Academics gonged for bringing two nations closer

Two Britons have received awards from the Japanese government for their contributions over many years to improving relations between the two countries.

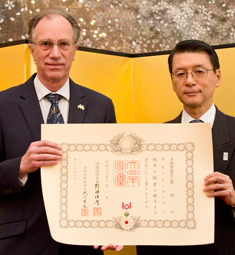

Roy Hurst OBE, a linguist who taught Russian to countless Japanese diplomats at the Defence School of Languages in Buckinghamshire, received the Order of the Rising Sun, Gold and Silver Rays, in a December ceremony at the official residence of the Japanese ambassador to London, Keiichi Hayashi.

The investiture was followed by the ambassador bestowing the Order of the Rising Sun, Gold Rays with Rosette, on Professor David Cope. Former director of the Parliamentary Office of Science and Technology, the professor took up a post at Doshisha University’s Institute for Technology, Enterprise and Competiveness in February and was recognised for promoting contacts in the field of science and technology.

Hurst, who retired in 2002 after nearly 39 years of teaching Russian, said he was “speechless” when informed of his latest honour. He was awarded Officer of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (OBE) in the 2000 New Year’s Honours list, as well as the Japanese Foreign Minister’s Commendation in 2006.

“I had the pleasure of teaching all but one of the Japanese diplomats who came to Beaconsfield”, 74-year-old Hurst said. “My first [student] was almost 50 years ago, in 1964, the last was in 2002. I didn’t get off to a particularly good start because Issei Nomura, former ambassador to Russia and former grand master chamberlain to Crown Prince Naruhito, lasted just one lesson in my grammar class since he couldn’t understand a word I was saying”.

Hurst was full of praise for the Japanese diplomats whom he instructed in the complexities of the Russian language.

“I can, with hand on heart, say that no exaggeration is needed when extolling the virtues of the Japanese diplomat students”, he said.

“They were an absolute joy to teach, and rarely, if ever, complained. They were super-intelligent, the crème de la crème; it was a rare student indeed who scored less than 90% in the first major examination at the six-month mark”.

No fewer than 15 of his former students went on to become ambassadors.

“For our part, we—both staff and UK students—were amazed at how these young men, and one lady, quickly adapted to life in Britain.

They were able to cope in class simultaneously with three of the world’s most challenging languages, without any allowance whatsoever made by the staff for the fact that they were foreigners”.

Hurst put the success of his classes down to his obvious love of the language, enormous enthusiasm, the ability to make the very difficult appear relatively simple, a desire for the students to perform to their optimum ability, constant improvements to the course, and the addition of new materials.

Cope expressed his “great honour” at being recognised with the award, adding, “I have learnt a great deal over the 30 years since I first came to Japan—and am pleased to have contributed, in a small way, to good relations between our two countries”.

A life member of Clare Hall, Cambridge University’s special international postgraduate college, 66-year-old Cope first came to Japan in 1983 to study the country’s policy on local air and water pollution control, which was recognised even then as the best in the world.

While the expertise he has shared has primarily been in the areas of physics, energy and the environment, Cope has been deeply involved in links between Britain’s Parliament and Japan’s national Diet in electoral reform and the operation of coalition politics.

In addition, he is a trustee of the Great Britain Sasakawa Foundation, which provides grants to promote bilateral relations in everything from medical research to a forthcoming conference on politeness.

As a visiting professor for one year at Kyoto’s Doshisha University in 1997, Cope travelled the length and breadth of Japan and indulged his passion for the country’s coastal environment.

Just as memorable, although in a very different way, were his experiences in Kobe, shortly after the 1995 Great Hanshin Earthquake, and in Tokyo during the Great East Japan Earthquake, when the quake struck.

The professor visited Minamisanriku and Kessenuma in Miyagi Prefecture, Rikuzentakata in Iwate Prefecture, as well as other cities affected by the disaster, and participated in various activities in the UK to provide support and assistance for victims of the triple disaster.

“The things I saw [in the disaster areas] are seared on my mind for as long as I live”, Cope said.

However, he is immensely optimistic about future ties between Japan and the UK.

“The relationship [between the two countries] has blossomed enormously”, he said. “Before it was dominated by Japan ‘specialists’, particularly on the cultural and historical sides; now there is much more contact across a wide range of areas.

“Of course, there is a worry that Japan is being eclipsed by the rise of China in public awareness, so it is good to know that numbers are increasing [of students] signing up to study Japan-related subjects at UK universities”.