By Eiichiro Tokumoto

Translated by Mark Schreiber

An excerpt from an article originally published in the 12, 19 November, 2020 issues of the weekly news magazine, Shukan Shincho.

“My great grandfather did organise the Meiji Restoration. But I’m a merchant and am much more interested in what business can be done today”.

On 3 July, 2019 at a house in a quiet residential area in the City of Westminster, close to the Houses of Parliament, the elderly man looked back nostalgically on the past. As bright sunlight streamed into the window, in a quiet, carpeted room, time seemed to stand still. Seated on a sofa, with his back toward the window and holding a cane to his side, he began speaking in a modulated tone. He resembled the classic image of a good old man.

“When Chinese burned the opium, we asked the British government to send gunboats to destroy and punish them,” he said. “And the reparation treaty and Hong Kong—we don’t justify or pretend that it didn’t happen. It’s unfortunate history and, at that time, the standard was quite different”.

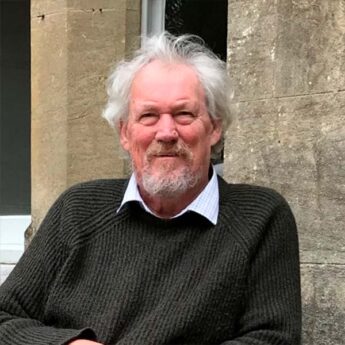

Sir Henry Keswick: “Our policy is to do long-term, right decision”. PHOTO: EIICHIRO TOKUMOTO

His name was Sir Henry Keswick, and he was 80 years old. One of the wealthiest individuals in Britain, he held the title of chairman emeritus in the multinational conglomerate Jardine Matheson. For many years, he had been a “good friend” enjoying close ties with Taro Aso, the deputy prime minister and minister of finance in the cabinets of Japan’s two most recent prime ministers, Shinzo Abe and Yoshihide Suga.

The Jardine Matheson trading firm was established in Guangzhou (Canton), China in 1832 by a pair of Scottish traders, William Jardine and James Matheson. Initially, the firm had traded in Chinese tea and Indian opium. When China’s Qing rulers banned the illegal trade in opium and ordered the stocks to be destroyed in 1839, Britain’s Parliament ordered the Royal Navy to mount a punitive expedition the following year. The events are known as the first Opium War, which continued until 1842.

The Chinese forces were soundly defeated, and Hong Kong was ceded to Britain. From its new headquarters in Hong Kong, Jardine Matheson subsequently expanded into other fields, including shipping, transport, finance and real estate, eventually becoming a multinational conglomerate. The firm’s presence in Japan predated the beginning of the Meiji Period, and it helped to arm the powerful clans of Satsuma and Choshu with modern weaponry that enabled them to overthrow the Tokugawa shogunate. Therefore the firm can be said to have played a behind-the-scenes role in bringing about the Meiji Restoration.

Jardine Matheson can truly be said to have changed the course of world history. Control of the firm later moved to the Keswick family, and the gentleman seated before me, Sir Henry, was the fourth-generation Keswick to head the firm. Starting in Yokohama in the mid-19th century, family ties over several generations led to the present ties to Taro Aso. These extend back through Aso’s mother, Kazuko, who was the daughter of former Prime Minister Shigeru Yoshida.

