclusive economic growth model, and we’ve got to get away from that”, he said.