Loss clouds promise of literary journey

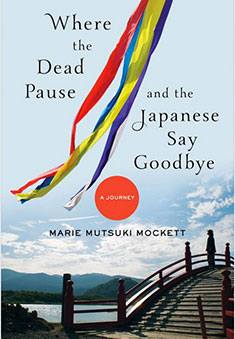

The book under review is in search of itself. It is hard to say exactly why, but it fails to deliver on what it promises. The title is loaded with such promise that the reader is quite rightly drawn to it. Perhaps, being badged as “A Journey” is a clue as to why the book does not ultimately work. Most journeys have a goal, a purpose, a destination.

Yet, the author, Marie Mutsuki Mockett, appears to not have even the beginnings of a map—let alone a compass—to guide her writing beyond a vague connection with the Great East Japan Earthquake and tsunami of March 2011 and a somewhat anxious attempt to capitalise on it.

I so wanted the book to work and there are some tantalising moments that suggest the author is capable of writing something with real impact.

But, unfortunately, finding the core substance in this volume is like taking hold of some of the ghosts of which she writes, real or imagined. Hers is like a voice from an empty room.

US-based Mockett, whose family are the proprietors of a temple in Fukushima Prefecture, ostensibly sets out on a journey aimed at helping her cope with her grief at being unable to bury her grandfather’s remains, in addition to the sudden death of her father.

She appears unable to decide whether her book is a journal, a recounting of history or a cultural guide to Japan. It tries—too hard—to be each of these and thus unfortunately, but not surprisingly, succeeds in being none of them.

At times it is both self-indulgent and patronising, leaving the reader wondering why a firmer editorial hand has not been at work.

To be fair, there are sequences that are engaging, as with the brief history of Buddhism in chapter six. Yet, even here the question has to be: for whom is the author writing?

If one knows nothing at all about Buddhism and its introduction into Japan, it could be considered a reasonable interpretation. However, if the aim is to explain the influence it still has today, it is far too simplistic an attempt.

Meanwhile if the reader has some understanding of the complexities of how Buddhism was founded and developed in Japan, and how it fits in with the indigenous religion, Shintoism, it leaves many questions unanswered. In fact, so much so that it ultimately begs the question: why bother with it?

Mockett’s forays into Japanese history are equally questionable. Again, as a pocket guide to what happened and when, it is perhaps acceptable but no one looking for a serious explanation of the country’s extraordinary legacy will find it expounded here.

Perhaps I am being unfair. Mockett makes no claim to be writing a history; she writes with a great deal of honesty about personal topics. These include her own family’s history, her sense of grief and loss, as well as the hopes she has for her son.

There may truly be a powerful book here, but in the making. The book’s publicists’ blurbs speak of “lyrical meditations” and “cultural insight”. I would argue that this does not yet describe the book.

I hope that Mockett revisits the subject when she has a little more distance from her pain and greater editorial support to guide her.