Interview with Lord Tony Hall, chief executive of the Royal Opera House in London

In times of financial strain, the arts are often among the first victims of government funding cuts. But the austerity measures being implemented in Britain and elsewhere should not deter those responsible for promoting culture from reaching out to new audiences, said Lord Tony Hall, chief executive of the Royal Opera House in London.

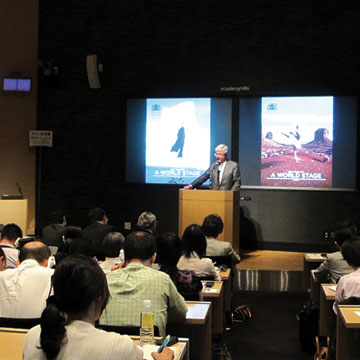

A vibrant arts scene is essential to the cultural fabric of a civilised society, Hall told a British Council seminar on investing in the arts during a recent visit to Tokyo.

“In any creative organisation there needs to be the ability to invent, to try new things, to take risks, which to an outsider might look like chaos,” said Hall, who became a life peer earlier this year. “Managing this is, to put it mildly, difficult. If you get it wrong, you can end up with the reputation that we had at the Royal Opera House in the late 1990s, when we lost legitimacy. Most people failed to see the point of us.

“But if you get it right, then your creative teams can provide and produce art of the very highest quality”.

Since becoming chief executive in 2001, Hall has attempted to retain the opera house’s artistic credentials while reaching out to new audiences in Britain and beyond. He was behind the installation of outdoor screens relaying performances to crowds in London’s Trafalgar Square and, more controversially, introducing discount-price opera tickets for people including readers of the Sun, a tabloid newspaper not usually associated with enthusiasm for high culture. Inevitably this and other initiatives — notably a forthcoming opera about the actress and glamour model Anna Nicole Smith, who died in 2007— have invited accusations of “dumbing down”.

Hall disagrees: “There will be people who say, ‘What is the Royal Opera House doing commissioning an opera about Anna Nicole?’ But we all feel that a statement is being made about her, the celebrity lifestyle, her 15 minutes of fame and demonstrating that this is a proper subject for opera”.

The challenge of maintaining a properly funded arts scene in the midst of widespread belt-tightening is not confined to the UK.

Hall’s Japanese counterparts complained that it was becoming increasingly difficult to get work commissioned, and that outmoded labour practices were inhibiting their ability to pursue the unapologetic commercialism Hall has used to good effect in Britain.

But Hall insisted that cash had to come from multiple sources, while maintaining the central role of the Arts Council, a government-supported body that funds the arts in England, Scotland and Wales. The idea that the arts are “government-grant junkies” is outmoded, he said. Additional money now comes from the private sector, ticket and merchandise sales, the Royal Opera House’s shop and restaurant and, increasingly, from donations.

British Council

He dismissed the caricature of arts management as “un-businesslike, rather unprofessional and run by a bunch of luvvies”—an unkind reference to the touchy-feely arts intelligentsia of popular, and often media, imagination.

“That, in my experience, is not true. I see a very dedicated cadre of men and women taking risks, managing the chaos of creativity. In other words, I see creative entrepreneurs. And one of the reasons for arts in the UK doing so well is the combination of outstanding artists and creative entrepreneurship”.

The figures support his claim: the top eight tourist attractions in the UK are national museums or galleries; heritage and the arts are cited by eight out of 10 tourists as the reason they visit Britain.

The thirst for culture in Britain is “an impressive achievement as we come out of a recession”, Hall said. “And I believe it shows that we all need and appreciate what arts and culture can give us, even more when times are tough than when times are good”.

He described as “dead” the familiar elitism versus access debate, centreing on performing arts such as ballet and opera.

“What we aim to do is unasha-medly elitist in one way—we want to attract the very best artists to come and work at the Royal Opera House. We’ve got to be world class. But it’s not just about getting the very best; it’s about opening access to the very best to the many”.

Hall tackled the perceived exclu-sivity of his company’s productions by introducing ticket discounts and issuing special invitations to groups of people who would never have dreamed of going to the opera or ballet. “For me, those are some of the most moving events we’ve had”.

Japanese arts promoters voiced frustration at the struggle to convince public bodies to fund new projects. But if Japanese interest in the Royal Opera, which includes the Royal Ballet, is any indication, the public thirst for these “rarefied” art forms remains unquenched.

Hall’s visit coincided with a tour to Japan that included, for the first time in the country, performances by both companies, and the first in 18 years by the Royal Opera.

The highlight was a valedictory performance by Miyako Yoshida, a Japanese dancer with Royal Ballet companies for 25 years, who ended her career dancing the role of Juliet, in “Romeo and Juliet”, at Tokyo Bunka Kaikan on 29 June.

“Seeing the enthusiasm of audiences for every performance of the Royal Ballet and the Royal Opera … I find that really impressive”, Hall told BCCJ ACUMEN after the seminar.

“I don’t think we in Britain understand just how many things we have got right. We’ve got a funding model that works. It’s going to come under a huge amount of stress from public spending cuts, but it works.

“I don’t have to go to the Arts Council and beg to fund specific productions. It is a case of the government, through the Arts Council, trusting the people who are running our big and small arts institutions to get on with the job. That’s a very mature relationship … and I’m overwhelmed that the Japanese want to learn from us”.

Japan will be central to the Royal Opera House’s attempts to broaden its global appeal in the coming years, and Hall was appropriately effusive in his praise for Japanese audiences: “After the UK, Japan is a really important market for us, because here we see people who are passionate about opera and ballet.

“The performers love coming here. They feel very much at home”.