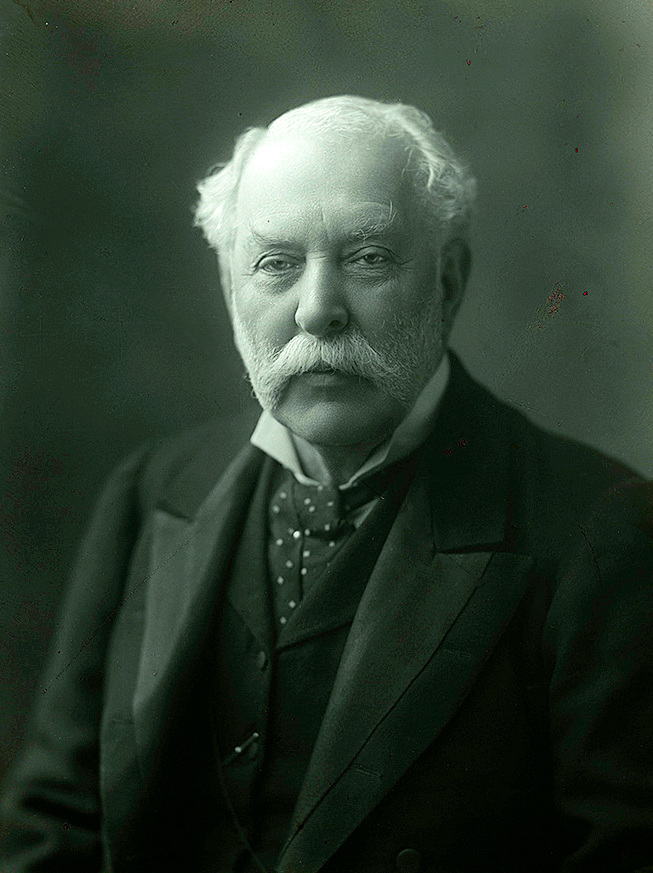

William Keswick

Arrival in Japan

In July 1859, the schooner Troas arrived in Yokohama. From it disembarked a young Scottish man named William Keswick. Some years earlier, he had travelled to China and taken up employment at Jardine Matheson.

In August 1858, five years after the US Navy’s East India Squadron, under the command of Commodore Matthew C. Perry, had forced the opening of Japan to US trade, Britain concluded the Anglo–Japanese Treaty of Amity and Commerce. Foreign merchants, full of the spirit of adventure and ambition, flocked to Japan. Among the first to arrive was Sir Henry’s great grandfather, William Keswick. The office he opened in Yokohama for Jardine Matheson was called Ei Ichiban-kan (English House Number 1).

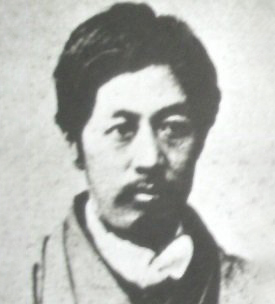

Kenzo Yoshida

By autumn 1868, the year of the Meiji Restoration, the port of Yokohama had been transformed into a thriving mercantile centre with rows of Western-style brick buildings. Kenzo Yoshida, a young retainer of the Fukui clan who had studied English in Nagasaki, took up employment with Jardine Matheson and, through lucrative transactions with the Japanese government, earned large remuneration. Kenzo was eventually to become the adoptive father of Shigeru Yoshida.

Kenzo left employment with Jardine Matheson and struck out on his own, becoming a highly successful businessman. But in 1889, at the young age of 40, he succumbed to illness, leaving a considerable fortune—equivalent today to some ¥3bn—to his adopted son, Shigeru, who at that time was only 11 years old. Shigeru, alas, completely squandered his inheritance. As Taro Aso was to write in a book about his family’s history:

“I was told that, after receiving his adoptive father’s inheritance, my grandfather lived in such regal splendour and was an eye-grabber. Even while a student, he owned a house in Tokyo and commuted to the university on horseback.

“My mother wondered what happened to the money grandfather inherited from the Yoshida family. She once told me, ‘I had tried to ask him about it, but ended up failing to do so.’ What became of the money will remain a mystery, but it’s safe to say that grandfather squandered it before entering politics”.

Young Shigeru was not in the habit of carrying a wallet and instead wrote out cheques for his expenditures. He also hated being treated by others, and always paid for frequent geisha parties out of his own pocket. This does not suggest that he squandered his entire inheritance on geisha parties, but the seed money of his inheritance had been received as a monetary reward from Jardine Matheson. If it was these experiences that bestowed Shigeru Yoshida with the sense of pride and nerves of steel that served him well as prime minister, then perhaps it can be said his free-spending ways proved to be a good investment.

