In her illuminating foreword to this book, Lynne Truss, author of Eats, Shoots & Leaves, recalls the occasion when she was being interviewed live on National Public Radio in the US. She was asked to comment on remarks famously made by novelist, poet and critic Sir Kingsley Amis CBE about “berks and wankers”.

In her illuminating foreword to this book, Lynne Truss, author of Eats, Shoots & Leaves, recalls the occasion when she was being interviewed live on National Public Radio in the US. She was asked to comment on remarks famously made by novelist, poet and critic Sir Kingsley Amis CBE about “berks and wankers”.

“‘Now, Lynne, would you consider yourself a berk or a wanker?’ asked the solemn broadcaster with no apparent mischief in mind”. Truss simply pressed on, “all the while praying that ‘wanker’ was either meaningless in American English or meant something innocuous such as ‘clown’”.

This is perhaps a somewhat extreme example of how linguistic differences can lead to embarrassment or worse.

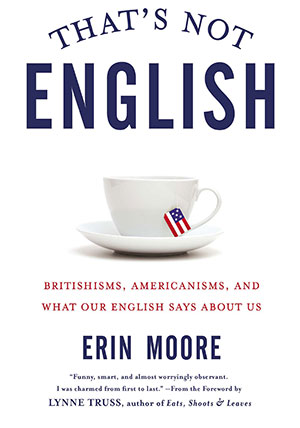

There is the old saying, attributed variously to George Bernard Shaw and Oscar Wilde, that the UK and the US are two nations divided by a common language, and reading Erin Moore’s wonderful book demonstrates just how true that is. Each chapter centres on a single word and explores the differences between British and American usage.

Take the word quite, for example. It is a word that, according to Moore, “has been the cause of confusion, unemployment, heartbreak, and hurt feelings all because of a subtle—yet vital—distinction that’s lost on Americans to the consternation of the British”.

Both nations use the word to mean completely, a usage that Moore claims dates back to around 1300 and applies when there is no question of degree. She gives the example of a bottle being “quite empty” an expression that might sound rather formal to an American but will still make sense.

The problem arises when quite is used to modify an adjective that is gradable: attractive, intelligent and so on.

“For then, the British use quite as a qualifier, whereas Americans press it into service as an emphasiser. In British English, quite means ‘rather’ or ‘fairly’ … To an American, quite means ‘very’”.

That’s Not English will appeal to those who “love language enough to argue about it; if you enjoy travel, armchair or otherwise; if you are contemplating a move to the UK or America; if you consider yourself an Anglophile; or if you’ve ever wondered why there isn’t a similarly great word for British people who love America. (Americanophile feels like a mouthful of nails, and Yankophile sounds truly disreputable.)”

The book is a true delight to read and is at times extremely funny. In the chapter headed “Pull”, Moore’s theme is dating and sex; “Cheers” is about drinking; and “Knackered” takes a look at parenthood.

The book may not be an exhaustive study of the differences between British and American English, but it is certainly extensive and there are quite a few surprises. As Moore says in her introduction, “This is a love letter to two countries that owe each other more than they would like to admit. God bless us, every one”.