There is no doubt that the voices of women in business are growing louder in Japan. The pressing needs of an ageing population, with its related candidate-short labour market, is just one driver behind Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s “womenomics” agenda , and events such as the Global Summit of Women, which was held in Tokyo on 11–13 May, have been attended by the prime minister as he seeks to promote initiatives that will economically empower women. But how far have these initiatives actually been implemented?

On 19 April, BCCJ ACUMEN hosted a roundtable with Maiko Itami, marketing manager at EF Education First Japan K.K., Xue Wang, senior associate at Allen & Overy Tokyo, and moderator Jane Best OBE, chief executive officer of Refugees International Japan, to discuss the issues at hand. BCCJ ACUMEN also later sought the views of Rina Akiyama, a member of the GlaxoSmithKline K.K. essential training team, and Rachna Ratra, sales and marketing director at Robert Walters Japan K.K.

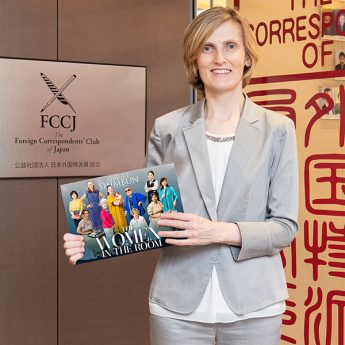

Chris Russell, editor of BCCJ ACUMEN, with the roundtable participants.

Mind the gap

According to figures from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, the 2016 employment rate in Japan for men stands as the third highest in the group behind Iceland and Switzerland, at 82.6%. But this sees a steep drop to 66.1% for women.

Both Wang and Itami believe that tackling ingrained gender norms, both on a societal and business level, is central to addressing the lack of women in business.

Much of this involves changing mindsets, which for Itami means having the confidence to grasp the opportunities.

This confidence does not come easily, and changing the mindset of a whole population of women is a tall order, but Wang stressed the need for a “critical mass” of women to be able to change mindsets and cultural norms.

“Is it the role of the women to do this?” Best asked.

“It’s not something that any one person should do”, said Itami, who added that instead there needs to be “a more collaborative way of thinking”, something that would involve the efforts of not just women, but also men.

Wang echoed this: “It’s not just women that need to champion the younger generation to bring about change. It’s the men that are currently running the show that really need to be the drivers for this”.

Looking after baby

In addition to a cultural shift, concrete government policies are also required and one key question that Best asked was: “Is the government doing enough?” The contentious topic of childcare is something both Wang and Itami believe is still a serious barrier for women wanting to return to work, and requires further work by the government.

Wang is expecting, and so is in a good position to assess the environment facing working mothers.

“That seems to be a huge barrier from what I hear, in terms of allowing mothers to go back to work when they want to because of the lack of childcare centres”, Wang said.

One way that the government is looking to tackle the shortage of childcare is by encouraging men to take a more active role in childrearing. The business community is also being pushed to enact changes to their paternity leave policies. But Wang believes that the message still isn’t getting through.

“I would like to see companies taking a more proactive role in promoting that, because astonishingly I’ve heard on many occasions—I’ve asked about it—the company doesn’t even know that these policies exist”, she explained.

Global goals

One thing that both Itami and Wang believe has played a huge role in their careers, and should be on the agenda for any woman wanting to go into business, is international opportunities. “How easy is it for Japanese women to find jobs, to find interesting jobs, where do they look for jobs and where do they network?” asked Best.

When choosing whether to begin a career at an international or Japanese firm, Itami explained, “the paths go in two separate ways”.

“If you have the chance to study abroad, or learn other languages, or know people other than Japanese people, then you will be more open-minded”, she added.

Indeed, education plays a significant role. Encouraging women to pursue careers, and providing them with the tools to do so from the start is crucial.

“The big Japanese corporations could be doing a lot more, because when they recruit out of university … what you often hear is that women naturally—I don’t know whether they gravitate towards it or they’re directed towards it—but they often take on more administrative roles rather than the business roles that really allow them to grow their career”, Wang said.

“Without allowing [women] on the path to start with, to actually take on more challenging roles, there is also no way for women to progress to leadership positions in those organisations”, she added.

In the view of Wang, there is a need for more female leaders in organisations—people who can then champion other women pursuing similar roles. Itami highlighted the need for women to take control of their opportunities and “grasp” them.

A lot boils down to the roles of women in leadership positions as both mentors and drivers of change in business norms. Because as Itami pointed out, “[the government’s] women in business agenda is kind of set and formed by men”.