Kawagoe clan

The long-standing mystery as to why young Kenzo wound up being employed at Jardine Matheson was solved with the discovery of declassified documents at the British National Archives in London. Just after the Meiji Restoration, when the city name of Edo was changed to Tokyo (Eastern capital), Kenzo Yoshida had been charged as complicit in a case of fraud. The case, involving the defrauding of a large amount of money, led to a major diplomatic spat between Japan and Britain.

It seems that in November 1870, the Yokohama office of Jardine Matheson received a business proposal from the Kawagoe clan, which at the time ruled the region around what is now Kawagoe City, in Saitama Prefecture. A man named Joichi Amano, who claimed to be the clan’s chief controller, placed an order to purchase a steamship. By the end of the year, a contract had been drawn up and the firm waited for receipt of payment from the clan. However, the entire transaction was fraudulent.

According to archival documents in the Foreign Office, the Kawagoe clan denied it had authorised Amano to enter into a contract on its behalf, and it appears likely that Amano was attempting to conduct the transaction to profit personally. Jardine Matheson petitioned Sir Harry Parkes, the British Consul General in Japan, to demand payment from the Kawagoe clan, which refused, and the dispute ended up being tried in a Japanese court.

Kenzo Yoshida, who had acted as interpreter for Amano, wound up being charged as complicit in the fraud. A record of Kenzo’s testimony in English remains, in which he told the investigator:

“I had previously heard from Joichi that [the steamship] was intended to carry on an extensive trade to Yezo (Hokkaido) and Osaka. I never heard before that Joichi was merely borrowing the name of the clan … I regret very much having interpreted so carelessly”.

Jardine Matheson had no cause for complaint against Kenzo Yoshida, whose only role had been translator. In spring 1872, the court ruled that the Kawagoe clan was not liable for the breach of contract. Amano was sentenced to two-and-a-half years’ imprisonment and seizure of his assets. Yoshida was let off with a light sentence: home confinement for a period of 30 days.

Modern day

The British Charge d‘Affaires who tried to arbitrate the dispute, in a report to the Foreign Secretary in London, wrote, “If the representative in Yokohama of the English firm had been a little more careful in his enquiries before he entered even into the preliminary contract with Amano Joichi, he would have found the real position of this man”.

This incident of 150 years ago was a learning experience for Jardine Matheson, which came to understand the importance of exercising due diligence when examining the credibility of potential customers. Given the fact that the firm hired Kenzo just after the fraud case, it would be natural to reason that Jardine Matheson hoped that he would play the role of advisor.

So, ironically, thanks to the confidence man called Joichi Amano, Jardine Matheson and Kenzo Yoshida were brought together, and the huge inheritance left to Shigeru Yoshida became the cornerstone of ties between the Yoshida–Aso family and the Keswicks. This lesson has come to span multiple generations.

“I have very good advisors,” Sir Henry told me. “Having clever people working for me is very important, and the whole Aso family are my personal friends. If we have a big problem in Japan, we might ask for Taro’s advice. Finance minister and deputy prime minister are very powerful positions. But we don’t have a big problem at the moment, as we do joint ventures with Japanese companies in Southeast Asia”.

In 2018, Sir Henry Keswick—the fourth in his family line since William Keswick, who had arrived in Japan at the end of the Edo Period—retired as chairman and was succeeded by his nephew, Ben Keswick. Rumours are that Taro Aso, who has also turned 80, will soon retire from politics. Among the potential candidates for Aso’s successor is his daughter, Ayako.

After graduating from the University of Tokyo, Ayako studied in Britain and subsequently wed a Frenchman. When Ayako visits Britain, the Keswick family looks after her.

“Ayako now lives in Paris, and we look after her when she comes to England. I have observed that Ayako is very smart and mentally tough. I would expect she will become a powerful politician and hope that one day she will be prime minister of Japan”.

Close to Yamashita Park on Yokohama’s waterfront is the Osanbashi Pier, a passenger terminal for luxury cruise ships. On the corner in front of the Silk Center stands a commemorative sign that reads, in English and Japanese, “Former site of Ei Ichiban-kan”. It marks the location of what was formerly the office of Jardine Matheson and testifies to the view that “what’s past is prologue”.