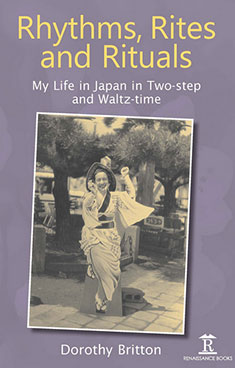

Dorothy Britton, Lady Bouchier MBE, led a highly unusual life. Born in Yokohama, she was educated first in Japan and subsequently in the UK and the US before returning to Japan after World War II, largely remaining here until her demise in February.

Dorothy Britton, Lady Bouchier MBE, led a highly unusual life. Born in Yokohama, she was educated first in Japan and subsequently in the UK and the US before returning to Japan after World War II, largely remaining here until her demise in February.

This memoir is the story of that extraordinary life told in her words.

To those who knew Britton, it will have the ring of authenticity in the sense that this is her voice; this is the language she used in everyday conversation. To others it may appear to come across as slightly Edwardian and “dear diary-ish”.

But the author has much to recount, from her experience of the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923 (her description of how it ravished Yokohama is gripping) to her studies with composer Darius Milhaud (like much in Britton’s life, luck—and connections—appear to have played a huge part).

Britton, who was bilingual—if not, indeed, trilingual, for she spoke French as well—had firm views as to how foreign languages ought to be taught. In particular, she also expressed some interesting, if unorthodox, views on how English should be taught to Japanese.

She speaks of the “katakana prison”; in other words the way the use of katakana inhibits the Japanese learner of English in sounding English.

No doubt her ear for music—she was an accomplished musician and composer in her own right—encouraged her in the belief that how we hear sounds greatly influences the way we reproduce them and, by extension, how we understand them. After all, this is the way, as babies, we learn our native tongues.

Britton is wonderfully frank about her innocence when it comes to love and sex, and equally frank when she comes to revealing how she learned about homosexuality.

I find it curious that she insists on referring to “gaye” people. I am unsure about that final “e”. Perhaps it is because she did not want to lose the Edwardian sense of gay being carefree or bright.

Her account of meeting the man who would become her husband, Sir Cecil “Boy” Bouchier KBE CB DFC is honest and revealing, as is her account of her relationship with her stepson Derek, to whom she remained loyal and supportive, despite his disability.

This is clearly a book that has been self-published—there are credits to the Great Britain Sasakawa Foundation and the prestigious Tokyo Club, established in 1884, for making publication possible.

While celebrating the personal recounting of her extraordinary life, it is impossible not to think that the book might have been far better served if there had been a keener editorial eye on timelines and continuity.

Nevertheless, this is an entertaining volume that will be of great pleasure to her many friends and, perhaps, an eye-opener for blue-eyed newbies to Japan.