If nothing else, the world’s ongoing fight against the coronavirus pandemic underscores the importance of international medical collaboration.

On 11 May, Japan Society chairman Bill Emmott was joined by Professors Paul Riley and Georg Holländer from the new Institute of Developmental and Regenerative Medicine (IDRM) at the University of Oxford and Professor Shin’ichi Takeda of the National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry in Tokyo to discuss regenerative medicine and its potential impact on global health.

Opening doors

Professor Paul Riley

Riley started the event by explaining what regenerative medicine is.

“Regenerative medicine is the process of replacing or regenerating human cells, tissues or organs to restore or establish normal function. And I think it’s fair to say that regenerative medicine is extremely challenging. There have been very few clinical successes in this space, which means that it’s very important to think about alternative ways to tackle potential degenerative diseases”.

Riley went on to explain the ongoing IDRM project within the Medical Sciences Division at the University of Oxford. Led by himself and Professors Georg Holländer and Matthew Wood, the latter of whom could not join the webinar, the project will be opening its doors in January 2022.

“It is, at its core, a merger of developmental biology and regenerative medicine, and our philosophy is very simple: we seek to understand how tissues and organs are formed in during development during pregnancy, to then inform strategies to repair and replace the same tissues and organs when damaged or injured through disease”.

The IDRM is a three-storey building which will have themes in immunology, cardiology, and neurology.

“Integrating across those, 50 percent capacity will be from incoming Oxford researchers. But also it represents a very valuable recruitment tool and, of course, a tool in which we hope to establish international links and further collaborations particularly with our colleagues in Japan”, Riley said.

Future goals

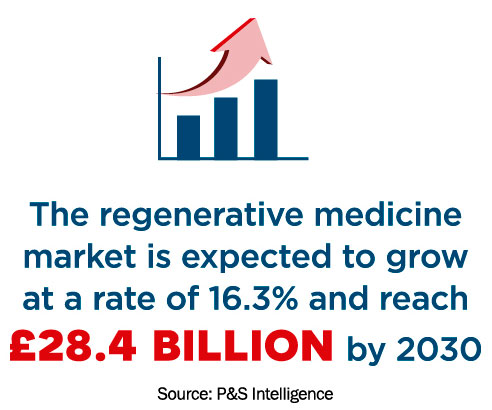

Riley explained that two thirds of the deaths worldwide are due to non-communicable diseases (preventable diseases through lifestyle modification). Many deaths are caused by non-viral type diseases, and a lot of these are cardiovascular, neurological or immune system disorders that have a developmental origin. Hence, there is an urgent need for new drugs and therapeutic strategies to replace and restore damaged tissue arising from birth defects, or acquired adult tissue injury and disease”, Riley explained.

It was said that the goals of the institute are to improve the current understanding of the molecular and cellular inputs to control the normal development of the heart, brain and immune system, in an attempt to decipher mechanisms that cause congenital disease, birth defects and an increased susceptibility for adult disease.

Riley explained the importance of integrating world leading research programs. The hope is that this will inevitably lead to therapeutic endpoints in treating patients.

“None of this can be done locally and without international collaboration. We are extremely proud of the fact that we’ve got significant collaborations with Japanese colleagues. And we’d like to establish those much further particularly thinking about the exchange of trainees, so students and postdocs, and establishing fellowship programs, to enable those trainees to experience the best of what we have to offer in Oxford and elsewhere in host Japanese institutions”, he said.

Immunology

Professor Georg Holländer

Holländer explained why studying the immune system is of importance, particularly in the current pandemic. He explained the immune system’s ability is to discriminate between self (the body’s own normal cells) and nonself (abnormal cells). “When recognising self, the immune system should be tolerant. In the other instance, where it recognises non self, it should create a directed and effective immune response.

“So what the immune system does is similar to what our cognitive system does, it recognises patterns established as normal… and the nonself. On the one hand, we have the innate immune system, which responds very quickly but can only recognise a number of different foreign antigens or normal self antigens. On the other hand, we have the adaptive immune system, which takes a couple of days to respond, but has a non-limited capacity to recognise nonself, but also actively prevents its activation when recognising self. This results in neurological memory”.

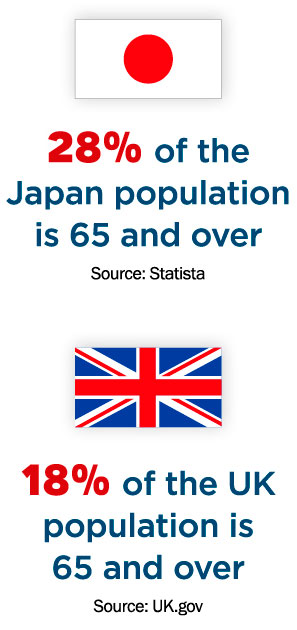

At the centre of the adaptive immune system are T cells, explained Holländer. “These cells are generated in the thymus, which is an organ sitting on top of the mount in the chest and produces new T cells that orchestrate the adaptive immune response. However, this organ decreases in size and function with age. So, when you are older than your mid-teens—namely, after puberty—the final output decreases dramatically. It is merely a trickle at ages beyond 50.

At the centre of the adaptive immune system are T cells, explained Holländer. “These cells are generated in the thymus, which is an organ sitting on top of the mount in the chest and produces new T cells that orchestrate the adaptive immune response. However, this organ decreases in size and function with age. So, when you are older than your mid-teens—namely, after puberty—the final output decreases dramatically. It is merely a trickle at ages beyond 50.

Holländer explained that this is important because we only have a limited number of T cells in our body, and only a relatively limited number of their receptor specificities recognise all different antigens. “We need to keep that pool of T cells alive because, with age, we decrease our vaccine responses. We are more impaired in our responses against infectious diseases, or malignant cells in the context of cancer and the chances of developing autoimmunity increases”, he explained.

Trying to better understanding how the thymus can be regenerated is the focus of the work in the immunology branch of the IDRM. “This is an effort that is not only to be exercised in idea, but is actually a global activity with a lot of colleagues and friends in Japan, who contribute to our growing understanding of thymus epithelial cells, what their stem cells look like, how we can mature them, manipulate them, how they grow. And last but not least, how well their function is to teach the immune system to distinguish between self and nonself”.

Holländer explained that these collaborations are with universities in Kyoto, Sendai, Takashima and Tokyo. “This is also an activity we have been able to undertake in collaboration with Dr Tetsuya Nakamura, Chief Director of Itabashi Medical System Group (IMS-Group), who enabled us to create the institute, and with whom we plan to establish exchange fellowship roles between our organisations to further our knowledge in regenerative medicine”.

Tokyo input

Professor Shin’ichi Takeda

Takeda, of the National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry, explained that he has been participating in the progress of stem cell research, particularly in the areas of skeletal muscle and muscular dystrophy. He noted progress and research based on genetically corrected cells, gene therapy, and many others.

“The key player in muscle regeneration is subtle cells. There are progenitor cells that support the muscle regeneration process together with macrophage cells. These cells also play a distinct role in the step of fibrosis and fatty infiltrations in skeletal muscle as well”, he said.

Speaking on the research groups within the neuroscience department of the IDRM, he noted the importance of collaboration, “There is a long history of collaboration between the National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry and the University of Oxford. We are now expecting the results of the current ongoing collaboration, and also future extended collaboration programmes”.