This is the season in Japan when the quest for the word of the year begins in earnest. No doubt some rugby terms will find their way onto the shortlist this year. Maybe even Brexit.

This is the season in Japan when the quest for the word of the year begins in earnest. No doubt some rugby terms will find their way onto the shortlist this year. Maybe even Brexit.

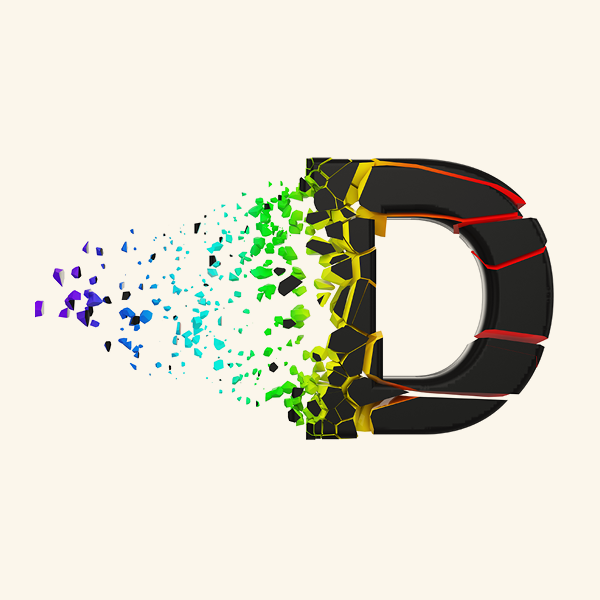

For myself, I feel that the first place ought to be awarded to the letter D. I know that D is not a word, but never mind. The letter has been quite ubiquitous throughout the year, in ways that seem to symbolise very well what kind of year this has been.

Falling apart

In reflection of the kind of things that have been going on around the world, three words beginning with D most especially have stood out:

- Deglobalisation

- Decoupling

- Disintegration

To my mind, these three D-words represent the happenings of 2019. Deglobalisation entered the global lexicon around the beginning of this year. Up to a point, people seemed to accept quite unquestioningly that globalisation was a river of no return. But now, everyone talks and writes about deglobalisation as though it had become an unavoidable fate of the human race. What with all the cries of “my country first” cropping up everywhere and unilateralism running rampant, the loss of conviction in one-way globalisation does not really come as a surprise.

It is a worrying development, nonetheless. There is bad globalisation and good globalisation. Bad globalisation leads to exploitation of the weak and the small. Good globalisation leads to inclusiveness, sharing and caring across borders. For people to turn their backs on the latter—as if there was no alternative—would be an altogether sad and foolish thing for the human race.

Decoupling is the talk of the town concerning the US and China. At one point, the pair were being talked about as “Chimerica,” because their two economies had become so intensely linked through supply chains and market access. But now, that relationship is in peril. Although trade tensions seem to be abating somewhat, techno-wars and export bans are still wedging Chimerica apart. A clean or rather messy break is still very much on the cards.

Disunited Kingdom

The other decoupling that we are focused on is, of course, Brexit. Never has the world seen a more baffling divorce process. How much uglier and sillier will the process become? Will it somehow manage to end up becoming an amicable one? Will the divorce actually happen at all?

Turning to the third D-word—disintegration—the question about Brexit, if and when it happens, is whether it will bring about the disintegration of the United Kingdom as we know it. Will Northern Ireland decide to leave the UK and become part of the Republic of Ireland? Will Scotland hold another referendum and walk away from Great Britain? What would Wales do in that eventuality?

Another internal disintegration threat seems to be rearing its sinister head in Germany, even as the country in November celebrates the 30th anniversary of the coming down of the Berlin Wall. Disillusioned East Germans claim they are still being treated as second-class citizens. They are starting to question the value of democracy. They have become doubtful of the power of liberal societies to deliver the security and happiness that they seek. “It wasn’t supposed to be like this” seems to be the sentiment that many in the five East German states are sharing. As a result, they are increasingly voting for the ultra-right Alternative for Germany party in local elections. German reunification was a miracle come true. It is so much to be hoped that a counter-miracle in the form of German disintegration does not come about.

Internal disintegration is arguably a more realistic possibility in Spain, where separatist Catalans are seeking the opportunity of another referendum on independence. And in Italy, a north–south break is an ever-rumbling leitmotif.

It should be noted that even Japan is not totally immune to the potential of internal rupture. The Tohoku region, comprising prefectures to the north-east of Tokyo on the Japanese mainland, found themselves on the wrong side of the civil war that led to the creation of the Meiji government. With considerable good reason, they felt cheated and tricked into becoming the rebels standing in the way of progress.

The sentiment lives to this day. The people of Fukushima and elsewhere in the Tohoku region openly expressed displeasure with the lavish celebration of the 150th anniversary of the Meiji Restoration put on last year by the government of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe. For them, the days leading up to 1868 were a time of bloodshed and tragedy. There is nothing for them to celebrate in that piece of history. It does not help at all that Abe’s constituency exists in the prefecture of Yamaguchi, which played a central part in the creation of the Meiji political regime.

And Okinawans watch with keen interest how the Catalan independence movement is playing out. Should internal disintegration start to look like a worldwide phenomenon, might it serve to activate Japan’s own lines of division within?