In March 2011, with Japan already reeling from The Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami, a further disaster was brewing in the Tohoku region. With the tsunami taking emergency generators offline, the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant soon witnessed three nuclear meltdowns, the worst nuclear disaster since that at Chernobyl in 1986.

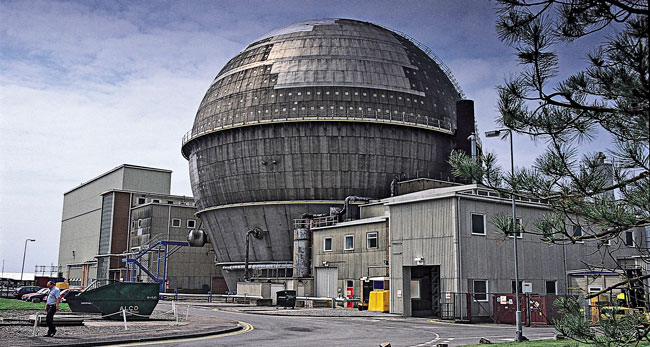

While Japan and the rest of the world watched with horror the unfolding disaster at the plant, there were people in the UK who believed they had knowledge and experience that could help Japan in its hour of need. That was thanks to ongoing work at Sellafield, a major nuclear site in Cumbria, parts of which were used in the development of nuclear power in the early days of the nuclear industry during 1940s, ‘50s and ‘60s and are now being decommissioned.

Facilities dating back to the 1950s are being decommissioned at Sellafield.

This sharing of knowledge in the aftermath of March 2011 eventually evolved into a partnership—between Sellafield Ltd. and Tokyo Electric Power Company Holdings Inc. (TEPCO)—which continues to this day.

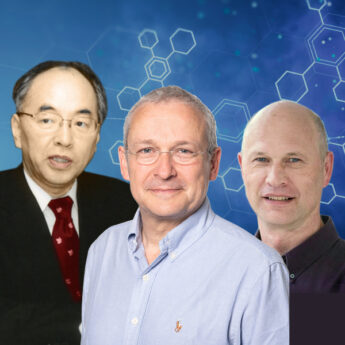

Speaking at a 16 January British Chamber of Commerce in Japan event, held in association with the Department for International Trade, at the Shangri-la Hotel in the Marunouchi district of Tokyo, some of those involved in the partnership discussed their work and the value of this UK–Japan collaboration. On the panel were Roger Cowton, head of external affairs at Sellafield Ltd., Masayuki Yamamoto, group manager of Nuclear International Relations and Strategy Group at TEPCO, and Keith Franklin, who is first secretary, nuclear at the British Embassy Tokyo.

Although the seeds of the partnership were sown in the summer of 2011 after Franklin arrived in Japan on secondment from the National Nuclear Laboratory, it only really began in earnest in 2012, after a team from TEPCO visited the Sellafield site.

“The guys from TEPCO realised the similarities in the decommissioning process”, said Franklin. “The collaboration started in practice then, which we subsequently formalised in an agreement”.

Although ostensibly very different—one plant’s situation is attributable to a major natural disaster, while the other’s isn’t—the plants, nonetheless, have much in common. The similarities range from geography (both share coastal locations) to the nature of the radioactive material on site.

Both are also what would be termed “dirty” sites—that is, sites where the facilities weren’t turned off at the end of their lifecycle and then dismantled. As a result, the situation in some buildings is not properly understood and there are plenty of “unknown unknowns”. How to handle these challenges is now a key aspect of the partnership, with both sides sharing their experience in this area.

“Due to the legacy, inherited from the beginnings of the nuclear industry, Sellafield has got some nasty, highly radioactive material in facilities from which it needs to be retrieved and stored safely. Due to the accident at Fukushima Daiichi, TEPCO find themselves with similar challenges”, said Franklin.

“It’s happened for a different reason, but when you boil it down to the technical challenges, those technical challenges are very similar. And those technical challenges actually stretch into how you manage and organise yourself in order to deal with such a situation, as well as the practicalities of the chemistry and physics of it”.

Taking it further

Franklin identified two areas that are rich in scope for further collaboration. The first is in the area of site management.

“Sellafield is moving from reprocessing to decommissioning over a long period of time; Fukushima moved overnight”, he said. “How you manage an operational site versus how you manage a decommissioning site are very different”.

The other aspect highlighted by Franklin was the use of technology, and in this area the fact that Sellafield is further ahead in its decommissioning and has been doing it for longer has strong benefits for Fukushima.

The Sellafield site is expected to be cleared by 2120.

“Already there’s one or two examples of companies who set up in Cumbria to deliver their specific technologies to Sellafield and found that somewhere else in the world needs the same technology, and that’s at Fukushima Daiichi”.

This technological progress also plays into the timescales involved in the Sellafield project. At the moment, it is expected to be finished in 2120, although Cowton cautioned that this estimate would almost certainly be wrong. In part, that could be because innovation in Japan could help speed up parts of the process.

“We constantly review that longer term plan because we want to make sure that we are leveraging the benefits that we can find from the various technical solutions”, he said. “Some of the work that TEPCO are doing at the moment, some of the robotics work that has been developed through the various arrangements that are here in Japan, will inevitably give us … something that will help us to do something different at Sellafield”.

Cowton added that engaging stakeholders and the local community was another area where the partnership can develop further.

“We’re also looking at the way in which TEPCO is working with its key stakeholders, the communities around the Fukushima Daiichi site, the wider relationships with government and other organisations”, he explained. “Sellafield has been doing these sorts of things for many years, and that’s a real area where we can grow and develop together, I think, because you can never do enough work in that area”.

This has seen Yoshiyuki Ishizaki, representative of the Fukushima Revitalization Headquarters, give an update on progress to Sellafield and also witness their engagement with various stakeholders.

“I know some of those things that have been picked up from the UK are going to be adopted in a Japanese way, but utilised over here”, said Cowton.

Personal connections have played an important role, too. After joking that he had eaten some very strange Japanese food as part of the team building process, Cowton praised the strength of the personal relationships in the partnership.

“We have a very good personal connection—we can say things to each other quite frankly, quite straightforwardly, quite openly, and I think that’s really important.

“My first experience of coming to Japan [in 2009, for unrelated work] … I was terrified of offending anybody, getting it wrong, all that sort of thing. The relationship is now much more what I would describe as a Western relationship—it’s very easy to be very honest, very direct, very forthright.

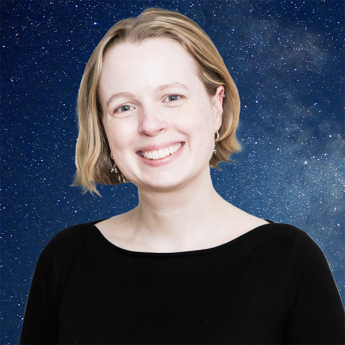

The International Atomic Energy Agency inspects decommissioning at Fukushima Daiichi.

“I think that’s essential as we try to both share, and develop and improve what we’re trying to do. That’s come from the fact that the two of us have worked together on this for over two years now—we’ve met each other face to face 10 or 12 times across that period, every month we meet through a video conference and discuss progress”.

Although the earthquake, tsunami and nuclear incident caused massive amounts of damage and challenges with which Japan is still wrestling, the Sellafield–TEPCO partnership gives hope for the future.

“Back in March 2011, everything suddenly changed”, said Yamamoto, noting that this led people to reconsider the way they worked. “[The partnership is] a great opportunity for our people to grow, to have the capability to do something different compared with our past practices”.