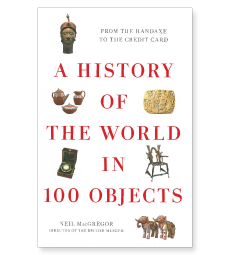

A History of the World in 100 Objects

by Neil MacGregor

Viking

£32.89

Products such as the Amazon Kindle and Apple iPad have changed the way many people enjoy the reading experience.

There is no doubt that including one of these devices in your carry-on bag when flying is better than packing numerous books, both in terms of weight and convenience.

However, sometimes a publication comes along that shouts out for a place on the bookshelf. Neil MacGregor’s magnificent A History of the World in 100 Objects is such a book.

MacGregor, the director of London’s British Museum, has a strikingly original approach to history and, in his latest offering, he includes objects that previous civilisations have left behind.

“If you want to tell the history of the world, a history that does not unduly privilege one part of humanity, you cannot do it through texts alone, because only some of the world has ever had texts, while most of the world, for most of the time, has not.

“Writing is one of humanity’s later achievements, and until fairly recently even many literate societies recorded their concerns and aspirations not only in writing, but also in things”, MacGregor said to explain what he believes is the “necessary poetry of things”.

The subtitle of the book, From the handaxe to the credit card, gives some idea to the scope of research that has gone into it.

However it doesn’t even begin to do justice to the quality of the research or the wonderful clarity with which it is set out.

Each of the 100 chapters deals with a single object and tells us much more about civilisations than most of us could ever imagine.

Each chapter is a self-contained snapshot of history in the making—or, rather, in the discovery, and there is a real sense of this on every page.

In addition, each of the 100 objects—all housed in the British Museum—is beautifully photographed and presented. There is also a very useful appendix of maps that illustrate where in the world each of the objects was found.

The original idea of telling the history of the world in 100 objects began as a programme for BBC Radio 4. Radio, obviously, does not provide visual aids and accounts, in part, for the remarkable clarity of the explanations in the book—an instant bestseller in the UK.

To write effectively for radio, you must literally paint a picture in the listeners’ heads.

MacGregor does this with superb ease and skill, and even before you reach the full-page colour plate, you can see the objects in your mind’s eye.

For example, the author described the Basse-Yutz Flagons that date back to about 450 BC and were found in north-eastern France in 1927: “They’re bronze, elegant and elaborate. They are about the size of a large bottle of wine, a magnum, and they hold about the same amount of liquid, but they’re in the shape of large jugs, with handle, lid and very pointed spout. They’ve got a broad shoulder, which tapers to a narrow, rather unstable base. But what strikes you at once about these two flagons is the extraordinary decoration at the top, where animals and birds cluster together”.

MacGregor, as an experienced curator, has considerable knowledge and this is matched by contributions from some of the most learned people in their fields: “judges and artists, Nobel Prize-winners, religious leaders, potters, sculptors and musicians”.

This is an ambitious book and succeeds splendidly on almost every level. It is an attempt to imagine and understand a world of which we have no direct experience, as the author states in his introduction.

In his opinion, the object that best defines the book is Dürer’s Rhinoceros (1515), a beast the painter drew but never saw.

“Dürer’s animal, unforgettable in its pent-up monumentality and haunting in the rigid plates of its folding skin, is a magnificent achievement by a supreme artist. It is striking, evocative and so real you almost fear it is about to escape from the page. And it is of course … wrong. But, in the end, that’s not the point”.

The 700-page book covers the period from 2,000,000 BC to 2010 AD—a breathtaking achievement, and no page is ever less than utterly fascinating.

Each of the 100 objects tells us something about what brought us to where we are today.

I wonder whether the Kindle and iPad will tell future generations about where they came from?