Science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) education is a prominent focus in today’s schools. And while young girls tend to do well in these subjects, many do not pursue STEM studies when they move on to higher education. As a result, women remain under-represented in executive positions in STEM fields.

Science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) education is a prominent focus in today’s schools. And while young girls tend to do well in these subjects, many do not pursue STEM studies when they move on to higher education. As a result, women remain under-represented in executive positions in STEM fields.

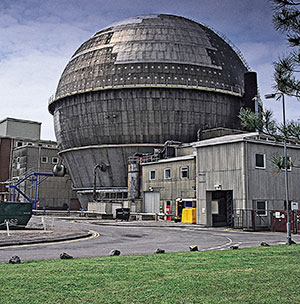

To advance understanding of, and participation in, STEM education, the Paris-based Nuclear Energy Agency, part of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), held an event entitled Joshikai II for Future Scientists: International Mentoring Workshop in Science and Engineering. The workshop was conducted on 8 August at Tokyo’s Miraikan—The National Museum of Emerging Science and Innovation.

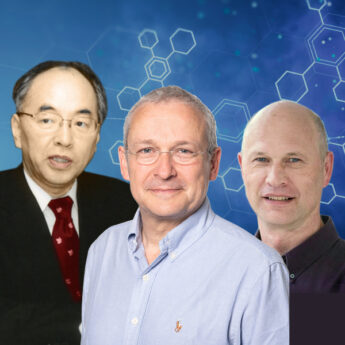

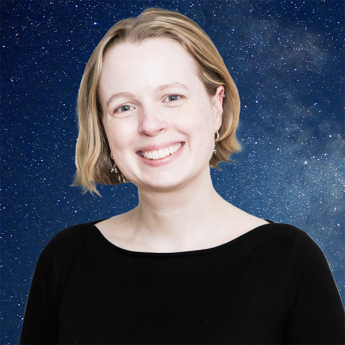

The occasion was an opportunity for a large group of female students to engage with highly accomplished female scientists and engineers, including Cait MacPhee CBE, a professor of biological physics at the University of Edinburgh, who gave a speech about her education and career.

After finishing secondary school, MacPhee worked as a lab technician before going on to study music at university. After realising that music was not for her, she decided to pursue a Bachelor of Science at the University of Melbourne in Australia, where she majored in biochemistry and immunology. She completed that degree in 1995 and, four years later, received a PhD from the university’s Faculty of Medicine.

A chance encounter with a notable scientist resulted in MacPhee being offered work in the University of Oxford’s chemistry department, where she stayed from 1999 to 2001. This propelled her on to the University of Cambridge Cavendish Laboratory, one of the most famous physics departments in the world. She worked in Cambridge from 2001 to 2005.

In 2006, MacPhee joined the University of Edinburgh and was promoted in 2011 to the post of Professor of Biological Physics—a position she still holds. “The University is over 400 years old”, she explained. “I was the first female physics professor they had ever appointed”.

Encouraging future female scientists is important to MacPhee, and her work to introduce primary-school girls to science resulted in a Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the Great British Empire (CBE) honour being bestowed on her in 2016.

After outlining this career path in a keynote speech—and insisting that the students in attendance pursue whatever careers they want—MacPhee sat down with BCCJ ACUMEN to talk about the reason she feels that encouraging children in the early years is key to shaping the future of inclusivity in science.

How important are events such as this?

I think they can make a critical difference to individuals, I really do. We may only influence the choices of one or two people in the room, but—if we do—I think that is a success. If one person stands up and inspires you, that can make a complete difference in what you decide to do. I think events like this, that highlight women who have gone through this career path, enjoy it and clearly love their job, are very valuable.

Has being a woman impacted your career?

It’s very difficult to avoid noticing when you are one of 20% in the room. It’s very difficult to avoid noticing when you go to a meeting and you are the one woman in the room. I have also spoken to male colleagues who have gone into fields that are female dominated, and they commented that, if you are the only man in the room, that naturally feels quite intimidating. It’s not a sense of hostility, it’s just a sense of “there are no people like me”. I don’t feel that I was treated any differently. If I was going to be treated differently, I walked away from those opportunities because I didn’t think they were the right ones for me.

Why are women under-represented?

The statistics are different in Japan. But if you look at Europe, for example, in fields such as biological sciences, women are not under-represented. If you look at university-level chemistry, women are typically not under-represented. In physics, the numbers have stubbornly been about 20% for the past 30 years; and everything we have done hasn’t shifted that number. Why do I think that happens? There is a notion that some subjects are for boys. Maybe it is the way we phrase things in secondary-school textbooks. It is possibly the toys that people play with, building things. It could be playing with things such as Lego, which leads to being manually dexterous and going into engineering disciplines. I think it is very, very complicated. Some people seem to have passed through that without even noticing.

One thing I do want to say, though, is that this distinction happens at a very young age. It can be entrenched before kids get to secondary school, so I think we have to work with children and show them the enjoyment of doing science very early on. I think you want to try and encourage them and enthuse them. This kind of centre, Miraikan, is absolutely fantastic and is designed to engage quite-young children and their families. I think that is exactly the type of initiative we need.

How did it feel being awarded a CBE?

It gives recognition to the importance of doing this, of engaging girls while they are young and of realising that we are missing out on the potential of a proportion of the population because they are not necessarily engaging with the subject. Also, that we could do a lot more if we had the complete diversity of viewpoints represented. It reflects that this is a very important argument to make. So, from that point of view, I think it’s a very nice thing.

Do you have advice for those interested in your field?

If you don’t definitely know what you want to do, don’t feel that means you shouldn’t go in to this field. It just means you haven’t found the right place yet. People must explore to discover the area that is most suited to them. Have confidence in yourself and, if you don’t know everything now, have faith in the fact that you can eventually learn it. Not everyone knows everything immediately. If opportunities come up, have the confidence to take them.