Fascinating book for foodies

First, a word about this book’s title. Umami is a Japanese word that is formed by combining the kanji for umai (delicious) and mi (taste).

It is sometimes translated into English as “a pleasant savoury taste” but, as with so many Japanese terms, this description doesn’t really quite suffice. Therefore, chefs around the world have simply adopted the Japanese word as is.

Although its existence was proposed as long ago as 1908, by Kikunae Ikeda, a professor at Tokyo Imperial University—now The University of Tokyo—the word was only officially adopted as a scientific term as recently as 1985 at the first International Symposium on Umami Taste, held in Hawaii. So what, exactly, is umami?

Today, it is widely recognised as the fifth basic taste, the other four being sweet, sour, bitter and salty.

People taste umami through receptors sensitive to glutamate, which is commonly found in the food additive monosodium glutamate (MSG). Although glutamate is itself a salt, scientists consider the taste to be distinct from saltiness.

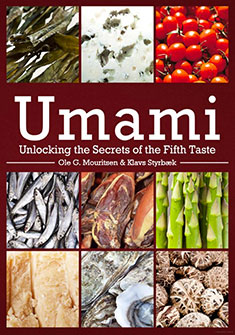

The origins of how umami was discovered are explored in fascinating detail in this beautifully presented book, which is part scientific analysis and explanation, and part recipe resource. Ikeda identified the taste when he realised that using kombu (edible kelp) to make stock resulted in a taste that was quite distinct from all others.

Researchers who followed Ikeda’s work discovered other substances that imparted umami, such as katsuobushi (dried bonito flakes) and even shiitake mushrooms. Each of these ingredients in their own right conferred this special taste for different reasons; combined, they are capable of creating dishes that today’s chefs refer to as “umami bombs”.

There is also a historical element. Glutamate has featured in the human diet for centuries.

The ancient Romans feasted on dishes dressed in fermented fish sauces known as garum. These were rich in glutamate. Byzantine and Arab cuisine made widespread use of fermented barley and, as far back as the 3rd century in China, soy sauce and fermented fish sauces, similar to the Thai nam pla condiment, saw extensive use.

Today, the umami taste crops up in some unexpected places, for example in Lea & Perrins Worcestershire Sauce, which is rich in anchovies, and even in good old down-to-earth tomato ketchup. Manufacturers of tinned soups have also realised the appeal of this fifth taste.

The authors suggest that cooking methods can also enhance the umami in dishes. They are advocates of what I suppose we must call ”slow food”—in terms of both time taken, and the movement of the same name for traditional, local food.

One recipe, for example, on page 138, calls for a mushroom essence that requires baking a batch of button mushrooms at a low temperature (80°C) for 12 hours. This is before the chef even begins to think of the other ingredients. So, perhaps this is not a cookbook for everyone.

But anyone who loves food—preparing it, cooking it, eating it—will find much satisfaction in this volume.

The photography is wonderful and the overall graphic design is excellent. It is an unexpected sort of book, and all the more desirable because of that. It is full of surprises and manages to be both informative and entertaining.

Confucius (551–479 BC) said: “Everyone eats and drinks, yet only a few appreciate the taste of food”. Here’s a book that will encourage such appreciation, along with understanding.