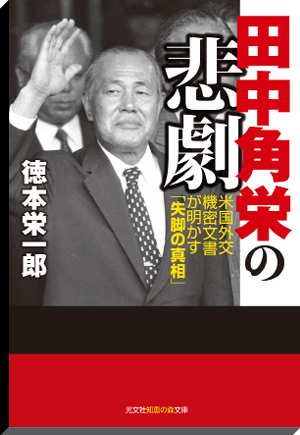

By Eiichiro Tokumoto, former Reuters correspondent, author, and investigative journalist.

My book tells the story of Kakuei Tanaka, the most popular and controversial politician in post-war Japan. Tanaka, born into an impoverished farm family in rural Niigata Prefecture, never progressed beyond elementary school. But, through backbreaking toil and a combination of extraordinary energy and charm, he climbed to the pinnacle of power, becoming prime minister of Japan.

Tanaka was also singled out as the “personification of money politics”; he was forced to resign after his questionable fundraising deals were exposed. Then, in February 1976, a US Senate committee exposed what was to become known as the Lockheed Scandal, and he was arrested on the charge of having accepted ¥500 million in bribes from Lockheed Aircraft Corporation.

Based on numerous declassified documents in the United States and Great Britain, as well as extensive interviews with Tanaka’s friends and foes, I have shed a harsh new light on the drama of Tanaka’s rise to power and spectacular fall from grace. One of the key players during his tenure was an enigmatic fixer who served as an informal adviser to the prime minister’s natural-resource diplomacy, and as a mediator between the British oil major, then named the British Petroleum Company, and Japan.

In October 1973, Tanaka had visited London for a meeting with British Prime Minister Edward Heath. On the agenda was Japanese participation in the North Sea oil project.

High demand

The decades of Japan’s high-economic growth in the 1950s and the 1960s triggered a surge in the demand for oil, and the country was trying to diversify its sources. Tanaka proposed that, in return for financial involvement in the North Sea, Japan would take supplies from BP’s other oil fields.

Three months prior to the summit meeting, on 5 July, 1973, a Japanese businessman in his late sixties had visited the British Embassy Tokyo near the Imperial Palace to meet British Ambassador to Japan Frederick A. Warner. The man’s name was Seigen Tanaka. He was president of International Energy Consultants and a right-wing fixer, nicknamed the “Tiger of Tokyo”, and his inquisitive gaze evoked the image of a samurai.

According to British Foreign & Commonwealth Office (FCO) documents, Seigen proposed the ambassador to launch a discussion forum which would enable both sides to adjust their energy policies.

Following discussions with BP management in London, Seigen also raised the possibility of Japanese participation in the North Sea project and added that he had already consulted Prime Minister Tanaka.

Post-war shift

Seigen Tanaka (1906–93), who had served as leader of the Japanese Communist Party while a student at the University of Tokyo in the 1920s, had spent 11 years in prison for violating the Public Order and Police Law. After World War II, his beliefs took a sharp turn to the right and he was able to forge personal relationships with a wide range of individuals of both leftist and rightist persuasions. These ranged from prime ministers to leading businessmen, as well as leaders of student movements.

Seigen had a reputation as being something of an international fixer, having obtained oil concessions in the Middle East and Indonesia, and having formed personal ties with individuals including: Archduke Otto von Habsburg of Austria, the last heir to the Austro-Hungarian Empire; Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping; Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan Al-Nahyan, veteran ruler of the United Arab Emirates; and Kazuo Taoka who headed Japan’s largest underworld syndicate, the Yamaguchi-gumi.

In an attempt to increase crude oil sales to the Japanese market, BP had counted on Seigen Tanaka as a mediator between them and the local oil industry. Beginning in the 1960s, Seigen was involved in negotiating Japan’s participation in BP’s share of the El Bunduq oil field in the waters off Abu Dhabi and Qatar as well as with the Abu Dhabi Marine Areas, Ltd.

Warning ignored

However, Seigen’s reputation in Japan was divided and controversial. While some saw him as a patriot, others labelled him an éminence grise, a powerful, behind-the-scenes string-puller, who had gained massive profits from the deals. In the Diet in the 1970s, an opposition party member asked a question about his commission of several hundred million yen, while the British embassy’s commercial counsellor also suspected Seigen’s credibility.

Nevertheless, BP management—including Chairman Eric Drake—had firm confidence in him, and the British documents suggested that financial gain was not Seigen’s only motive.

On 14 September, 1973, during a visit to London, Seigen sent a memo to the FCO warning of the immediate threat of war in the Middle East and an oil crisis. Based on “dependable information gathered from different sources”, Seigen called for concrete measures by the highest leaders of Japan and Great Britain to cope with it.

But, apparently bewildered, the FCO bureaucrats didn’t take his warning seriously, and a senior official wrote in a memo, “this man is dangerous!”

Only three weeks later, the 1973 Arab-Israeli War erupted and OPEC imposed an oil embargo, triggering a global oil crisis.

Declassified British documents about Prime Minister Kakuei Tanaka in the 1970s shed new light on the role of the enigmatic fixer, the “Tiger of Tokyo”, in the post-war Anglo–Japanese relationship.

BCCJ ACUMEN has two signed copies of this book to give away. To apply, please send an email by 30 November to: publisher@custom-media.com Winners will be picked at random.