Before he arrived in Japan and began to put paint to canvas, Anglo-American artist Tim Betjeman was well aware of some of the giants of this nation’s creative arts. Names such as Hokusai Katsushika, Hiroshige Utagawa and, more recently, Yayoi Kusama, have a global following and are much sought-after among galleries and collectors. A little over a year after entering Tokyo University of the Arts, Betjeman says he has become fascinated by all forms of Japanese art.

“Since I came here in 2018, I have slowly been introduced to more and more Japanese artists that I like,” he said on 1 February at the opening of Back and Forth: Paintings from London to Tokyo, an exhibition of his works held at the KEF Music Gallery in Tokyo’s Marunouchi district.

And he confessed to being particularly drawn to the works of Hokusai who, late in life, changed his name to “The old man crazy about drawing”.

Creative heritage

The grandson of the late renowned British poet, writer and broadcaster Sir John Betjeman CBE, 37-year-old Betjeman was born in New York and studied visual art and philosophy at the University of Chicago before completing a diploma in drawing at the Royal Drawing School in London, which was founded in 2000 by the Prince of Wales.

He has held solo exhibitions at Browse and Darby in London and the Identity Art Gallery in Hong Kong, and Betjeman’s works are in the collections of Prince Charles, Clare College at the University of Cambridge and the Moritz-Heyman Foundation.

Shortlisted for a number of prestigious awards, including the John Ruskin Prize and the National Art Open Competition, he arrived in Tokyo on a scholarship from Japan’s Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology to study Japanese painting.

Inspired by Japan

“I had been a painter primarily in London for 10 years, and I kind of got into a rhythm that I was quite used to,” he said. “But I don’t like getting used to things and I don’t like habit, so I wanted to inject something totally different into my practice.

“I have always been curious about Japan—particularly Japanese art and the sense of design—and it always struck me as being different to the type of thinking and the type of material practice that we do in New York and in London.

“Japanese artists, when they come to London, are always doing crazy things that nobody can understand. So, I wanted to get some of that crazy into my own work. And hopefully it has succeeded”.

Betjeman’s research is into the roots of Nihonga, the catch-all term for Japanese painting that was adopted in the late 1890s to distinguish it from Western-style works that were suddenly becoming popular. And while the works of Vincent van Gogh and other famous artists began to flood into Japan, Betjeman said, Japanese art was also going in the other direction and developing a following—particularly in Europe. In part to protect the nation’s artistic heritage, specific schools, such as Tokyo University of the Arts, were set up to encourage future generations.

Connect through art

Betjeman’s exhibition showcases the artistic exchanges between Japan and the West and is designed to encourage a dialogue between the two.

It is therefore appropriate that the exhibition was held at the KEF Music Gallery, which is a global first for a firm that produces high-end audio equipment and was founded in the UK in 1961.

Nobu Asai, president of KEF Japan Inc., which is a British Chamber of Commerce in Japan member firm, said the collaboration “reflects KEF’s long-held passion for innovation by supporting young people in creative industries”.

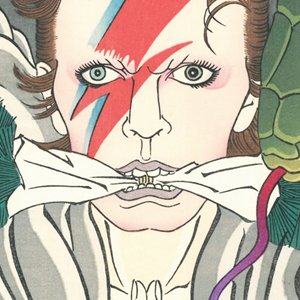

Betjeman’s exhibition features works in oils and inks, as well as pieces in the Nihonga style. Alongside a black-and-white depiction of an elderly man in a kimono are a series of studies featuring a woman in profile and more abstract pieces. Many are clearly influenced by the reduced colour palette of traditional Japanese painting and the combination of natural detail and stylised lines that are to be found in manga.

“Western oil painting and Nihonga represent distinct visual languages, which I aspire to use in combination, to approach an expression suspended between the two,” he said.

Expansion

Betjeman said he was experimenting with oils in contrast to Nihonga-style works, but expressed a profound admiration for Japanese art materials since arriving in Tokyo.

“The art materials here are amazing. They’re really expensive, but I have never experienced anything like it before,” he said. “The paper, the brushes, the pigments. Just walking into the Nihonga shops is an incredible experience. Just touching the paper or the pigments is a source of inspiration for me”.

Betjeman said he had also been strongly influenced by his father’s interest in art and the collection he amassed.

“He particularly collected works on paper—so a lot of drawings and prints—and I have always been interested in seeing an artist’s drawings, as that is the footprint or DNA of that artist. I do like looking at paintings as well, but I want to see the sketches and drawings before the paintings,” he said.

“As a youth, I was always drawing, and we had a lot of Matisse, Monet and John Piper in the house as I was growing up. I think those types of images, the etchings and the graphic collage interacting with lines had a big effect on me.

“And while it’s a bit of a cliché, part of what brought me to Japan was after seeing anime when I was about 12 years old and realising that it had such a striking contrast to American or European animation”.

Betjeman is currently applying for a two-year master’s course at his university and has a number of ambitions still to achieve, including painting on silk.