By Richard Lloyd Parry

By Richard Lloyd Parry

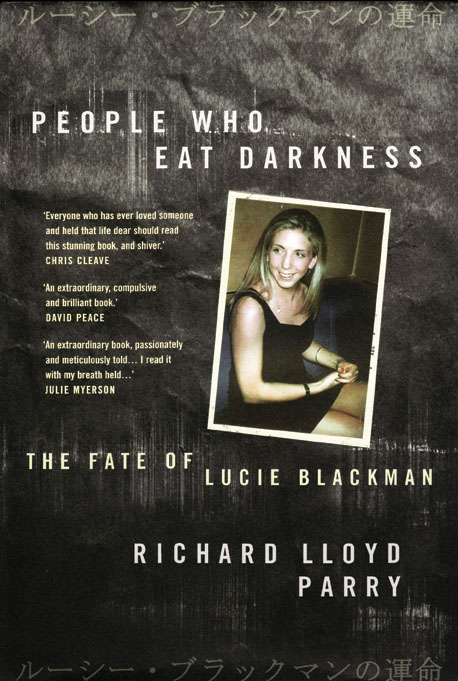

“Lucie Blackman died … before I ever knew that such a person existed. In fact, it was only because she was dead or missing … that I took an interest in her at all”, admits Richard Lloyd Parry at the beginning of his 404-page, non-fiction account of the 21-year-old murder victim and the enigmatic man accused, but not convicted, of killing her.

Blackman, who had been working as a hostess in a Roppongi nightclub, was last heard from on 1 July, 2000, via telephone. Just two days later, her friend Louise Phillips filed a missing person’s report at the Azabu police station and, soon after, with the British Embassy Tokyo. These efforts were followed by a barrage of calls from Blackman’s increasingly frantic family. Eventually, pressure was exerted via diplomatic channels, spurring the initially reluctant police to launch a nationwide manhunt.

But it was not until the following February that police discovered Blackman’s dismembered corpse, buried beneath a seaside cliff in Zushi City. By then, the key suspect in her disappearance—a secretive 48-year-old businessman named Joji Obara—was already in custody. Although police searches turned up a wealth of circumstantial evidence—including a supply of date rape drugs (that may have sedative, hypnotic, dissociative, and/or amnesiac effects) and reportedly hundreds of videos showing him having sex with women who appeared unconscious—Obara denied involvement in her death, and continues to deny it 10 years later. (Despite claims of innocence, Obara, who was sentenced to life imprisonment after being found guilty of a separate homicide, arranged to pay a hefty solatium to Blackman’s family.)

Parry’s account pulls no punches, and the tragedies that unfolded notwithstanding, he is not beyond supplementing his account with occasional wry insights on Japan’s “water trade”—the traditional euphemism for Japan’s night-time entertainment business provided by hostess bars, bars and cabarets. Thus, on page 68, he writes: “No other race has expended the imagination and creativity that the Japanese have put into the packaging of paid sex. In order to veil the obvious, sex businesses package their services under a bewildering range of names, so numerous and fast-changing that it is a struggle for the non-specialist to keep track”.

Once readers’ curiosity turns from Tokyo nightlife to details of the crime itself, they are likely to be struck by the extreme contrast between the vivacious former British Airways stewardess and her accused killer. Joji Obara, a naturalised Japanese who was born in 1952 in Osaka as Korean national Kim Sung Jong, had inherited considerable wealth, which he’d parlayed into an even larger fortune during the bubble economy of the 1980s. He drove expensive foreign cars, lived in a home that was palatial, even by the standards of the affluent neighbourhood of Denenchofu, and spoke good English. What little is known about Obara’s early youth must be gleaned from corporate records, a very few old and blurry photos, and the vague recollections of his Japanese schoolmates.

In addition to shifting between residences and going by an assortment of aliases, Obara had also procured a supply of untraceable cell phones just before new regulations requiring owner registration went into effect, stymieing investigative efforts. Thus prepared, Obara flitted through the Roppongi twilight like a shape-shifter, concealing his identity more like an intelligence operative in a Frederick Forsythe thriller than a garden-variety serial rapist.

While Parry explains Obara’s background as a member of Japan’s Korean minority, he could find nothing concrete to link the man’s ethnicity to the hows and wherefores of his extreme behaviour. And because neither the prosecution nor the defence sought to introduce testimony by a criminal psychiatrist at Obara’s trial, the man is likely to remain an enigma. People Who Eat Darkness is a meticulously researched and harrowing account of the events of the summer of 2000, with no happy ending.